CASE PRESENTATION

A 34-year-old man sustains blunt trauma from a wrench to his left eye. The patient is initially treated in the emergency department, where he is diagnosed with a large hyphema and a perforating injury is ruled out. He is treated for several weeks with topical steroids and cycloplegic medications. Over the next few weeks, the hyphema resolves, but good vision does not return as the patient had hoped.

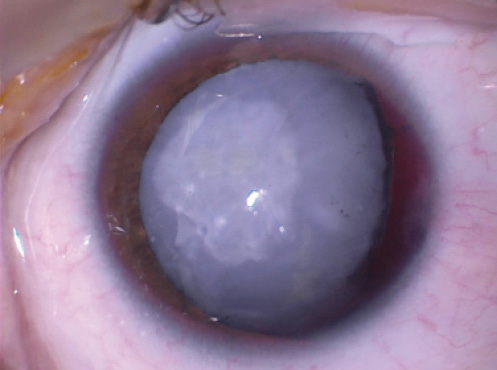

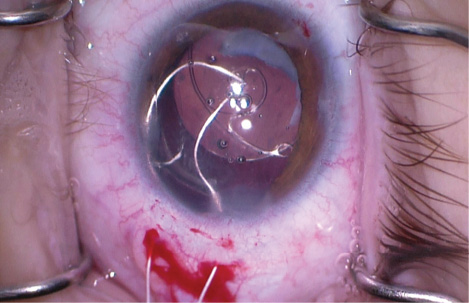

After 2 months of healing, the patient is referred for management of the resulting traumatic cataract in his left eye. Upon examination, the visual acuity measures 20/20 in the right eye and hand motion in the left. Pinhole does not improve the vision in the left eye. No afferent pupillary defect is noted in the left eye, and motility is full. IOP is within normal limits. A slit-lamp examination of the right eye is normal, and the left eye has a clear cornea. The anterior chamber is deep and quiet. The iris is partially atonic and dilated to 5 mm. The lens is white with scarring on the anterior capsule and mild nasal subluxation (Figure 1). Phacodonesis is not apparent on exam. No direct examination of the posterior pole is possible, but B-scan ultrasonography shows a flat retina with a likely old vitreous hemorrhage. The posterior capsule appears to be intact on the B-scan.

What would be the best approach to managing the anterior segment?

Figure 1. White cataract, nasal subluxation of the lens, and 4 to 5 clock hours of atonic temporal iris. The remaining 8 clock hours of the iris are functional. The pupil is pharmacologically dilated.

—Case prepared by Brandon D. Ayres, MD.

MARJAN FARID, MD

There are several considerations when managing a traumatic white cataract. Although there is no clear phacodonesis on examination, the severity of the blunt trauma should alert the ophthalmologist to a risk of zonular dehiscence and capsular instability during surgery. As such, he or she should be prepared with capsular tension rings (CTRs), Ahmed Capsular Tension Segments (CTSs; Morcher, US distributor FCI Ophthalmics), capsular hooks, and sutures for scleral fixation that may become necessary during the case to center and stabilize the capsule and IOL.

The scarring of the anterior capsule both diminishes the red reflex and increases the risk of capsular tear radialization. I would be prepared to use trypan blue dye to help with visualization during the capsulorhexis. It would also be worth considering the use of an ophthalmic viscosurgical device (OVD) that has a heavy molecular weight to flatten the capsule, because lens protein fluid tensions can cause rapid radialization of the capsular tear upon initiation, commonly known as the Argentinian flag sign.

In cases such as this one, I find it best to begin with a small capsulorhexis and to enlarge the tear after placing the IOL and centering it within the capsular bag. Anterior capsular scarring can make a smooth capsulorhexis difficult to achieve; small-incision intraocular scissors may be required to complete the capsulotomy across the scarred area.

During phacoemulsification, it is important to reduce manipulation and movement to preserve the zonules that are still intact. I find phaco quick chop useful for staying central and minimizing tension on the lens equator. Having anterior vitrectomy instrumentation on standby is important in case vitreous leaks around loose zonules.

For eyes like this one, I favor the versatility of a three-piece IOL. It can be placed in the sulcus or sutured to the sclera or iris if necessary. Furthermore, the spring-like haptics of a three-piece IOL act something like a CTS and improve centration of the lens. Ahmed CTSs may be required to center the entire capsule-IOL complex. My preference would be an aspheric monofocal lens, because mild decentration will not affect the patient’s quality of vision.

The traumatized iris requires repair. Gentle central stretching of the sphincter muscle would allow some of the peripheral anterior synechiae to be released and make more iris tissue available. I would use a nontoothed McPherson or small-incision, nonserrated forceps to gently stretch the tissue centrally and release scarred tissue from the angle. After instilling a miotic agent, I would determine whether an additional iris suture were required to create a functional pupil.

JEREMY Z. KIEVAL, MD

I would begin this case with a laser capsulotomy, which would not cut through the fibrotic capsule but would likely create at least a partial capsulotomy centered on the capsule. After administering a peribulbar block, I would stain the capsule with trypan blue dye and create a superonasal clear corneal incision. Assuming there was no vitreous in the anterior chamber, I would inject a dispersive OVD into the anterior chamber and insert two capsule retractors temporally to stabilize the bag. Completion of a continuous capsulorhexis would then be performed, likely requiring the fibrotic capsule that was not cut by the laser to be completed with microsurgical scissors. Gentle hydrodissection and cautious phacoemulsification using low flow settings should be sufficient to remove the lens of this young patient.

After removing the retractors, I would make two sclerotomies with a 25-gauge microvitreoretinal blade 3 mm posterior to the temporal limbus. I would insert an Ahmed CTS preloaded with a CV-8 Gore-Tex suture (W.L. Gore & Associates; off-label use) into the bag, position the fixation eyelet in the area of the weak zonules, and retrieve the suture ends with micrograsping forceps through each sclerotomy. I would pull the suture to provide just enough tension to secure the CTS without creating stress on the opposing zonules and then secure the device with a slipknot. I would then insert a CTR and place a three-piece monofocal IOL in the bag. After adjusting the final tension on the Gore-Tex suture to center the IOL, I would lock the suture with a final throw. I would rotate and bury the knot while holding the eyelet of the CTS with microsurgical forceps to prevent decentration of the IOL and bag.

Finally, I would perform a pupilloplasty by placing two interrupted 10–O Prolene sutures (Ethicon) using a McCannell technique. At the conclusion of the case, I would instill triamcinolone acetonide (Triesence; Alcon) to ensure there was no vitreous prolapse, constrict the pupil using acetylcholine (Miochol-E; Bausch + Lomb), and close the conjunctiva with 8–O Vicryl sutures (Ethicon).

D. BRIAN KIM, MD

This white cataract should be soft and fairly easy to remove. Because of the potential for zonulopathy, however, I would avoid sculpting or rotating the lens and employ a double chop and cross-chop mechanical fracturing technique.

The capsulorhexis can be challenging in cases like this one. Intumescent lenses present a high risk of a “run-out” and Argentinian flag sign, complicated by anterior capsular fibrosis. I would paint the capsule with trypan blue dye and then place a dispersive OVD. I would instill Healon5 (Johnson & Johnson Vision) to flatten the anterior capsule. Next, I would puncture the central capsule with a 27-gauge needle and aspirate cortical milk. I would then add more Healon5 to decompress and flatten the anterior capsule. Next, I would attempt to encircle the fibrosis with the continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis. If that were not possible, I would use intraocular scissors to cut through the fibrosis.

I would proceed with routine phacoemulsification, or if 3 to 4 clock hours of zonular dehiscence were present, I would consider a CTR. To minimize zonular stress, I would use an injector and capture the leading eyelet with a Sinskey hook to reduce contact between the CTR and capsular bag while advancing the ring to reduce rotational stress. If I discerned too much focal zonular instability, I would place capsular hooks in the area of weakness. Ultimately, an Ahmed CTS could be placed and sutured to the sclera for more permanent support.

With regard to the pupil, after IOL placement, I would inject acetylcholine and assess the area of atonic mydriasis. I would consider partial pupil cerclage with a Siepser sliding knot technique using 10–O polypropylene on a CIF-4 needle.

Watch It Now

In this episode of CRST Journal Club, Brandon Ayres, MD, discusses iris repair and replacement during cataract surgery.

JASON R. MAYER, MD

Although phacodonesis was not noted on the exam, given the slightly nasal displacement of the lens, I would assume zonular dehiscence temporally. I would stain the anterior capsule with trypan blue dye and take care to avoid overfilling while instilling a dispersive OVD so as not to cause more zonular problems. In eyes with white cataracts, I usually perform decompression with a 25-gauge needle on balanced salt solution through the capsule centrally to avoid the dreaded Argentinian flag. My goal would be to create a continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, but I would have microsurgical scissors (MicroSurgical Technology) on hand in case I could not avoid the anterior capsular fibrosis. Capsule retractors might prove necessary temporally to stabilize the bag for hydrodissection and phacoemulsification of the lenticular material.

After removing all of the lenticular material, I would insert a CTR and sew in an Ahmed CTS temporally for better centralization of the intended IOL. I would then implant the IOL in the capsular bag and remove the capsule retractors. Triamcinoline acetonide would facilitate the identification of any vitreous prolapse, because this patient will likely need a limited anterior vitrectomy.

I would bring down the pupil with acetylcholine. Depending on the amount of scarring, I would perform a pupilloplasty of the atonic iris with 10–O Prolene, either as a partial cerclage suture or an interrupted suture for a more natural appearance.

Watch It Now

See how Dr. Ayres managed this case.

WHAT I DID: BRANDON D. AYRES, MD

As with any complex case, I held a long discussion with the patient about the risks and benefits of cataract surgery. Afterward, he was scheduled for cataract removal with possible anterior vitrectomy, pars plana vitrectomy, and iris reconstruction, if possible.

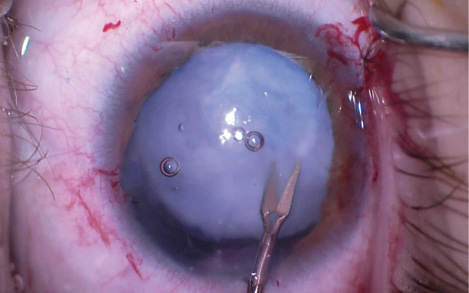

In eyes such as this one, the capsulorhexis is the most critical step toward a successful outcome. In this case, the cystotome was barely able to penetrate the fibrotic anterior capsule, and I had to use intraocular scissors to make the capsulotomy. The anterior capsule was thus left with a discontinuous capsulorhexis, which traditionally makes placing a CTR or CTS difficult (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Severe fibrosis of the anterior capsule requires the use of intraocular scissors to complete a discontinuous capsulorhexis.

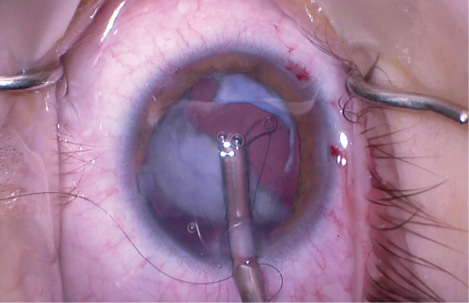

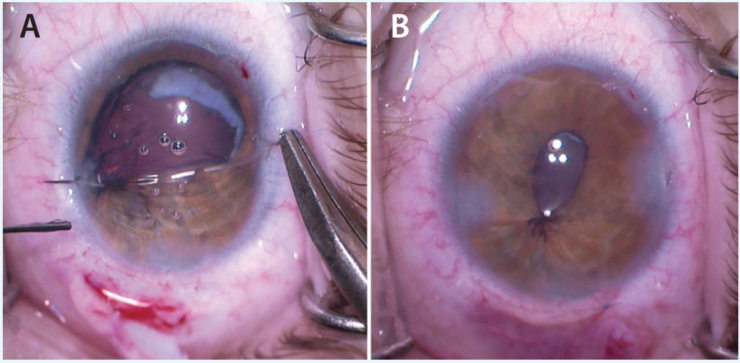

Because the patient was young, I was able to aspirate the white lens out without need for phacoemulsification. In place of the traditional irrigation/aspiration unit, I removed the lens with the anterior vitrector. Doing so allowed the safe removal of vitreous that had prolapsed around the edge of the dehiscence. Prior to complete removal of the lens, the need for a CTR became clear. Placing a CTR in a capsular bag with a discontinuous capsulorhexis can permit posterior extension of any anterior tear, but the fibrotic nature of the capsule enabled me to place the device successfully without this problem. To be safe, however, I laced a 10–O nylon suture through the eyelet to ensure that, if the CTR did open the capsule, the device could be easily retrieved and removed (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Placement of a CTR laced with a 10–O nylon suture prior to complete lens removal. In this eye, the anterior capsulorhexis has several small tears that could extend to the posterior capsule. The surgeon places a 10–O nylon suture to allow recovery and removal of the CTR if needed later in the case.

Figure 4. Bimanual anterior vitrectomy using triamcinolone acetonide to help visualize any vitreous in the anterior chamber.

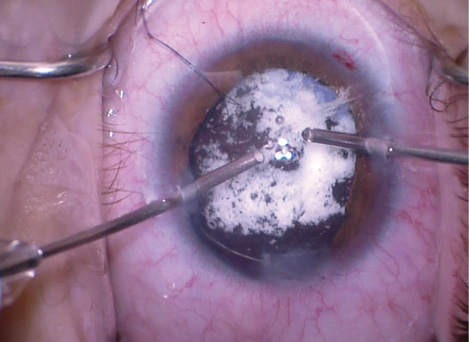

Placement of the CTR allowed me to remove the rest of the lenticular material and perform additional vitrectomy. I instilled triamcinolone acetonide to help me identify vitreous that had prolapsed into the anterior chamber (Figure 4).

I then implanted a single-piece acrylic IOL in the capsular bag without difficulty. To help secure and center the IOL, I created a temporal conjunctival peritomy and two scleral incisions 2 mm posterior to the limbus. I laced a Gore-Tex suture (off-label usage) through the eyelet of an Ahmed CTS. After the device was positioned in the capsular bag, the suture was on the scleral surface, allowing proper centration of the IOL (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Off-label use of a Gore-Tex suture to place an Ahmed CTS. Use of this device in an eye with an anterior capsular tear is not recommended, but in this case, severe capsular fibrosis makes it possible. The knot of the suture is buried in the sclerotomy and then covered by closure of the conjunctival peritomy. The eyelet of the segment will sit above the capsular bag in the sulcus space, while the CTS sits in the capsular bag. Sutures are not placed through the capsular bag.

Figure 6. The surgeon places a partial cerclage suture over the area of nonfunctional iris sphincter to help correct a large, irregular pupil (A). The eye at the completion of the surgical procedure (B).

Once the cataract portion of the surgery was complete, I turned my attention to the iris. Luckily, the tissue had not lost its elasticity, so I was able to place a partial cerclage suture using 10–O polypropylene. The knot was tied, leaving the pupil with a slightly teardrop shape that covered the edge of the optic. I cut the suture short in the anterior chamber, removed all viscoelastic, and sealed the incision (Figure 6).

The postoperative course was uneventful. By 1 month after surgery, the patient had recovered a UCVA of 20/50 with no complaints of glare. With correction, his visual acuity is now 20/30.