I founded Minnesota Eye Consultants 28 years ago. In the first year, with only six employees and me practicing in one office, we grossed just over $1 million in revenue. Since that time, we have expanded our practice to six offices, with a total of 14 ophthalmologists, 12 optometrists, and 300 employees practicing across them. We now gross about $45 million annually.

If someone had asked me about 2 years ago if retirement from active practice were in my near future, I would have probably answered affirmatively. I have had a long and successful career, and our practice has earned a strong clinical reputation in the past 28 years. Even though these accomplishments should make it easy for me to retire, because I enjoy the practice of ophthalmology, the decision continued to be a coin toss for me. On the other side of that coin was the fact that it is an exciting time to be in ophthalmology, and I wanted to be a part of that excitement. I especially wanted to participate in the meaningful consolidation of ophthalmology practices that has been happening in the Twin Cities and in other areas across the United States.

At about the same time I was contemplating retirement, private equity firms began to show interest in the ophthalmology space. Beginning around 2014, these investment management companies started fairly actively investing in operating practices in other health care sectors, namely dentistry,1 dermatology,2 emergency, medicine, radiology, anesthesiology, and behavioral health. Ophthalmology was a natural next step, because just like the other sectors I mentioned, it is not a completely hospital-dependent specialty.

So, rather than flip that coin, I thought about reinvesting it, moving toward consolidation in the fragmented ophthalmic market and toward partnering with other like-minded eye care providers in our direct market and potentially in other US markets as well.

WHY PRIVATE EQUITY?

The three ways to participate in the consolidation of ophthalmology are (1) being acquired by a large hospital system or accountable care organization, (2) creating a mega-practice from multiple independent practices, and (3) teaming up with private equity. We did not see the first two options as ideal: acquisition by a hospital results in an employee status with no equity integration, and creation of a mega-practice causes the other practices involved to compromise their culture and adopt yours. We were looking for a way to create a larger regional area delivery system with an equity integration opportunity, which would also allow each practice to maintain its own individual identity and culture. We felt that private equity made the most sense for two particular reasons.

Reason No. 1. Private equity provides access to capital. Minnesota Eye Consultants has grown significantly over the past 28 years, and we want to continue growing. When we decided to pursue private equity, we set a 10-year goal to grow twice as big as we were. That means employing 52 doctors and grossing $80 to $90 million annually. In an attempt to reach that goal, we decided to first build another large office on the east side of the Twin Cities, and we needed access to capital. Private equity provided us with that access without partner personally guaranteed bank loans.

Reason No. 2. Private equity allows a practice to monetize its value. We have always extended the option to younger associates to buy shares in the practice at a significantly discounted value, but the partners at Minnesota Eye Consultants, older and younger, began wondering whether there were another way to monetize some of the value that we had built over the years. What we discovered is that partnering with a private equity firm provided us with a higher multiple of earning before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization than what transferring ownership to younger associates did.

A LONG PROCESS, A POSITIVE OUTCOME

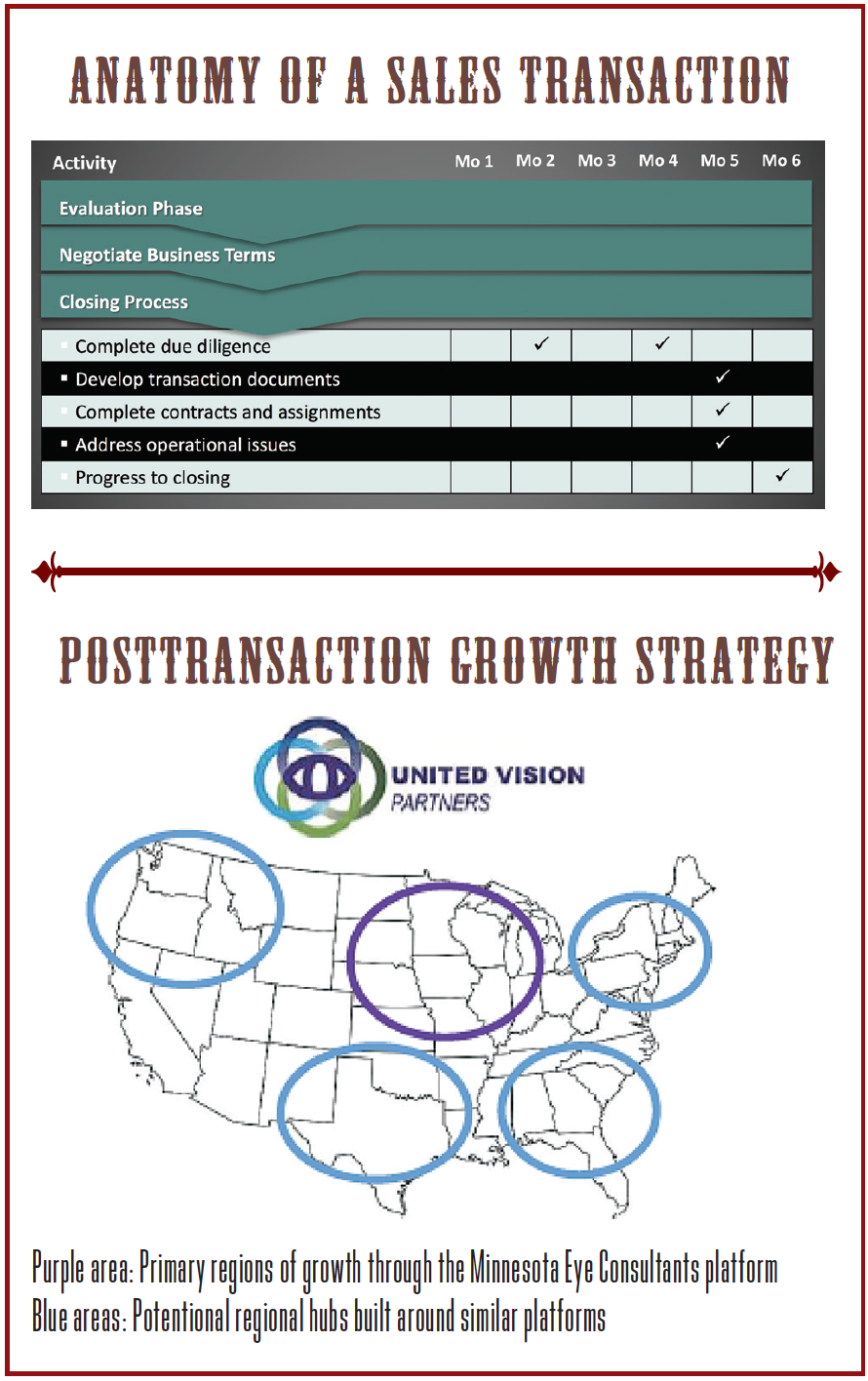

Making the decision to affiliate with a private equity firm required the partners at Minnesota Eye Consultants—at the time there were 10—to exercise due diligence in selecting the right firm (see Anatomy of a Sales Transaction). At the time, only one other ophthalmology practice, Katzen Eye Group in Baltimore, had done a transaction with the private equity firm Varsity Healthcare Partners. We spoke with Brett Katzen, MD, who said he had a positive experience; however, we were not sure that the Varsity model was exactly right for us.

We took our time—18 months—to identify the appropriate private equity firm for our own transaction, one that we felt had a culture and set of values similar to ours. In this time, we hired and worked with the broker Provident Healthcare Partners to whittle down our choices of private equity firms from 100 to 50 to 25 to 10 to three to one: Waud Capital.

Even though the decision was unanimous among the partners, it took us a while to get there. In large part, this was because we are between the ages of 34 and 69 and are all at different stages in our lives. The decision was probably a bit easier to make for those of us who were nearing retirement than it was for the younger doctors, but everyone consulted with their financial advisors and thought long and hard about what a private equity deal would mean for their futures. We had five go-no go votes, which we had agreed would be based on a super majority (7/10). We also decided that anyone who did not agree with the deal would receive a noncompete to freely practice elsewhere. As it turned out, all 10 of us came to the same conclusion, that we were in favor of partnering with Waud Capital. We also had a young doctor who was on a partnership track, and he became our 11th partner through the transaction (Figure).

Figure. The partners at Minnesota Eye Consultants.

CONTROLLING DESTINY

The private equity deal with Waud Capital went into effect on January 1, 2017. After about 7 months, a number of positive effects have already materialized. The first is that the Minnesota Eye Consultants partners are personally currently guaranteeing zero debt. The second is that all 11 partners, including me, received a meaningful cash payment as well as a go-forward equity position in Unifeyed Vision Partners (UVP), the strategic partnership now formed as a result of the private equity transaction (see Posttransaction Growth Strategy). The third is that all 11 partners are still happily practicing, which is, in part, because not much has changed with the way that we operate as a practice. The only small differences are that there is easier access to capital and that an additional core team of extremely bright business minds is helping to manage the practice. In the end, we are still the partner doctors in practice, and we are still helping shape our own destiny.

This contrasts to an experience I had with private equity back in the 1990s, when I was the chief medical officer and on the board of directors of Vision 21, a public physician practice management company. The number 1 thing that was different when Minnesota Eye Consultants partnered with Vision 21, from 1995 to 2000, was that the payout to the partners was entirely in stock, not primarily in cash like the transaction we recently made with UVP. A few doctors who joined public physician practice management companies and were wise enough to sell their stock at just the right moment did well, but most of us—me included—did not.

Another big difference between my experience with private equity is the models of management that each used. The Vision 21 model was a centralized management model, in which business professionals located in Florida managed the practice and planned the growth strategies, rather than the physicians and their local management team and advisors. Not only did this model create large centralized infrastructures, which were quite expensive, but it also replaced administrators who knew the local market with those who worked remotely and did not. As I mentioned before, the UVP model is to use a small decentralized core team that is additive; we have not replaced the local management team of the practice.

Even though the centralized model of Vision 21 did not turn out to be a good one for the reasons just mentioned, in other ways, we did quite well with it. While in partnership, we built about a $75 million regional area delivery system, which eventually collapsed because of excess overhead and poor centralized management. This collapse triggered the share price to collapse, and when it did, Vision 21 went into receivership and ended up being owned by the Bank of Montreal. Over time, the bank sold the practices back to the individual doctors, and we bought Minnesota Eye Consultants for about $2 million. One could argue that it was a positive thing, because over 5 years, Vision 21 had invested about $10 million in the practice. That was a great bargain, but it was also a pretty traumatic experience for us and our partners.

CONCLUSION

Anyone who looks around a large community can easily see market consolidation in health care by big groups like Kaiser Permanente and UnitedHealthcare and by large hospital systems that acquire practices. There are also mega-groups forming in most larger markets. Private equity is another form of consolidation—one that I think will be positive for ophthalmology, because it allows ophthalmologists who join to own equity and to be more independent than they would be if being acquired by a large multispecialty group or a hospital chain.

I am a strong believer in the power of equity integration in a partnership, and I personally want to own equity in any company where I am a significant creator of future value. Right now, statistically speaking, only about 30% of doctors own equity in their practices; that means at least two out of three doctors do not. In the private equity model, the doctor still owns equity and has an opportunity to share in the future created value by growing his or her practice. I like the idea of the doctors’ having a chance to own equity, which cannot be done if they practice at a university medical center or are owned by a large multispecialty group or hospital chain. I think private equity has the potential to account for 10% to 20% of ophthalmology practices over the next decade, and this percentage will consist primarily of entrepreneurial, motivated surgeons who want their practices to grow. The typical practice pursued by private equity will be one that owns or can partner in an ambulatory surgery center and offers cash-pay procedures such as refractive corneal surgery, refractive cataract surgery, ocular plastics, and optical.

It is worth considering that 18,000 ophthalmologists practice in the United States today. I would venture to guess that, 5 years from now, 1,800 to 3,600 may have partnered with private equity. The rest will still be employees of another consolidator or of an institution or continue in successful small and large private practices. There will be plenty of room for private practices that do not choose to join private equity to survive and thrive, but in my opinion, private equity is an option worth careful consideration.

1. Krause P. Private equity firms are suddenly buying dermatology practices — here’s why. http://www.businessinsider.com/why-private-equity-firms-buy-dermatology-practices-2016-8. Accessed June 23, 2017.

2. Shah-Khan M. Why are private equity and venture capital groups interested in dental practices? http://www.dentaleconomics.com/articles/print/volume-106/issue-12/macroeconomics/why-are-private-equity-and-venture-capital-groups-interested-in-dental-practices.html. Accessed June 23, 2017.