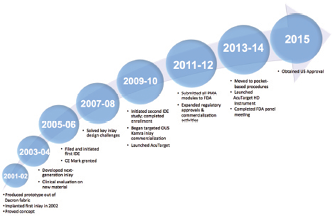

On April 17, 2015, after a decade of research, hundreds of patients tested in clinical trials, six iterations of the product, and volumes of data collected, analyzed, and presented, AcuFocus announced that the FDA had approved the company's flagship product, the Kamra inlay (Figure). The approval represents the first major advance in the surgical correction of presbyopia in more than a decade and serves as a validation of the pioneers who—in the early part of the century—worked to prove the merit of moving forward with a novel design.

ORIGIN

The origin of the Kamra inlay dates back to 2001, when Ed Peterson, an eye care veteran who spent 16 years at CooperVision and another 6 years at Alcon, was working as the vice president of business development at the Innovation Factory, a medical technology incubator in Duluth, Georgia. Mr. Peterson acquired a patent for the small-aperture design, and soon afterward, he and his colleagues developed the first small-aperture corneal inlay prototype. Previous inlays either changed the corneal curvature or the corneal power, whereas the new design used the optical principle of depth of focus.

Mr. Peterson and venture capitalist Bill Link, PhD, of Versant Ventures partnered to advance this new technology. Dr. Link, who has invested in several early-stage ophthalmic companies, recalls being intrigued by the unique optical principal of the new inlay design.

“From an optics standpoint, as a rusty engineer, I was intrigued that it might be something that would be interesting to evaluate,” Dr. Link said in an interview with CRST. “I said to Ed [Peterson], ‘Let's talk with a few experts in optics to validate the optical principal,' which we did. We got encouragement that this might work.”

Versant Ventures provided the initial financing, and AcuFocus was founded in 2001 with the intent of developing and eventually commercializing the new small-aperture design.

One of the first tasks of the newly formed company was to prove the small-aperture concept in a human population in clinical assessment. In 2002, the very first small-aperture devices were implanted by Arturo Chayet, MD, of the Codet Vision Institute in Tijuana, Mexico.

“We knew we had a safe product,” Mr. Peterson told CRST. “However, we still needed to perfect the appropriate thickness, how many tiny holes needed for nutrient flow, and all the remaining precise technical data.”

According to Mr. Peterson, Ramon Naranjo-Tackman, MD, of the APEC Hospital Luis Sanchez in Mexico City was the next physician to step up and help with the trials in Mexico. “We received a great deal of excellent data from this phase,” Mr. Peterson commented.

One of the physicians whom Dr. Link asked to travel to Mexico to assist in the research was Daniel Durrie, MD, director of Durrie Vision in Overland Park, Kansas. Dr. Durrie shared his impressions of the early trial. He first started working with corneal inlays to correct aphakia in 1985.

“I was very impressed with this early, fairly crude prototype,” Dr. Durrie said in an interview with CRST. “Patients were able to improve their near vision, and it seemed to be tolerated very well. The inlay at this time was 35 µm thick and was made out of Dacron mesh. It was too bulky. At that point in time, we didn't know what diameter was needed on the outside of the inlay or the ideal inner diameter. We didn't know the [optimal] depth. We didn't know what surgical techniques to use, but we could tell that the proof of concept was really established.”

Impressed by the early trials, Versant Ventures invested additional capital in the product and advanced the fundamental development work. The inlay underwent a series of changes to its composition and design. The researchers established more effective ways to have the inner and outer diameters increase the depth of focus. Dr. Durrie said much of the early work was on the optical dimensions but that, later, the device went through several changes in material, thickness, and nutrition holes.

SAFETY AND FUNCTIONALITY

The next major step in the development stage came in the fall of 2005: 30 cases performed in Istanbul, Turkey, under the leadership of Ölmer F. Yilmaz, MD, of Beyoglu Eye Training and Research Hospital.

“Dr. Yilmaz was very creative and impactful with his ideas in moving the product forward,” Mr. Peterson said. “All of these patients were looked at very, very carefully. We would spend an entire week there, seeing all the patients, going through all the data, asking all kinds of questions. That's when we figured out the device and what we needed to do to make it better. All of the previous issues we experienced were resolved in Istanbul.”

Mr. Peterson made 29 trips to the city, often accompanied by leading US ophthalmologists such as Marguerite McDonald, MD, Richard Lindstrom, MD, and Jack Holladay, MD. He recalls being so moved by the patients and the work being done there that he decided to have the inlay implanted in his own eye.

“I'm seeing how well the patients are doing, and they were such wonderful people,” Mr. Peterson remarked. “I'm standing there with my reading glasses on taking notes, and I felt guilty about that. If I was going to ask other people to put this device in their eye, then why wasn't I putting it in my own? That very afternoon, I also became a Kamra patient.” Nine years later, the inlay is still in his eye, and Mr. Peterson said that he has J1 near vision and distance visual acuity of 20/15.

“Once we were confident that we had a safe and functional product, we received [the] CE Mark and expanded the clinical trials in many countries,” Mr. Peterson said.

Among the international participants in the trials were Günther Grabner, MD, director of the University Eye Clinic at Paracelsus Medical University in Salzburg, Austria; Matthias J. Maus, MD, medical director of refractive surgery at Augenzentrum Maus+Heiser, Cologne, Germany; Minoru Tomita, MD, PhD, medical director of the Minoru Tomita Eye Clinic Ginza in Tokyo; and Robert Edward Ang, MD, senior consultant, Asian Eye Institute, Makati City, Philippines. Mr. Peterson said the data from the expanded clinical trials led to the company's filing with the FDA.

Figure. A timeline for the Kamra inlay. Abbreviations: IDE, investigational device exemption; OUS, outside the United States; PMA, Premarket Approval Application.

THE FDA APPROVAL PROCESS

In 2005 and 2006, AcuFocus filed and initiated an investigational device exemption with the FDA, paving the way for clinical trials to begin, which started the approval process in the United States. It was at this time that some of the changes were initiated that led to the inlay's current design. The thickness of the device was reduced from 10 to 5 µm. The number of microperforations increased from 1,600 to 8,400 and were arranged in a pattern to allow appropriate nutrient flow and to minimize light scatter. Moreover, corneal pockets were now made at a depth of 200 µm with a femtosecond laser.

“When I came to the company, I was really impressed with the work that that team had done,” said Nicholas Tarantino, OD, chief global clinical research and regulatory affairs officer at AcuFocus, who joined the company in 2013 to help get the Kamra through the FDA approval process. “Over the last 5 years, it was really about optimizing the procedure, because you can have a great product, but the surgical procedure needed to be optimized.”

Dr. Tarantino said, in recent years, the surgical technique involved in implanting the Kamra became more precise, including getting the exact right depth in the cornea and making sure an inflammatory response was not created when dissecting the pocket.

Dr. Tarantino also credited the FDA, calling the agency “a great partner” through the late stages of clinical trials and willing to communicate to AcuFocus what needed to be done to obtain approval.

“The history's a good story,” Dr. Durrie remarked. “A lot of people can say it took a long time and a lot of invested capital money and a lot of patience to get there. It's a story of ophthalmology working with industry, with our patients worldwide, to try to bring a first-in-kind device not only to the US patients but internationally.”

Dr. Link recalls the reaction of his colleagues when the FDA clearance was announced just prior to the annual meeting of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery in San Diego in April 2015.

“We were all fired up,” he said. “That happened at such a good time, but I had underestimated the positive response we were going to get from the surgeons. It was really, really rewarding and encouraging to me that they were very excited to have the Kamra inlay available. It made me realize innovation is hard in the refractive surgery-presbyopia area. I think that the surgeons and the patients are going to benefit a lot.” n