1. The gender gap in ophthalmology is shrinking. What, in your opinion, can this be attributed to?

Lisa Brothers Arbisser, MD:

It’s attributed to both an increase in the number of women in medical school and the prestige and attraction of the ophthalmology specialty. The mix of medicine and surgery, the ability to see all ages and genders of patients (without the need to disrobe), and the low emergency nature of the field makes it particularly attractive and well-suited to women, who often seek a work-life balance that much of the practice of medicine does not afford. The delicate and exacting nature of the surgery is also appealing.

Ashley Brissette, MD, MSc, FRCSC:

Having more female representation in the specialty is one factor. When you can see a representation of yourself succeeding in a certain field, it lets you know that this is a goal you can achieve for yourself as well. Keeping female ophthalmologists prominent in publications, at the podium, and in research is important for recruiting the next generation of female ophthalmologists.

Sumitra S. Khandelwal, MD:

Medicine is a tough field, but ophthalmology allows flexibility. In ophthalmology, you can work part-time or full-time. You can be a primary eye care provider or a specialist and just do surgery. You can be in a group practice, in academia, or in solo private practice. This is helpful for women starting their careers who may want to be in a field where they have many options.

Cynthia Matossian, MD, FACS:

Women are entering medical school at a much higher percentage than in years past. About 50%, if not more, of students entering medical school are female.1 This trend is also reflected in ophthalmology, whereas, decades ago, ophthalmology was male-dominated.

Further, our culture is becoming more accepting of women in most arenas of life. For example, in school, sports have helped equalize the gender gap perception. Boys and girls are growing up with fewer biases. Men and women, even though genetically different in terms of XY and XX chromosomes, are comparable in terms of capability, wisdom, and intelligence. We all are human beings who share similar goals. There is no reason for a gender gap.

Cathleen M. McCabe, MD:

The gender gap has been shrinking for years in response to medical school classes having become more gender-balanced. Although surgical specialties have been slower to close the gap, ophthalmology residency programs specifically have seen a closing of the gap over the past several years. There is a lag between better gender balance in medical school and residency admissions, and this is then reflected in a lag between practicing ophthalmologists and leadership positions. Ophthalmology as a profession, and especially as a surgical specialty, has always been a bit more family- and lifestyle-friendly than some other specialties. For a surgically heavy specialty, we infrequently have after-hour emergencies, and we can create clinic schedules that are more flexible.

Marguerite B. McDonald, MD, FACS:

My view on this is very pragmatic: Now, with more women in ophthalmology than ever before, it is hard to ignore a so-called minority group that is this large. (Read more of Dr. McDonald’s thoughts on challenges faced by women in her accompanying sidebar.)

The Challenges of Yesterday

Lessons learned in a satisfying career in ophthalmology.

By Marguerite B. McDonald, MD, FACS

I was attracted to a life in medicine because my dad was an orthopedic surgeon and the director of the local ER; he clearly took great joy in his work. Dad came home every night with incredible stories, mostly with happy outcomes. Some days, though, he would go straight to the living room, sit in his favorite lounger, and stare silently at his clenched hands for hours. These were the days when mom whispered, “Dad had to tell another set of parents that their son died in a motorcycle accident.”

Ophthalmology interested me because I had significant bilateral vision issues as a child. I was treated successfully, and I saw clearly for the first time when I was 5. Eventually, I decided that I wanted to do for others what had been done for me.

I hesitate to tell stories from my early days in medicine because young women won’t face most of the challenges that I faced—though they will still face some of them. Also, telling these shocking stories makes me seem older than Methuselah, even though they took place not so long ago.

THE PLAYING FIELD

The overall picture is now better for women in medicine, but the playing field is still not flat. I recently read an article about the gender pay gap among general surgeons.1 It was a well-done study with equal numbers of male and female surgeons enrolled. The surgeons had all done similar residency and fellowship training in prestigious programs, they worked the same number of hours each week in the office and in the OR, and they performed the same number of cases. Yet the male surgeons earned significantly more money than the female surgeons. The investigators discovered that most of the cases with high reimbursement potential went to the male surgeons and most of the low-reimbursement cases went to the female surgeons. In their conclusion, the investigators stated that the next goal of their research is to discover why this occurs: Is it that male physicians like to refer the high-reimbursement cases to other male physicians, or do the high-reimbursement cases get referred to the male doctors at the point when the calls come in to the switchboard or front desk staff? I am eager to read their next article.

I do not regret my choice of career in medicine or in my choice of ophthalmology in particular. It has been an honor, a challenge, a privilege, and a joy. Our field changes so quickly—for the better—that one feels the need to catch up after even a 1-week vacation! It is crucial to constantly learn new things, whether it is about drug therapies, surgical techniques, or in-office procedures.

Our specialty requires knowledge, courage, self-confidence, and dedication. We make intraoperative maneuvers that require micron and submicron accuracy, so our hand-eye coordination must be impeccable. Most of us take this responsibility very seriously; we go to bed early the night before surgery and forgo the glass of wine with dinner.

Women have these characteristics, just as men do, but we can sometimes be a bit low on self-confidence and courage. As an ophthalmologist friend of mine said, “If we women have a surgical case that doesn’t go quite the way we planned, we instantly doubt whether we should even be surgeons. My male colleagues are similarly distressed in this situation but manage to shrug it off as a bad day in the OR.”

Courage is a critical ingredient in the secret sauce of success. To quote Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Courage is not the absence of fear, but rather the assessment that something else is more important than fear.”

1. Dossa F, Simpson AN, Sutradhar R, et al. Sex-based disparities in the hourly earnings of surgeons in the fee-for-service system in Ontario, Canada.JAMA Surg. 2019;154(12):1134-1142.

M. Amir Moarefi, MD:

Women leadership in our field is very strong, which I believe helps to narrow the gender gap. If you look at the podium at any major ophthalmology meeting worldwide, you will find that many influential key opinion leaders are women who wow us with their research and their ability to provide excellent care to patients. Women also have a lot of programs supporting them, which might not have existed 20 or even 10 years ago. This certainly is appealing to the next generation of medical students.

Lisa M. Nijm, MD, JD:

In addition to what my colleagues have shared, I believe the closing of the gender gap can also be attributed to greater recognition of our qualified female medical students to promote into ophthalmology. Further, just like in any other field, having prominent role models who are also women encourages more young women to pursue ophthalmology themselves.

Karolinne Maia Rocha, MD, PhD:

More women are graduating medical school now, and men and women are equally intelligent and hardworking. This is allowing us to catch up to men. That’s one factor. But another factor may be having more time. Women are getting married and having kids later in life these days, giving them more opportunity to study and specialize before starting a family.

Arsham Sheybani, MD:

The gender gap started outside of and then penetrated into medicine. As far back as the 1700s, girls’ and boys’ schooling was segregated in the United States. Education for girls focused on preparing them for professions in caretaking, such as nursing and teaching, whereas education for boys focused on preparing them for admission to boys-only town schools.2 It wasn’t until the 1970s, with the passage of Title IX in 1972 and the Women’s Educational Equity Act in 1974, that boys’ and girls’ educational patterns began to follow the same trajectory.

Establishing more equal focus in schooling from the very beginning has helped to shrink the gender gap. In ophthalmology, we’ve just recently started to reap some of the benefits of society’s investing in educating females many years ago.

It wasn’t so long ago that women began entering the medical field. The story of Elizabeth Blackwell is so inspiring. She was the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States and to be listed on the Medical Register of the General Medical Council in the United Kingdom. She created a medical school for women in the late 1860s.3 Since then, women have made huge strides and now represent such a crucial part of medicine. It has taken some time for them to catch up, in terms of numbers, but we’re seeing that now.

Denise M. Visco, MD, MBA:

The shrinking gender gap is attributable to the gains women have made in the dimensions of educational attainment, occupational segregation, and work experience.4 I don’t think that ophthalmology is unique or different from the rest of Main Street; if anything, we are lagging.

O. Bennett Walton IV, MD, MBA:

We’re seeing slow, downstream effects of the early pipeline: Women now represent the majority of medical school attendance.1

My perspective is colored by always having had wonderful colleagues and faculty during training who were both men and women. Were I 10, 20, or 30 years older, my perspective might be different. To quote Warren Buffet, “When I look at what we have accomplished using half our talent for a couple of centuries, and now I think of doubling the talent that is effectively employed—or at least has the chance to be—it makes me very optimistic about this country.”5 The same applies to ophthalmology, which remains intently based upon the quality—both surgical and intellectual—of the doctor.

George O. Waring IV, MD, FACS:

The fact that the number of men and women in ophthalmology residencies is fairly equal right now1 is wonderful, and I think the reasons for this are multifactorial. Academic programs value and promote diversity. However, what this comes down to is the simple fact that women are often more deserving—whether because of their test scores, achievements, interview skills, recommendations, research, or publications. Having served on many resident and fellowship committees, very commonly the majority of the top performers are women. It’s tough to know exactly why that is, but today we rarely if ever even have to say, “Hey, let’s make sure we have an equal gender split.” It tends to work itself out.

It was Margaret Thatcher who said, “If you want something said, ask a man. If you want it done, ask a woman.” I think that sums it up nicely: Women are getting the job done.

Blake K. Williamson, MD, MPH, MS:

The gender roles that might have existed in previous generations are less prevalent now, and appropriately so. More women are considering medicine as a career, and ophthalmology is a specialty that provides a good lifestyle balance so that surgeons can be mothers, too.

2. Even though the number of women in the field of ophthalmology is growing, the percentage of women department chairs, full professors, researchers, speakers, and practice owners is still relatively low. What can female ophthalmologists do to improve this? How about male ophthalmologists?

Dr. Arbisser:

As far as looking at achievements in ophthalmology, I think that has been more difficult for women. Whether that’s history, a glass ceiling that needs to be broken, or the undeniable commitment of time to the surgical aspect of our specialty, something has held us back a little bit. It’s all circular in that the more volume you do, the better surgeon you are, the more you’re important to industry, the more you teach, the more you learn, and the more patients will come to you. That can be challenging for anyone who’s trying to lead a balanced life, which tends to be more women than men, in my experience.

I was able to excel at that challenge at a time when there were very few women in our specialty. This is partly because of the great partnership I have with my husband of nearly 50 years, who saw my talent and helped to promote me. He convinced me I didn’t need to see routine patients all the time or conduct every single postoperative visit, which allowed me to make room in my schedule for more surgery. He was able to put aside hubris, and I was able to step up to the task. Where men still dominate, they have to be sufficiently secure and prescient to step aside and make room for women when appropriate. Women didn’t get the vote in this country on their own! Despite the suffrage movement, success required men voting for it! Today, there are more women who understand how to prioritize their goals, and they are striving to achieve those goals for themselves. But our progress in general still depends on the men—often in charge—making room for us and recognizing this is often to their own advantage.

Dr. Brissette:

Both female and male ophthalmologists need to become sponsors of female ophthalmologists in order to improve the percentages in those leadership categories. Sponsors—in contrast to mentors, who provide guidance and advice—are advocates who promote an individual directly by providing real opportunities for speaking, research, publications, and promotions. (Read more of Dr. Brissette’s thoughts on sponsors and mentors in her accompanying sidebar.)

My Career Path Into Academics

Implicit bias can be a barrier to women, but things are changing for the better.

By Ashley Brissette, MD, MSc, FRCSC

When I started medical school, I didn’t know that I wanted to be an ophthalmologist. At the time, I thought I liked emergency medicine because everything seemed new and exciting. But I am delighted that I stumbled upon this specialty because there is nothing else I would rather be doing than helping people see better.

My ophthalmology residency was at Queens University in Canada, followed by a fellowship at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, where I am now an assistant professor of ophthalmology.

Although I never thought about the gender gap during my early years in training, I recognize now how it played a role in my training. During my clinical rotations in medical school, I realized that I loved surgery. Hearing over and over again that it is difficult to be a woman in surgery, and seeing many fewer female attendings in surgical specialties, I wondered if surgery was the right career path. I think that was the first time I truly understood what it meant to have a gender gap in medicine.

Implicit or unconscious bias does exist. As much as we would like to think we are personally unbiased in medicine, implicit bias affects our understanding in an unconscious manner. I believe that, until we see a balance of women in the field in high leadership positions and on the podium, this bias will continue.

MENTORS AND SPONSORS

I have been incredibly grateful for the many mentors and sponsors throughout my training in ophthalmology, each with different strengths and insights.

It is imperative, however, to understand the distinction between mentorship and sponsorship. A mentor is an individual whom you seek out for support, guidance, and advice on different aspects of your career. A sponsor is an individual who will advocate for opportunities for you and can use his or her network to connect you to career advancement via involvement in research and nonpeer-reviewed publications and who can endorse you for academic advancement.

Sponsorship is especially important for the advancement of women in ophthalmology. Women are still overlooked for speaking engagements, academic promotions, and industry involvement in comparison to our male colleagues. One piece of advice that I received was to ask for opportunities. Let those in positions of leadership know where your interests lie so that, when they are thinking of people to involve, you will come to mind.

When I started my fellowship, I was keen to get involved in research projects in ocular surface disease. I spoke to faculty members and made it known that I would be interested in performing research and submitting papers to conferences. This not only improved my research acumen but also gave me opportunities to speak and present my research to colleagues around the world.

HEADING IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION

Bringing diversity to the table can only further improve the experience for us, our specialty, and our patients. It helps when we continue to promote one another, to seek out opportunities, and to discuss this important topic.

The conversation is changing. We are starting to see our colleagues call out manels (all-male panels). We are seeing successful events for women in ophthalmology, and we have seen the advent of conferences that support women in ophthalmology by, for example, providing child care and other support for attendees (see Creating a Family-Friendly Educational Meeting by Bonnie An Henderson, MD). Although implicit (and, likely, explicit) bias still exists, we continue to head in the right direction of history, and, as we do, the gender gap will continue to shrink.

Creating a Family-Friendly Educational Meeting

A mentor’s focus on his family was an influence on the founding of EnVision Summit.

By Bonnie An Henderson, MD

I had an amazing mentor during medical school, David G. Campbell, MD, a well-respected glaucoma specialist who pioneered the use of laser iridotomy to treat pigmentary glaucoma. The reason he was a great mentor was not because of his academic achievements, however. He was my role model because of his kindness, sincerity, and intellectual curiosity. He had the enthusiasm of a young child on Christmas morning. He was captivated by how the eye functioned. When faced with an ophthalmic unknown, he would delve into investigating his hypothesis with great zeal.

Additionally, Dr. Campbell was one of the first older male physicians I encountered who prioritized his family over his practice. At that time, many male doctors were focused mainly on their jobs, not on children or household matters. Dr. Campbell, by contrast, made family a priority. He even once asked if we could continue a research meeting while he traveled to his daughter’s lacrosse game so he would not miss the starting faceoff. I had even more respect for him after that.

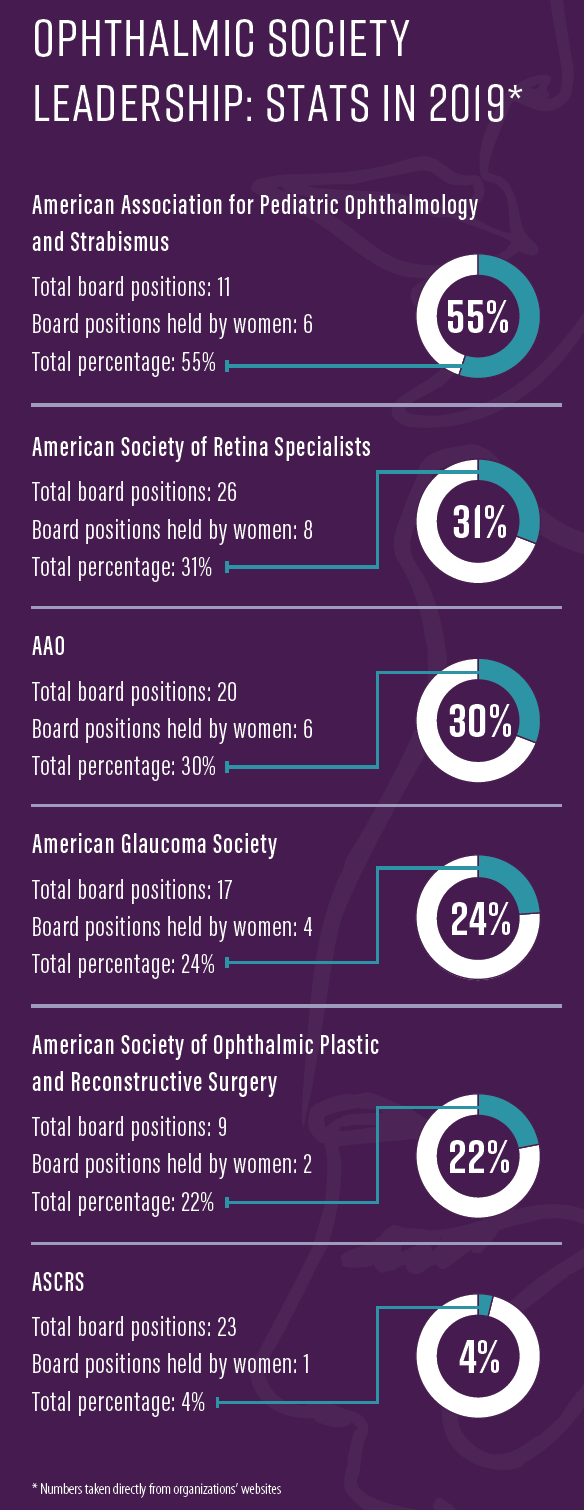

Fast-forward 30 years to 2019. Medical schools have been graduating equal numbers of male and female students for more than 25 years now. Approximately one-third of all practicing ophthalmologists are women. However, the number of women in leadership positions is still well below a third in most ophthalmic organizations (see Ophthalmic Society Leadership), boards, and academic positions.1

UNBALANCE IN BUSINESS

Why is this? In her book about innovators in business, Rosabeth Moss Kanter, the Ernest L. Arbuckle Professor of Business at Harvard Business School, noted that the “male buddy system favors giving CEOs what they want without full, open discussion. Lack of diversity can lead to a kind of crony capitalism in which insiders favor other insiders, surround themselves with people who look and think like them, and rarely hear other points of view. Buddies wink at one another’s indiscretions. They are slow to act when big problems surface, reassuring each other of mutual protection.”2 When corporate boards are homogeneous, she wrote, “it is too easy to fall into groupthink and fail to see or voice alternatives.”

Warren Buffet, in his 2020 annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, expressed his thoughts about this phenomenon. He pointed out that women are underrepresented and still do not have a voice on many corporate boards. Buffet stated that even having one woman on an otherwise all-male board sometimes works against dissent and can instead encourage conformity, as there is pressure on that one woman to conform for fear of being seen as “not a team player” or “not one of the boys.”3

In my own experience serving on boards of medical organizations, I have found this to be true. Most of the time, open board seats are filled by men because they are cronies of the current male board members. I do not believe this occurs because of outward sexism or misogyny. Instead, there is an unconscious desire to add members to your team who look or think the same way. Because new members are usually elected with a vote, if the majority of the voting members are male, they fill open positions with people like them, and this homogeneity continues. It takes a concerted effort to consider people who are different and whom the board members may not know on a personal level but who have the experience, intelligence, and competence to be effective board members.

Similarly, having one token female on an otherwise all-male board can be ineffective and often harmful because the token female is taken to be a spokesperson for her entire sex. This token female must balance the importance of speaking up when she has a differing opinion against the pressure to be agreeable.

FAMILY FRIENDLY

This experience is the reason I founded the EnVision Summit in 2019. This multispecialty ophthalmology meeting offers continuing education and maintenance of certification credits with an innovative approach. Unlike other medical conferences, EnVision Summit fosters a welcoming environment that is open to families.

We understand the challenges of advancing in a career while juggling the needs of a personal life for men and women. That is why, at EnVision Summit, we work to make it easier for attendees to bring their families and for the families to be integrated into the experience. I wanted to create a meeting where the leadership committee was composed of members from diverse backgrounds. By creating a committee of people with different experiences, we hope to foster opportunities for speakers and leaders who may be overlooked at other conferences.

NOT FOR WOMEN ONLY

All ophthalmologists, men and women, are encouraged to attend. In fact, it is imperative that men attend EnVision Summit to experience a conference that is organized differently, with speakers who may not have the name recognition of speakers at other meetings. Seeing how successful this new approach has been, we hope to change the way other meetings are organized in the future.

The success of EnVision Summit is due to the hard work of the program committee, which includes Zaina Al-Mohtaseb, MD; Audina M. Berrocal, MD; Maria H. Berrocal, MD; Malvina B. Eydelman, MD; Angela Maria Fernandez, MD; Gerri Goodman, MD; Mona Kaleem, MD; Carol L. Karp, MD; Judy E. Kim, MD; Geeta A. Lalwani, MD; Wendy Lee, MD, MS; Mildred M.G. Olivier, MD; Eimi A. Rodriguez-Cruz; Liliana Werner MD, PhD; Sonia H. Yoo, MD; and Carrie B. Zaslow, MD. The next EnVision Summit will be held from February 12 to 15, 2021, in Puerto Rico.

1. Parke DW. Gender and leadership. AAO. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/gender-and-leadership. Accessed April 9, 2020.

2. Kanter RM.Think Outside the Building: How Advanced Leaders Can Change the World One Smart Innovation at a Time. New York: Public Affairs Books. 2020.

3. Buffett WE. Berkshire’s performance vs. the S&P 500. CNBC website. https://fm.cnbc.com/applications/cnbc.com/resources/files/2020/02/22/2019ltr.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2020.

Dr. Khandelwal:

Some administrative roles in big academic centers take you away from patients, so I think part of the reason we don’t see as many female ophthalmologists in those roles is that maybe they’re not interested in getting away from patient care. I’m sure many men are like that, too. It is similar with practice ownership. Women can be great owners, but many don’t want to be owners.

The other thing is that ophthalmology still feels like a boys’ club. When you go to administrative meetings, you’re often the only female at the table. A woman can feel like an outsider. If we can get more female ophthalmologists into some of these roles, then I think more will follow.

Also, there is a perception that, if you want to be a department chair, an academic professor, or a researcher, you have to be all in, and this scares some people away. But the reality is, people make it work. Any woman can do it if that’s what she wants to do.

Female representation is slowly increasing, and we’re seeing more institutions creating paths. Baylor, for example, now has a committee to help support getting women into leadership roles. I hope that continues and increases.

Dr. Matossian:

You’re right, the number of women in leadership positions is not proportional to the 50% who are entering medical schools and ophthalmology programs. What we can do is support women coming up the ranks. Become a mentor. Help younger women climb up the ladder in every possible way—from giving advice to writing recommendations, from making introductions to being their sounding board. As the more senior women in ophthalmology, we can help younger women physicians by serving as role models and by motivating them that they, too, can achieve their dreams. (Read Dr. Matossian’s thoughts on her road to opening a private practice in her accompanying sidebar.)

The Road to Opening a Private Practice

Hard work, constant availability to patients, and on-the-job training have taken me far.

By Cynthia Matossian, MD, FACS

Penny wise, pound foolish. Do you know that adage? It came to us many years ago, based on the currency system of Great Britain. The gist of it is, when you make an investment, consider the big picture. Don’t concentrate on counting your pennies if it means in the end you will lose your pounds.

I wish someone had emphasized that lesson to me at one point early in my career. I needed advice from a specialized attorney, but I settled for a less expensive alternative and ended up in an unhappy situation. But it has all come out well in the end. Allow me to explain.

After I completed my ophthalmology training at George Washington University Medical Center, my husband and I looked at different geographical areas where we wanted to settle and start a family. We targeted the geography first and work in those areas second.

We landed in the suburbs of Philadelphia, and I was offered a full-time position in a private practice, which was the type of work I was looking for. My mistake, which is one that a lot of residents and fellows make, was that I did not hire an ophthalmology-specific attorney to look over my contract. At that time, I hired one whom I could afford. Penny wise, pound foolish.

MOVING ON

Be that as it may, that was the situation. I joined the practice, and it soon became clear that it was not the right fit for me. Very little surgery was directed toward me; I ended up working more as a medical ophthalmologist. I left that practice after 1 year. By that time, I felt that I had learned a lot about what to do better, and I decided I wanted to start my own business.

And that is what I did. I moved far enough away that there were no issues with the restrictive covenant from my first employer, and I founded Matossian Eye Associates. To get started, I had to borrow a lot of money. I was young, and it was an era when there weren’t many women in ophthalmology, let alone women starting their own practices. What I was doing was very atypical, and banks don’t like atypical. It took quite a while for me to secure a series of small loans to start the practice.

LEARNING EVERYTHING

Being a practice owner was incredibly hard work. I had to learn new things that were not taught in medical school or residency, including human resources; how to set up accounting systems; how to understand cash flow; how to read a profit and loss statement; how to negotiate with vendors; and how to hire, train, and retain staff members.

I also had to be constantly available to my patients, including evenings and weekends, and take more calls to build the practice and get known in the community. I visited every doctor, every pharmacist, every venue I could think of from where I could potentially get referrals. Over time, that started to pay off. At the beginning, I only had a front desk receptionist and a single ophthalmic assistant, but before long, I was able to hire some doctors and move to a larger location. The rest is history.

LATEST MOVE

About 1 year ago, I sold my practice to a private equity–backed larger entity, Prism Vision Group. For me, this was the right move at the right time. I’m now in the latter part of my career; the sale not only gave me an exit strategy but also provided the comforting knowledge that what I had spent 32 years building will continue under good leadership.

This decision has also made a tremendous difference in what we are experiencing now during the COVID-19 pandemic. Had I still been the sole owner, all the decisions would have fallen on my shoulders. Under the Prism Vision Group umbrella, an extraordinary team of consultants and specialists came into play. Everybody has contributed expertise, and the organization has promulgated almost daily protocols and advice about how to see, prioritize, and space out patients. The burden of stress on me is definitely reduced.

Another way to contribute is to equalize the number of men and women panelists or moderators at meetings. Whenever I am invited to moderate a session or given the opportunity to select physicians for a panel, I deliberately make sure that 50% of the speakers are women.

Dr. McCabe:

As I mentioned previously, part of the imbalance of leadership is due to a lag in changes in the makeup of residency classes. As more gender-equal classes are graduating, men and women will be able to more equally achieve the experiences and durations of practice necessary to reach more senior leadership positions.

Another factor at play is that, early in their careers, women often balance career aspirations with the need to care for young children, which may delay movements to positions of leadership compared with their male colleagues.

Mentorship programs are one key tool for changing the landscape in leadership roles to reflect the makeup of the more gender-balanced cohort of younger ophthalmologists. Female mentors can be great examples for female and male ophthalmologists alike. Male mentors can be equally important, as they set the tone for their career stage–matched colleagues in valuing the elevation of women to positions of leadership. They can also serve as examples of what good leadership and mentorship are for their male counterparts who are earlier in their careers.

Ideally, in the future, the makeup of leadership roles will reflect the body of physicians. The goal must be simply to do our best to elevate all of those who desire to hold leadership positions in our field, participate in research, or be practice owners, teachers, or speakers without distinction based on anything other than merit, hard work, and determination. We are not there yet.

Dr. McDonald:

There are three factors that have helped women in ophthalmology to advance in their careers and positions:

No. 1: Demonstrating an overarchingly superior job performance;

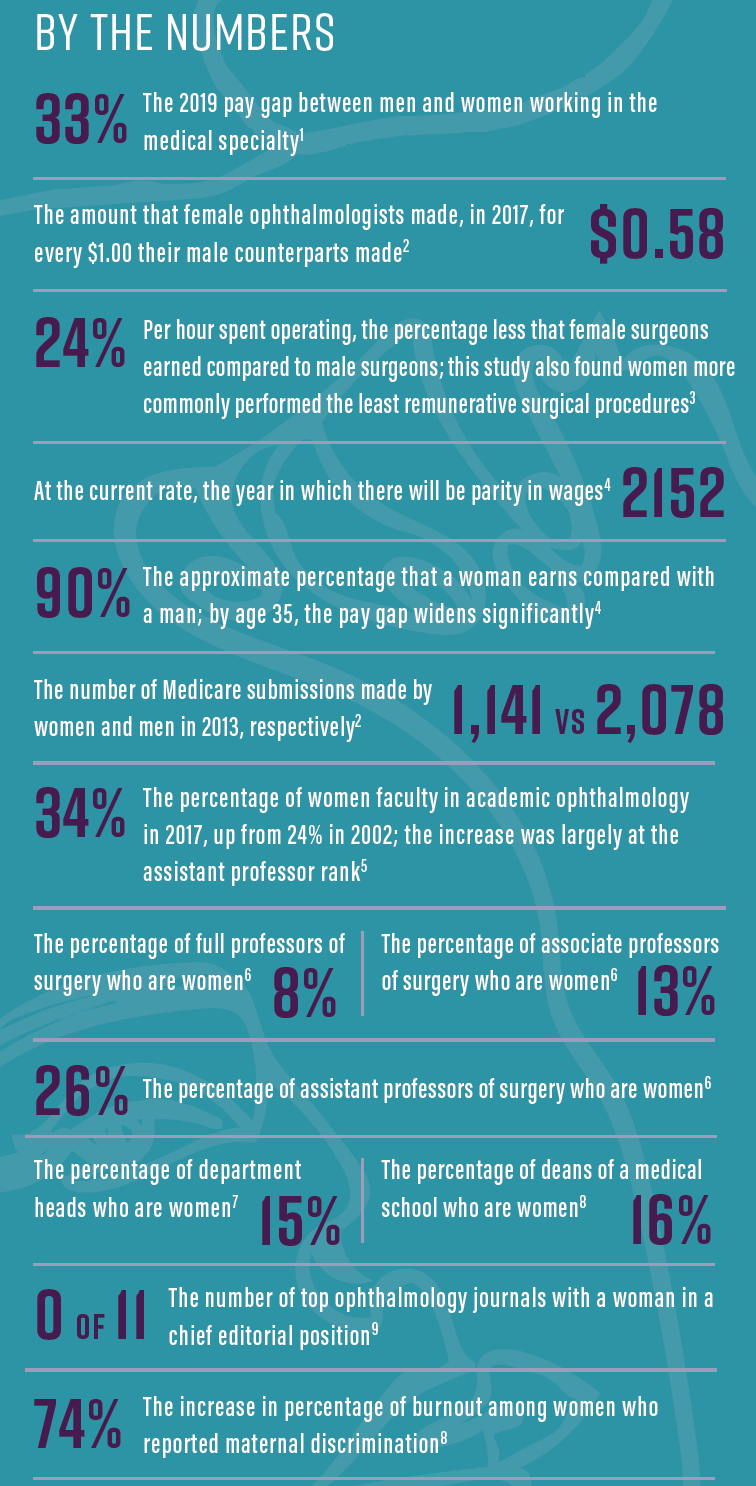

No. 2: Being fully aware of the presence of the gender gap, including the differences between men and women in social, political, and economic attainments (see By the Numbers), as knowing the facts can assist women in their requests for advancement; and

No. 3: Speaking up and letting our wishes be known, including vocalizing what boards you’d like to be on, what title you would like to have, and what talks you would like to give.

1. Ducharme J. The gender pay gap for doctors is getting worse. Here’s what women make compared to men.Time. April 10, 2019. https://time.com/5566602/doctor-pay-gap/. Accessed April 13, 2020.

2. Reddy AK, Bounds GW, Bakri SJ. Differences in clinical activity and Medicare payments for female vs male ophthalmologists.JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(3):205-213.

3. Dossa F, Simpson AN, Sutradhar R, et al. Sex-based disparities in the hourly earnings of surgeons in the fee-for-service system in Ontario, Canada.JAMA Surg. 2019;154(12):1134-1142.

4. Gender Equity Toolkit. Association of Women Surgeons. https://www.womensurgeons.org/page/GenderEquity. Accessed April 13, 2020.

5. Tuli SS. Status of women in academic ophthalmology.J Acad Ophthalmol. 2019;11(2):e59-e64.

6. Why AWS is important. Association of Women Surgeons. https://www.womensurgeons.org/page/WhyAWSisImportant. Accessed April 13, 2020.

7. Year of reckoning for women in science.Lancet. 2018;391(10120):513.

8. ‘A banner year:’ Women leaders established in ophthalmology.Ocular Surgery News. September 29, 2017.

9. Gordon L. Building diversity in medicine and ophthalmology. Paper presented at: Women in Ophthalmology Annual Meeting. August 23, 2019; Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.

Dr. Nijm:

Building on Dr. McDonald’s list, I would say that, in order to rise in the ranks, female ophthalmologists should aspire to achieve two additional goals.

No. 1: Identify professional milestones and find mentors who will support and guide you in reaching that level; and

No. 2: Work to hone your leadership skills so you can succeed when opportunities present themselves.

Female ophthalmologists should embrace their ambition and not shy away from leadership opportunities. Identifying concrete goals, finding mentors who can help you delineate what steps you need to take in your career to achieve those goals, and sharpening your skills along the way can all help to increase the number of women leaders in ophthalmology.

There’s also a lot that our male colleagues can do to help bridge the gap. First and foremost, men can be outstanding mentors. Some of my greatest and closest mentors are male ophthalmologists who recognized talents and skills—not gender—and provided guidance to me on what I should do to move forward in my career. Male ophthalmologists can also sponsor, encourage, and nominate women for talks, awards, committee roles, and boards. In fact, one of the easiest things that men can do is simply politely request a female voice be added to a speaker list, panel, or board when they see one is lacking. Further, sharing salary data and negotiation pearls can help ensure women thrive in these opportunities.

Dr. Rocha:

We now have some amazing organizations, such as Women in Ophthalmology (WIO) and CEDARS/ASPENS, that support women, but I think we are reaching the point where we don’t need women-only groups as much today. I definitely think women are stronger in ophthalmology now; we have a larger voice, and as a result, I don’t see gender as so much of a factor.

It’s important for women to join groups and organizations of all types, not only WIO and CEDARS/ASPENS, but also like the AAO and the Refractive Surgery Alliance. These organizations have great memberships that can help all physicians at all levels. Clinically and resource-wise, these groups are wonderful.

Dr. Visco:

Women are on par with men in getting medical and legal degrees, yet, across the board, men are far more likely to receive the most prestigious and highest-paying leadership rolls.6

Ophthalmology is unfortunately no different. A recent study found that female residents performed fewer cataract operations and total procedures than male residents.7 Ironically, the men who took paternity leave performed a mean 27.5 more cataract surgeries than those who did not take any leave. One good note was that the female residents’ numbers were neither enhanced nor penalized for taking maternity leave.

As the Association of Women Surgeons has stated, for the female ophthalmologist, “battling workplace bias requires deliberate strategies, including learning to say no, getting comfortable talking about uncomfortable topics, and helping others behind you.”8

There are things we can do. When you see bias occurring, discreetly make the individual aware of the biased behavior. Actively manage how others view you by learning and practicing leadership skills. Nurture relationships with other female mentors and support other women in senior roles. Finally, understand your workplace policies on discrimination and your rights.

My advice to male colleagues is to do your best in considering how you make decisions and choices. Gender bias is cultural, and we all should be mindful of our language and behaviors. Intervene when a female colleague is spoken over or demeaned. Make a point of showing your male colleagues the value of female contributors and promote a culture of gender-neutral meritocracy.

3. What are some ways that women can hone their effective leadership skills in the hope of advancing in rank within their practice or academic institution?

Dr. Arbisser:

There are many types of leadership, and leadership in surgery and leadership in organized medicine require different skills and tasks. Does a woman have to be president of an organization in order to be a leader? Not necessarily. It could be that a woman is making sure that people are doing the highest-quality work, and that is being a leader, too.

It might take our redefining what leadership can be in order for us to capture more of those leadership roles on the way to achieving our highest goals. Speaking up and getting noticed for quality is fulfilling; unfairly unrequited achievement is a stain upon our profession—whether that manifests as gender, religious, or racial bias.

Dr. Brissette:

Reviewing what is required to achieve the next level of leadership within your institution is helpful. Most institutions have clear guidelines for promotion, and some even offer workshops on promotion and career advancement; I would recommend pursuing these if this is of interest. For instance, I completed a leadership course called Leadership in Academic Medicine, and it was a big eye-opener about the process for faculty development and promotions at our institution.

Also, it’s important to advocate for yourself and to let your superiors know that you are interested in promotion. Often, they are looking for individuals to get involved in leadership or other activities. By letting them know you are interested in these opportunities, you gain a higher chance of being considered.

Dr. Khandelwal:

You don’t necessarily have to have female mentors to learn how to be an effective practitioner. It’s great to have leaders who are women to learn from, but it’s also great to have men to learn from. It’s also important to realize that you can have many mentors in different aspects of practice and life.

Women in leadership and mentorship roles must be careful that we’re not our own worst enemies—that our attitude is to lift each other up and not to say, “It was hard for us to get here, and it should be just as hard for the next generation.”

Dr. Matossian:

Women have to let industry know that they are interested in participating in leadership roles—industry cannot read people’s minds. Being vocal and expressing a desire to undertake a bigger role go a long way. Industry likes to work with physicians who deliver what they promise in an organized and timely fashion. Qualities such as tardiness and unpreparedness are not tolerated. Then there are online courses and mentorship programs, for instance through the CEDARS/ASPENS Society. Women can take advantage of the coursework on public speaking to become more effective communicators. WIO also offers these during its annual summer meeting.

Dr. McCabe:

Women can seek out opportunities to refine their speaking, networking, and leadership skills. Mentorship and leadership programs put on by organizations such as the AAO or sponsored by universities are great opportunities for women at any stage of their careers. For instance, in the fall I will be attending Harvard Medical School’s (HMS’s) Career Advancement and Leadership Skills for Women in Healthcare.

Dr. McDonald:

The best piece of advice I have to offer is to go above and beyond what people expect. Volunteer to take on more responsibilities, give more lectures to the residents than required, and ask to join teams and boards.

Dr. Nijm:

Several people have mentioned WIO. One of our primary goals in WIO is to help women sharpen the intangible skills that are needed to be successful in practice. Those skills include things such as improving communication, negotiation, marketing yourself, and preparing an elevator pitch. (Read more about Dr. Nijm’s involvement with WIO in her accompanying sidebar.) Focusing on how to most effectively highlight your achievements and being proud of them are important in this regard, as women often are not as good at self-promotion or don’t have as much confidence in self-promoting their skill sets as men do.

The Benefits of a Dual Focus

Serving patients and colleagues inside and outside the office.

By Lisa M. Nijm, MD, JD

I strongly believe that, for physicians to truly care for their patients, we need to serve as their advocates both inside and outside the office. With that in mind, I chose to enroll in a dual-degree MD/JD program that is geared toward training physicians who believe a legal education will augment their primary career goals in medicine. I find that to be true also in serving my colleagues in medicine. Recently, I have applied the principles I learned in my new role as the first CEO of Women in Ophthalmology (WIO).

I fell in love with ophthalmology during my second year of medical school, after my own routine examination with cornea specialist Peter T. Brazis III, MD, led to the opportunity to spend time observing him at his practice. On my first day, I watched Dr. Brazis perform corneal transplants and cataract surgery. On my second day, I went to patients’ follow-up appointments and heard them speak about how their lives had been transformed by the surgery. I was hooked.

I fell further in love with cornea during my ophthalmology residency, working with cornea giants such as Elmer Y. Tu, MD; Joel Sugar, MD; and Dimitri Azar, MD, MBA. I was motivated by the close relationships one develops with patients and the detailed corneal procedures that can greatly improve a patient’s quality of life. After a corneal and refractive fellowship with Mark J. Mannis, MD, and Ivan R. Schwab, MD, FACS, I returned home to open my private practice in the western suburbs of Chicago and serve on faculty at the University of Illinois Eye and Ear Infirmary. This is where I flourish; I can now deliver patient care in the way I see best.

EMPOWERING WOMEN, IMPROVING PATIENT CARE

Most recently, I have taken on a separate but important role as the CEO of WIO. I like to think that the two are related: By empowering other women, we can unite to improve patient care. My involvement with WIO was sparked by my role in reinvigorating the Women Ophthalmologists of the Windy City (WOW) group. I started networking and creating events that addressed the topics that I, as a female ophthalmologist and practice CEO, thought the women in WOW could help each other with. My work with WOW did not go unnoticed, and I was soon elected to the WIO board. Within 6 months, I was asked to chair the annual meeting.

By applying a similar philosophy to the one I used for WOW, I helped transform the WIO national meeting into a large scientific convention focused on continuing medical education, mastering of surgical skills, and leadership growth workshops. I helped to organize sessions that targeted the intangible skills needed for success in ophthalmology. The size of the meeting doubled the year I chaired it, and subsequently the board elected me president. During my 1.5-year term, I continued to work with the board to improve the fundamental structure of the organization and the benefits and opportunities we were able to offer our members. Last fall, in evaluating the momentum and size of WIO’s growth, the board of directors made a strategic decision to create a CEO position, and I was selected from a pool of candidates to fill that new role.

Overall, being involved with WIO has helped me to further focus on advocating for patients and for my colleagues. One of the greatest benefits is the opportunity to interact with so many dynamic and amazing women leaders from around the world. I’ve been fortunate to interact with, teach, learn, and form lasting friendships with some of the greatest female surgeons in our specialty. Not only has WIO given me the opportunity to grow as a leader, but it also has extended the opportunities I have to work with others in improving patient care and serving as an advocate in our profession.

Dr. Rocha:

Women need to be confident. We’re equally as smart as men, and we just need to resist being denigrated and to stay prepared. For example, for leadership in a private practice, maybe a female ophthalmologist should complete an MBA to make sure she’s ready for that. You need to prepare and educate yourself, go to meetings, and take courses.

Dr. Visco:

Leadership skills can be learned, and lateral leadership—the ability to influence others without formal authority—is extremely important for anyone wishing to advance his or her rank within an organization. Harvard Business Review recommends honing four key skills: networking, constructive persuasion, consultation, and coalition building.9 Cultivate a broad web of relationships based on mutual respect and ideas, learn how to negotiate with a win-win strategy, take time to visit with stakeholders and show interest in their opinions, and, finally, earn advocates who will support and stand by you. Another key point is that leadership learning, as all learning, should be lifelong. I am looking forward to attending the HMS’s Women’s Leadership Conference with Dr. McCabe this fall.

4. Are there certain perceptions and behaviors present in ophthalmology that contribute to the gender gap? What can be done to change these?

Dr. Arbisser:

Ophthalmology has a history of having an old boys’ club mentality, and, unless you aggressively barge your way in, you can be overwhelmed by the unfairness of it all. I was never invited to the resident’s poker game with the chairman. As long as there’s still that mentality, the gender gap will continue to some degree. Unless you’re able to cope with that and be a little more aggressive and demanding in other ways, it’s hard to overcome.

When the mix involves having children, our partners have to pull their weight and break out of that old paradigm that raising children is women’s work. It’s a juggling act, and there is always at least one ball in the air we are praying to catch.

Dr. Brissette:

There are always biases, including implicit ones. As much as we would like to think these don’t exist, they do. It’s difficult to change a practice’s culture, but, by continuing to discuss this important topic, we can slowly remove these biases over time.

Dr. Khandelwal:

Women who decide to take some time away to be with their babies can be penalized in the academic rank process because of that. If they’ve taken a step back, it’s worked against them.

But the reality is that women are doing a very important job in this world by having babies and taking care of their children. So we have to have a better system in institutions, where there is a path to leadership without having to be full-time all the time. Some institutions are working on ways to do that.

Dr. Matossian:

Pregnancy and maternity leave are a reality for many women. There is more acceptance of women’s stepping away from their career paths for short intervals of time to have families. Most women return to work with the same serious intent that they had before having a baby, provided they have adequate childcare and support at home.

Some women choose different paths in order to find their work-life-family balance, such as part-time work, medical ophthalmology with discontinuation of surgery, or leaving private practice for industry positions.

Our male colleagues have become more understanding and supportive of maternity leave and realize that, just because somebody is out for a number of months, it does not make her a lesser ophthalmologist or less committed to her career than she was before she had a baby.

There are many demands that women with children have to juggle, such as childcare, breastfeeding, sports activities, and school vacations, to list a few. Flexibility and planning ahead are key.

Dr. McCabe:

Historically, surgical specialties have been dominated by strong male leadership, sometimes in the form of somewhat closed networks and circles of influence. This has been the norm in ophthalmology as well. Also, ophthalmology is a competitive field, attracting the type of personality that desires to always be in control and at the top of their game. To stand out, it can be important to put yourself forward, be persistent, and make your interest in advancement known.

We need to encourage confidence and assertive behavior from women in training and throughout their careers. Having strong, more senior leaders encourage these characteristics in trainees and younger partners is important.

Dr. McDonald:

There is still the perception that women with children, especially young children, are not able to take on extra tasks or responsibilities to advance their careers. This is not true. Female ophthalmologists who select supportive mates willing to make lifestyle adjustments so that their wives can advance their careers can certainly do just that.

In the past, many male doctors married nurses. This still occurs, of course, but a significant percentage of young male doctors now marry a female classmate. The relationship, while romantic, is also a true professional partnership, mutually supportive from the very beginning of the marriage.

Dr. Moarefi:

Perceptions exist that contribute to the gender gap. As long as there are differences—whether they be differences in gender, in ethnicity, in age—we must navigate ways to provide equality. We’re all colleagues; we all have the same mission and the same goals in terms of patient care. I think medicine is experiencing a paradigm shift toward a more compassionate patient-centric model, and maybe that is because more women are entering the field.

Dr. Nijm:

Ophthalmology has been a male-dominated field for quite some time. This has led to implicit bias more than anything else. Unconsciously, colleagues may have gotten so used to seeing all-male panels, editorial boards, clinical trial investigators, or academic faculty that they might not realize the lack of diversity present.

Respectfully drawing attention to and recognizing that there are brilliant and highly accomplished female ophthalmologists who can excel in all these roles will help to make sure that they’re included and that they have a voice. This will, over time, help diversify who is speaking on the podium.

Dr. Sheybani:

Today, women can be handicapped by the inherent and sometimes subconscious bias of male-dominated leadership teams that are in charge of selecting the next round of leadership.

Because leadership roles are historically dominated by men, it can be really hard for women to break through, and that can lend itself to a gap in pay. We all hear anecdotal examples where a man and a woman get hired around the same time and the starting salary for the woman’s position is lower (see By the Numbers).

The women who are in leadership positions deserve to be in those roles, and over time we should start to see more women at the helm in various roles. If we were to have the same conversation 20 to 25 years from now, it would be, I hope, an entirely different landscape—one that has a more equal number of women in leadership positions.

Dr. Visco:

I have encountered the same gender biases as a biology student, a bookkeeper, and a pharmacy technician as I encounter in ophthalmology. I will say that, today, the bias is much less and more subtle. The clearest way for women to become adept at overcoming bias is to practice whenever and wherever it’s encountered and as often as possible. In doing so, we hone our leadership talents and prepare for a bright future. A wise women once told me, “It can’t be that difficult if men do it all the time.” The change will come with time and with the development of more women in leadership roles.

Dr. Walton:

I don’t have knowledge of ophthalmology-specific data, but a physician survey article in JAMA Network Open highlighted some interesting trends that likely have a negative effect upon the career outlook of women who are interested in growing in the leadership ranks of academia or in partnership-level private practice positions. Over a period of 6 years, almost 75% of women physicians reported reducing work hours to part-time or considering part-time work, as opposed to approximately 25% of men.10 In any area of statistics, misapplying broader trends to individuals is unwise and statistically lazy. There are always additional details to add to the analysis of individuals. Misapplying these statistics can be harmful not only to the female ophthalmologist but also to the practice or department for possibly overlooking talent.

Dr. Waring:

Just because the number of women entering the field of ophthalmology is nearly equal to that of men1 does not mean that there’s not still work to be done. There are lingering potential inequalities in surgical opportunity. According to a recent study of case logs from 24 US ophthalmology residency programs from July 2005 to June 2017, female residents performed 7.8 to 22.2 fewer cataract procedures and 36 to 80.2 fewer total procedures.7

So the questions are: Why? And what can be done to ensure that future opportunities are truly equal, starting before individuals enter posttraining opportunities?

What a lot of this comes down to is that women tend to make sacrifices for their families more often than men do. If a woman starts her family during residency, that certainly can have an impact on, for example, case volume.

5. What is the role of mentorship in a woman’s career journey? Spanning your career, which women have you looked up to? How have they influenced how you practice?

Dr. Arbisser:

Mentorship is a crucial part of everybody’s career journey, so I don’t know that it’s a gender issue. A mentor must be selfless, and it is therefore beneficial to have more than one mentor—it’s simply too much to ask one person to be great at what he or she does and be a full-time mentor to one or more people.

My mentors were my career mother and grandmother as well as my physician father and pediatric ophthalmologist husband, Amir. (Read more of Dr. Arbisser’s thoughts on mentorship in family in her accompanying sidebar.) In ophthalmology, when I was in medical school, John C. Nelson, MD, showed me the ropes, helping to cement my decision to enter the specialty. I then benefited from many surgeons, especially Howard V. Gimbel, MD; Randall J. Olsen, MD; and Steve Charles, MD, FACS, FICS. I also appreciate many industry representatives who recognized my talent and encouraged my ongoing curiosity and desire to be patient-centric.

Three Generations of Career Women and Counting

Why mentorship comes in many shapes, and how to make the most of an insight.

By Lisa Brothers Arbisser, MD

I have a unique perspective on mixing family and profession. My grandmother was a lawyer, and my mother was the psychologist, television personality, and columnist Dr. Joyce Brothers. It is pretty unusual to have three generations—and now four, including my son’s wife (daughter-in-love) who is a cantor and who with my son is raising our three grandchildren—of professional women. I had a head start in understanding the nuances of work-life balance, and, in every sense of the word, my mother and my grandmother were my very first mentors. They shared with me their knowledge, experiences, and advice—not about the profession of ophthalmology but rather about how to be a respected and successful professional and how to find the right balance in life between work and home.

Mentorship took another shape when I entered ophthalmology. I was only the second female resident ever to be accepted to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Iowa, and, at the time that I started practicing, very few of my colleagues were women. Some of the mentors I had—mostly men—were more virtual mentors in that I watched their surgeries but did not have a lot of one-on-one interactions with them.

But also, in those early days of my career, I was rather aggressive. Ophthalmic companies would invite me to join panel discussions, but some of my male colleagues refused to work with me. At one point, someone on the industry side approached me and offered me public speaking coaching so that I would come across as less aggressive. I could have taken that as a huge insult, but I decided to accept the offer. I really do believe that, if I had been a man, people would have considered me to be assertive, not aggressive (see Stereotypes and Double Standards in the Workplace).

That experience helped me to learn that one should not be wounded by small slights. Instead of being insulted by the offer, I took it as a well-meaning hint. It’s easy to be oversensitive about things, but taking a step back and looking at the big picture can sometimes be helpful and educational. Frankly, those individuals—mentors of a sort—helped me to become better at expressing my viewpoints more gently and constructively. It turned out to be useful advice in my career.

Now that I am retired from patient care, mentorship has taken a different shape: I am the mentor. One way that I try to stay both current and useful is by traveling to other ORs and watching my colleagues’ surgeries. That type of direct mentorship was not available to me when I was early in my career. I used to go to other people’s ORs, but they never came to mine. I hope to continue mentoring future generations of ophthalmologists for years to come.

Stereotypes and Double Standards in the Workplace

A Man Is…

- Assertive

- Direct

- Commanding

- Strong/Powerful

A Woman Is…

- Aggressive

- Shrill

- Pushy

- Domineering

Adapted from: Barriers and bias. American Association of University Women. https://www.aauw.org/app/uploads/2020/03/Barriers_and_Bias_summary.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2020.

Dr. Brissette:

The women who come to mind are those who modeled what I hoped to achieve in my future career. There are many female ophthalmologists I have trained with whom I would say I looked up to and still do to this day. Each of my mentors has provided me with guidance, whether clinical, surgical, research-related, or even personal.

Dr. Khandelwal:

The most important woman to whom I look up is my mother. She’s a physician who had a busy practice when I was growing up but who still managed to create a schedule that allowed her to attend my dance classes and other activities. I don’t know how she did it, but she did. And then she got her MBA when I was in middle school, and now she balances her clinical practice with her medical director role. She’s been a huge influence on my life.

When I’m having issues with balancing it all, she gives me simple, straightforward advice. She’s the one who gave me the best advice: If there’s something you can outsource, then do it, because you can’t outsource being a good mom or being a good wife or being a good physician. That’s an important lesson. (Read more of Dr. Khandelwal’s thoughts on work-life balance in her accompanying sidebar.)

Achieving Work-Life Balance With Young Children

By Sumitra S. Khandelwal, MD

How can busy clinicians and academicians with young families achieve work-life balance in ophthalmology? I’m not sure I have all the answers to that question, but I can offer some perspective from my experience.

I’m an associate professor of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine and Cullen Eye Institute in Houston, where I specialize in cornea, cataract, and refractive surgery. I also train residents and cornea fellows at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and serve as the medical director for the Lions Eye Bank of Texas. In addition to those duties, I am active in ASCRS leadership, where I have served on several committees.

On the home front, I have three children under the age of 5 (including a newborn) and a wonderful husband. The catch is he frequently travels for work, meaning a lot of the life side of that work-life balance falls on me.

GET HELP AND REALIGN

How do I do it? One key is that I have great help. I have this philosophy, which I learned from my physician mother: If I can get someone to help with things like cooking, cleaning, and laundry, then I can focus on the thing I enjoy doing, which is being with my children and husband. (The same philosophy applies to the workplace, by the way. If you can delegate tasks you don’t need to do, best to delegate!)

Another thing that has helped is adopting a mentality of living in the moment. In the past, I’d always be stressing out about what I had to do next. On a nice evening at home with the kids, I’d be thinking about what I’d have to do tomorrow. Or I’d be at work and worrying about when I was going to pick up my kids and what we were going to do that weekend.

To avoid this, I now try to realign myself by reminding myself to be in the moment. So when I’m at the park with my kids, instead of being on my cellphone checking email, I really try to take it all in and enjoy that time. And when I’m at work, I focus on work and being as efficient as possible without stressing about what is going on at home.

I feel that this has changed my whole outlook on life. It also makes each moment just a little bit more important.

DOING IT ALL

There’s no amount of money or credit at work that can make up for missed moments in my kids’ lives. As a result, I decline opportunities now, something that I found difficult to do before. I block clinic for personal conflicts ahead of time, rather than try to rush at the last minute. I found, if I didn’t block more time than needed, I was racing for a flight or event and had more potential to miss events.

It is also vital to realize that you don’t have to be perfect at everything. This is difficult for anyone with a type A personality. I have learned that I don’t have to be the perfect mom, the house doesn’t have to be in perfect order when company comes, and I don’t have to always be the perfect hostess.

LETTING GO

So—three kids, a busy private practice, teaching, research—no problem, right? In the end, there are some things in life that have to give. I don’t follow the news very much. I don’t keep up with social media. TV shows are limited to streaming ones I can watch late at night, and even then I usually fall asleep. I used to spend 10 minutes getting warmed up at the laptop before starting my real tasks. Now I jump right in.

But missing those things is worth it because it allows me to spend time with my family and friends. I have several female colleagues with children, and we make it a point to go to each other’s kids’ birthdays and events and to spend time together. It’s great to be able to interact with other women who have similar struggles and lifestyles and to enjoy the time together—and to let it go together.

Dr. Matossian:

The women I’ve looked up to were not necessarily in ophthalmology. My mom, an incredibly hard worker who was able to manage multiple children, a career, and a household yet made time to be a fantastic mother, has always been a role model for me. Many of the skills I learned are from her.

Then in ophthalmology, I looked at what everybody was doing and tried to do the best that I could. I did not view them as male versus female role models. I emulated the folks I admired and tried to work with them to continually learn from what they had to offer.

Dr. McCabe:

Mentorship is key. The best mentors are those who help to shape your journey and provide not only opportunities for advancement but a vision of the path to get there. Mentors should be a resource for problem-solving and an inspiration for achievement. At the very least, we can look to mentors as examples to emulate—someone whose path we can see ourselves following.

I had the fortune of working with Carol L. Shields, MD, on a research project early in my residency. She was extremely kind and encouraging, and I could not help but admire her knowledge, accomplishments, and prolific output—all while having a large family (seven children!) and a long and happy marriage. There are many other examples from my time at Bascom Palmer, including Mary Lou Lewis, MD; Hilda Capo, MD; and Janet L. Davis, MD, among others. Also, Dr. Arbisser, Dr. McDonald, and other women who took on leadership roles at times when there were few women in those positions have shown us how to be assertive, knowledgeable, and at the top of our games throughout long and successful careers while still maintaining individuality.

Dr. McDonald:

Mentors are important in anyone’s career. I was lucky enough to have a strong mentor for about 3 years, but my mentor was male. There were few female ophthalmologists when I started my career.

Dr. Moarefi:

Some of my biggest heroes in the field of ophthalmology are women who are not only excellent clinicians but also incredible surgeons. In particular, Neda Shamie, MD; Marjan Farid, MD; and Natalie A. Afshari, MD, FACS, are three women I have worked or interacted with, whether through research, rotation, or other functions, who have inspired me to be a better surgeon and clinician.

Women have a different perspective in terms of how they approach eye care. They have a special ability to be extremely delicate, which is important in ophthalmology. Their instruction and knowledge can benefit our entire field and specialty. Women have a lot to offer as mentors, not only functionally but also emotionally. The women mentors with whom I have come in contact have a profound sense of compassion in terms of how they do surgery, how they take care of patients, and even how they approach the business aspect of practice.

Dr. Nijm:

Mentors are extremely important and can help provide guidance toward achieving a leadership goal. Some people are interested in doing research, some in speaking opportunities, and others in practice management. Whatever your leadership goals are, it’s inspiring to have somebody to emulate along the way and to turn to for advice when there are bumps in the road, which most certainly there will be.

Tamara Fountain, MD, and Ruth D. Williams, MD, are two women who I was fortunate enough to meet early in my ophthalmology training and who have been influential for me. They are both incredible leaders within ophthalmology; compassionate clinicians; and strong voices for patients, colleagues, and the profession of ophthalmology.

Dr. Rocha:

Having a mentor at your institution, one of your professors during residency or fellowship, as someone you trust is vital. Remember that these relationships will last forever. (Read more of Dr. Rocha’s thoughts on mentorship in her accompanying sidebar.)

Making the Most of Mentorship

Passing your knowledge to other generations is important.

By Karolinne Maia Rocha, MD, PhD

I did my residency and fellowship in Brazil, where there are some amazing surgeons in the field of ophthalmology. During my cornea and refractive surgery fellowship there, I remember the help I received from all my mentors. I still see them and communicate with them now, 20 years later, connecting to discuss our projects and studies.

But now, I’m also serving as a mentor for students in Brazil and in the United States. I am able to do this because I kept up that connection with my mentors. This continuity, this ability to pass knowledge between generations, is one of the reasons why mentorship is so important.

When I came to the United States, I accepted a position at the Cole Eye Institute of the Cleveland Clinic, where I worked with Ronald R. Krueger, MD. He is amazing in so many aspects—clinician, scientist, speaker, and the director of refractive surgery at the institute. When he was my mentor, I was able to observe him and feel as if, one day, I could be like him. It takes a lot of dedication and many years of learning, going to conferences, and investing time, but it is possible to achieve.

FIND SOMEONE YOU TRUST

That’s why, when choosing a mentor, it is important to find someone you trust, someone you know you can call on for help. You need to have a really great relationship with your mentor. It doesn’t have to be a female mentor, but it does have to be someone who can not only teach you clinical and surgical skills but can also give advice about the direction of your career. Do you want to be an academic researcher, a university professor, a private practice surgeon, or in a more administrative position like director or even chairperson? The mentor should be able to support you in all these possibilities.

There are many paths you can take, but you can only get there if you know where you’re going. Do a little research. I truly believe women can do anything they want, but knowing what you want is an important first step. Then let your mentor or mentors know—this is want I want, this is path I want to take—so that they can help facilitate those choices.

Dr. Sheybani:

Sharon Wahl, MEd, CLS, has undoubtedly been my biggest influence and mentor. She’s now a scientist emeritus at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). At the time I worked with her, she was employed in the NIH’s oral infection and immunity branch in the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. She is extremely sharp and a stellar leader, which drew me to working with her over a period of several years. I annoyed her no end until I finally got a job there, and she taught me so much about working alongside the people whom you lead. She taught me how to be fair but tough, how to expect the world of them but not ridicule them.

I never even thought of her as a female leader. I just always looked up to her as a person. I really owe my successes to her in some ways. She was always encouraging, but she would never let anything slide.

I don’t think much about the gender of a person, but I do have two other bad-ass women role models in my life. My wife, Elizabeth Fowler Sheybani, MD, is from rural Missouri, the only physician in her family, and she had to work extremely hard to get where she is today as a pediatric radiologist. And my sister is a rock star doctor who balances her home life with her work—and works harder than me and my three brothers, all of whom are also physicians.

Being surrounded by strong women in medicine, it is inspiring to see them shatter the glass ceiling.

Dr. Visco:

Mentoring is a long-term relationship that focuses on the growth and development of the mentee. Mentoring is not coaching, which is also important, but rather it involves a finite relationship targeted on strengthening or eliminating a specific behavior. Mentors are very personal and help us see a destination without giving us specific instructions on the path to take. Coaches, on the other hand, tell us how to do things. I have had both mentors and coaches. Women also have role models where there is no personal relationship per se, but the role model has served to inspire us by breaking some glass ceilings.

I have many long-term and meaningful relationships inside and outside of ophthalmology with both women and men who have supported me as mentors, coaches, or role models. To begin naming them would risk forgetting someone. Everything I am and everything I have today are a compilation of my own thoughts and desires and the thoughts and desires of everyone who has influenced me. Basically, everything you see now bears some evidence of their influence.

Dr. Walton:

I’ve always looked up to mentors who desire great things for their patients, treat patients with warmth and respect, and are skilled surgeons. These qualities are not gender-specific, and I have seen many wonderful and a few poor examples in both sexes. Reflecting on this question leads me to believe that I might have missed the opportunity to recognize a different dimension of greatness among female mentors who had overcome additional barriers.

Dr. Waring:

There are many influential women in ophthalmology, but there are two worth mentioning specifically. Dr. McDonald has shown all of us that, regardless of gender, you can be a trailblazer. Dr. McDonald and her husband, Stephen D. Klyce, PhD, FARVO, are a wonderful example of how a husband and wife can support each other in the spirits of science, education, and innovation and most important, on a personal level.

The second is, of course, my wife, Karolinne (Dr. Rocha), who not only is selfless but also fearless in the OR and in ophthalmology and research. She’s literally rebuilding and fixing eyes that nobody else, including men, would touch. But, most important, she’s an amazing mom who somehow manages to be home at 5 pm to be with her children.

Dr. Williamson:

Two of the women I look up to in my personal life are my sister and my wife. My sister, Shelly Williamson Esnard, PA-C, balances running a large, multilocation cosmetic surgery practice with running a household and raising three kids. My wife, Nicole, who made her vision of starting a boutique fitness revolution in our home town a reality, is truly inspiring. She was able to achieve this while being a full-time mom and taking care of four boys: Forrester (8 months), Rains (18 months), Waylon (5 years), and me—the ultimate kid at heart! She often states that I’m by far the toughest child.

In my professional life, there are simply too many women who have influenced me to list them all. From my training at Tulane, I’ll always remember Candace C. Collins, MD, for walking me through my first few LASIK cases—and also for tolerating my relentless approach to putting as many cataract cases on the schedule as possible.

Currently, as peers and colleagues, I love collaborating with Elizabeth Yeu, MD; Zaina Al-Mohtaseb, MD; Julie Schallhorn, MD, MS; and Dr. Brissette on the physician side and Erin Powers on the industry side. And as far as women who have been mentors to me, although I know there have been many others, I must mention Sheri Rowen, MD; P. Dee G. Stephenson, MD, FACS; and Dr. McCabe to name just a few who I feel have gone out of their way to help me.

What has drawn me to these women in particular is that they are surgeons at the top of their game, not necessarily female surgeons at the top of their game. That qualifier doesn’t even register for me. It’s not relevant. What is relevant is that I see them all as bad-ass surgeons and businesspeople I can learn from. Most of all, it’s obvious they care deeply about furthering the field of ophthalmology, and they’ve each made me feel like they care about me as I’ve begun my early career over these past 4 years.

6. As a woman, what do you think you bring to the table to mentor the future generation of ophthalmologists?

Dr. Arbisser:

Perhaps my example of longevity in teaching and my history of high-volume surgery while raising four children have served as a positive model. One unique way I mentor people now that I have retired from patient care is to go into their ORs, by invitation, as a coach and observe their surgeries. Depending on the surgeon’s performance, I may or may not have anything to say during the surgery, but afterward we review the cases together. I take notes during the cases, and we go over things with video and conversation that I might’ve done differently.

Dr. Brissette:

Having the perspective of being a woman in ophthalmology, I understand the importance of advancing women in academic medicine and on the podium, and I hope to provide sponsorship to many trainees in order to see them succeed. As we continue to push the conversation about the gender gap, we will only improve the experiences of women in this specialty.

Dr. Khandelwal:

It’s important that we be honest about the struggles that we have faced because that allows others to feel that they’re not alone. When a resident comes to me and says, “I’m struggling to balance call and my young child,” I’ll tell them stories of the things I’ve had to do. It’s a reality that most people go through, and that’s why they should continue to work at it.

Dr. Matossian:

Whenever I have an opportunity to invite or nominate people to become members of an organization, whether it is for CEDARS/ASPENS or the New York IOL Implant Society, I’m conscientious about nominating women as well as men. I love the opportunity to share and teach whenever possible.

Dr. McCabe:

I hope that I can be a source of information, an example of balance with career and family, and an inspiration to go further faster than I did.

Dr. McDonald:

I love being a mentor. I have learned a lot along the way that I am delighted to share with younger women—and with younger men. We are more alike than we are different!

Dr. Nijm:

As a mentor, I see my role as helping women ophthalmologists recognize their tremendous skill and talent and encouraging them to have confidence in themselves to achieve their career goals.