Eyelid surgery is one of the most gratifying areas in aesthetic surgery for both patients and physicians, because it addresses both functional and cosmetic concerns. Many of our patients present with functional problems as their chief complaint, as upper eyelid dermatochalasis and ptosis both cause loss of the superior visual field. In the elderly patient population, lower eyelid laxity, retraction, and ectropion are common and may contribute to functional concerns such as tearing and dry eye.

When patients have cosmetic concerns, they may opt for additional elective surgery. In our experience, patients are more likely to opt for elective surgery that addresses their cosmetic concerns if we can perform all procedures, both functional and cosmetic, through the same incision in one surgical setting with reduced morbidity and expense.

AT A GLANCE

- As cosmetic periorbital surgery has evolved, the line between functional and cosmetic surgery has blurred, with insurance covering less and patients expecting more.

- When the periorbital area is not treated as one aesthetic unit, unfavorable results often follow.

- Addressing the area as one unit minimizes expense, complications, and the number of incisions.

In our practice, we conceptualize two separate aesthetic units to treat the entire face and neck area. We consider the upper half, which we refer to as the periorbital unit, to be made up of the eyebrow, upper eyelid, lateral canthus, lower eyelid, upper cheek, and midface area. The lateral canthus is the keystone and critical anchoring point of this unit and is pivotal in creating a natural, happy, and youthful appearance in one aesthetic-unit periorbital surgery. We consider the lower unit to be composed of the lower cheek, lips, chin, jowls, and neck.

PERIORBITAL AESTHETIC UNIT

Surgery of the periorbital aesthetic unit is perhaps one of the most challenging areas in aesthetic surgery, as improving the cosmesis and height of the upper and lower eyelids may compromise coverage and protection of the cornea. When the periorbital area is not treated as one aesthetic unit, unfavorable results often follow. For example, upper eyelid blepharoplasty often improves cosmesis through the removal of redundant upper eyelid skin, but it can also worsen pre-existing dry eye by increasing the vertical palpebral fissure. Tightening the lower eyelid to improve laxity and retraction can help to avoid this problem.

Performing only upper blepharoplasty surgery in the presence of a ptotic eyebrow will actually worsen the patient’s eyebrow ptosis by pulling the eyebrow downward and decreasing the ability of the frontalis muscle to raise the eyebrow and eyelids. Similarly, raising the upper eyelid or eyebrow can make lower eyelid retraction and lateral canthal droop more apparent. Raising the lower eyelid, lateral canthus, or midface without raising the upper eyelid can make ptosis of the upper eyelid and eyebrow more apparent.

When the patient is concerned his or her upper eyelids have a sad, droopy, angry-looking appearance, it may be more associated with eyebrow furrowing caused by the corrugator and depressor supraciliaris muscles.

ONE UNIT APPROACH

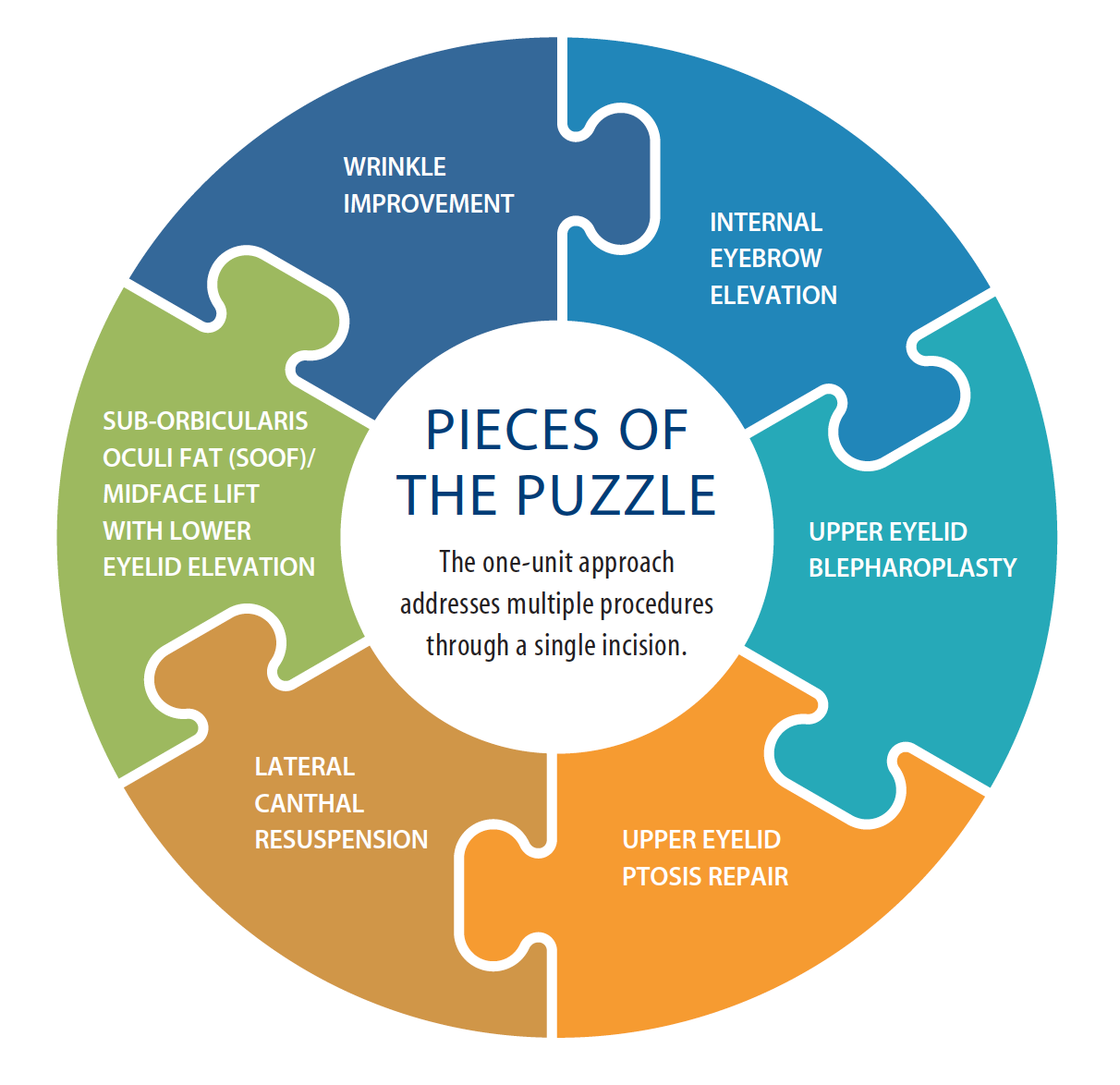

By addressing the periorbital area as one aesthetic unit (Figure 1), we are able to achieve excellent functional and cosmetic results. With this approach, we are able to minimize surgical expense, complications, and the number of incisions. Therefore, the patient acceptance rate is much higher than with other eyebrow or midface procedures that require multiple incisions. In the event that the patient has excess lower eyelid fat prolapse, tear trough deformity, and excess lower eyelid skin and wrinkles, transconjunctival fat removal and repositioning and trichloro-acetic acid peel can easily be performed in the same setting.

Figure 1. The one-unit approach can also remove the corrugator and depressor superciliaris muscles through the same incision to eliminate glabellar furrows and raise the medial brow, both of which often have the added benefit of headache relief.

The one aesthetic–unit approach to periorbital rejuvenation can also be performed in an outpatient minor procedure room, which can further decrease expenses and risks associated with anesthesia.

Patient Selection

Proper patient selection and analysis of each patient’s individual functional and cosmetic concerns is critical to forming a surgical approach within the periorbital aesthetic unit. Many of our patients present with functional concerns such as dermatochalasis, true ptosis, or lower eyelid retraction. This is a starting point for discussion about all of their other concerns, some of which may be cosmetic and not covered by insurance but certainly improve the outcome of the functional surgery as well as the cosmesis.

DRY EYE CONSIDERATIONS

The first, and perhaps most important, question is whether the patient has dry eye or uses artificial tears. If a patient says that he or she has dry eye, it is important to assess the tear film and cornea at a slit-amp examination with fluorescein staining to evaluate the severity of their dry eye. While this does not preclude the performance of surgery that may widen the palpebral fissure, we are more careful about recommending ptosis or blepharoplasty surgery unless we also plan to perform surgery that will raise and tighten the lateral canthus and lower eyelids. In these cases, we may also consider performing bilateral punctal occlusion with electrocautery or dissolvable collagen plugs at the time of surgery so that the patient will retain more tears.

If a patient presents with tearing, then the surgeon must evaluate the lacrimal system. Often, patients have tearing because of reflex lacrimation from the lacrimal gland in response to a dry eye. Some patients may also have a true obstruction of the tear drainage system. This distinction can be made by a dye test and nasolacrimal system irrigation in the office. Many older patients with lax lower eyelids also suffer from pump failure and lateral pooling of tears. Tightening the lower eyelids and elevating the lateral canthus at surgery can improve such tearing.

PTOSIS

The surgeon should evaluate all patients for eyebrow ptosis. Normal eyebrow height is at least 1 to 2 mm above the superior orbital rim in women and at or just above the orbital rim in men. The presence of eyebrow ptosis should alert the surgeon that performing upper blepharoplasty alone will further drop eyebrow height and, in doing so, worsen the angry appearance that was the patient’s initial presenting complaint. At the same time, the surgeon should evaluate the corrugator and depressor superciliaris muscles, which also contribute to eyebrow ptosis and a scowl-like appearance.

When considering whether a patient has ptosis of the eyebrow warranting surgical correction, it is imperative to remember that any tissue removed as part of a standard blepharoplasty correction will further drag down the brow. Performing blepharoplasty alone has been shown to decrease preoperative brow height by 2 mm.1,2

As the brow descends inferiorly with time, the frontalis muscle must work harder to elevate this displaced tissue. Elevating a droopy eyelid leads to less stimulation of the frontalis muscle and potentially some inferior traction from the incision below the brow, both of which may lead to more brow ptosis.1,2,3 As the distance between the eyebrow and the eyelashes decreases, the face assumes a more sad and angry appearance. This is likely the main reason patients are dissatisfied and may aesthetically look worse despite successful prior functional treatment of dermatochalasis and/or ptosis. Unfortunately, eyebrow ptosis must be severe, with the eyebrow blocking the visual axis, to get insurance approval.

We have previously reported our findings of obtaining a 1.74 ± 0.05 mm temporal brow lift using our internal brow-pexy technique through an upper eyelid crease incision.4 This works in concert with raising the medial brow by performing removal of the corrugator and depressor superciliaris muscles. While endoscopic, pretrichial, and direct brow lifts also create temporal lift, those techniques usually require deeper sedation or general anesthesia. The approaches create additional scars, are not suitable for certain hairlines, increase surgical costs for the patient, and have increased morbidity and complications secondary to the need for additional incisions.

We counsel all patients who present for evaluation of dermatochalasis or upper eyelid ptosis about the potential for worsening of any preexisting eyebrow ptosis if we do not address the eyebrows as well. Internal eyebrow elevation and sculpting with corrugator and depressor superciliaris muscle removal raises the medial brow as much as other more aggressive forehead techniques.5 This approach also relieves furrowing between the eyebrows, effectively creating a “permanent neurotoxin” effect. If the medial aspect of the eyebrow is elevated higher than the central and lateral aspects, a patient may be left with a quizzical expression. Additionally, male patients may be left with a more feminine appearance if the temporal aspect is overelevated,4 as typical male eyebrows are usually flatter horizontally, and female eyebrows tend to arch more laterally.

THE SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Our technique begins with an upper eyelid blepharoplasty with skin and muscle removal to correct any dermatochalasis. We use a No. 15 blade to make the skin incision and then remove a flap of skin and underlying orbicularis oculi muscle using Stevens scissors and Paufique forceps. This creates an “open sky” view of all the structures of the upper eyelid. If we visualize a levator aponeurosis dehiscence at this time, we repair it with one or two interrupted 5–0 polyglactin sutures. We debulk the upper eyelid fat pads with Stevens scissors and bipolar cautery if necessary. The skin and muscle removal not only provides lateral eyelid crease formation, but it is also important to elevate the eyebrow, lateral canthal area, and midface. The removal of the temporal orbicularis is similar to permanent neurotoxin under the temporal brow, and it provides direct access for brow sculpting and release. It also provides a natural space in which to raise the lateral canthus and midface.

To perform an internal eyebrow lift, we grasp the orbital retaining ligament with Paufique forceps at the lateral edge of the upper blepharoplasty incision and excise the orbital retaining ligament en bloc. The anterior leaf of the posterior galea, from the lateral edge of the blepharoplasty incision extending three-quarters of the distance across the eyebrow, is released. This allows us to lift the eyebrow internally by removing tissues tethering it in a lower position. We sculpt the inferior portion of the eyebrow fat pad, taking care not to overskeletonize the eyebrow.

Next, we resuspend the eyebrow fat pads to the posterior leaf of the posterior galea with 4–0 polyglactin suture and attempt to correct any asymmetry that was present preoperatively. Suturing to the posterior galea, rather than the periosteum, is important, as it allows the eyebrow to elevate with contracture of the frontalis muscle.

To achieve even greater medial brow lift, we can resection the corrugator and depressor superciliaris muscles. We perform blunt dissection toward the superomedial edge of the blepharoplasty incision with Stevens scissors to separate the corrugator and depressor superciliaris muscles from the overlying orbicularis oculi muscle. We bluntly dissect the orbicularis and retract it superiorly to expose the furrow muscles. We can then see nerves running vertically in the fascia overlying the corrugator muscles. We grasp the lateral edge of the corrugator muscle with Adson-Brown forceps and remove it en bloc with Stevens scissors along with the depressor superciliaris muscle. We use bipolar cautery for hemostasis. Removing the muscles en bloc instead of piecemeal ensures complete removal of the muscle and reduces intraoperative bleeding and postoperative bruising in this well-vascularized area of the face.

We bluntly undermine the muscles at the root of the nose, further raising the medial brow. Supraorbital anesthesia and hypoesthesia are expected for months after removal. However, furrowing and headaches—if present—are often greatly improved.

Next, we use the lateral extent of the upper blepharoplasty incision to perform both lateral canthal resuspension and midface/suborbicularis oculi fat elevation. We use blunt dissection with Stevens scissors to separate the orbicularis oculi muscle from the underlying periosteum in the lateral canthal region, midface, and cheek area. Blunt dissection allows direct access to the lateral canthal tendon. We then use a 4–0 polyglactin suture on the inferior crus of the lateral canthal tendon superiorly to the internal lateral orbital rim periosteum adjacent to Whitnall tubercle. This elevates the lateral canthus. We then advance the previously created myocutaneous flap and suture it to the lateral orbital rim periosteum adjacent to the lower edge of the blepharoplasty incision, also using 4–0 polyglactin suture on a P-2 needle. This elevates the mid-face and cheek while also improving lateral and lower eyelid rhytids.

We inspect all edges of the upper blepharoplasty incision and use bipolar cautery as needed for hemostasis. We close the skin using a combination of single, interrupted, and running 6–0 plain gut sutures to allow for egress of any postoperative residual bleeding through the skin as opposed to back into the orbit. Postoperatively, we suggest ice compresses for 72 hours and then warm compresses to reduce bruising. We encourage gentle pressure over the eyelids and brow every 2 hours for the first 2 days to encourage egress of any blood. The patient applies steroid/antibiotic ointment to incisions daily for 2 weeks. We place all patients undergoing eyelid surgery on topical, preservative-free artificial tears and artificial tear ointment at bedtime.

HEADACHE REDUCTION

If patients demonstrate aggressive medial brow furrowing or depression on exam, or if they complain of migraine or tension-type central headaches, we encourage removal of the corrugator and depressor superciliaris muscles. We have previously demonstrated that more than 90% of patients had a decrease in the severity of their headaches, and almost 60% achieved complete resolution of their pain following surgical removal of the corrugator and depressor superciliaris muscles.6 When discussing this surgery, patients must always be informed of the high likelihood for postoperative numbness and hypoesthesia in the forehead and between the brows, which may last for months. Neurotoxin use in this area is an alternative that we discuss with patients.

UPPER EYELIDS

After evaluating the eyebrows, we assess the upper eyelids, including the length of the anterior lamella. We prefer to leave more than 22 mm of anterior lamellar skin behind after upper eyelid blepharoplasty surgery to reduce the risk of lagophthalmos and dry eye.

In evaluating the lower eyelids, one should look for signs of lower eyelid retraction, entropion, and ectropion, including inferior scleral show, inferior conjunctival injection, corneal staining with fluorescein, or pooling of fluorescein in the tear film.

If conservative medical therapy for dry eye or tearing has been unsuccessful, it is important to discuss surgical options, because upper eyelid surgery can significantly worsen corneal exposure and dry eye. In patients with dry eye, tissue excision must be more conservative, and punctal occlusion in the upper eyelids can be helpful in preventing further worsening of dry eye. Tightening and raising the lower eyelids should also be considered.

LOWER EYELIDS

For many years, the lateral tarsal strip was the mainstay of our treatment for lower eyelid laxity and involutional ectropion. This is still an excellent technique in severe functional cases and in cosmetic cases with marked laxity. However, in our aesthetic patients and those who would benefit from midface elevation, we prefer lateral canthal resuspension and midface lift. Midface lift can be conveniently performed in a sequential manner through the lateral aspect of a blepharoplasty incision. Lateral canthal resuspension is also effective for mild to moderate ectropion without midface elevation.7 With aging, as the lateral canthal ligament stretches, the horizontal length of the lower eyelid diminishes, and patients may develop a small or round eye appearance.8,9 Further shortening of the eyelid with full-thickness excisions often also leaves aesthetic patients unhappy.

Lateral canthal tightening and suspension are the keystone in periorbital cosmetic surgery and paramount in treating the brow, upper eyelid, lateral canthus, and midface as one aesthetic unit. Midface and suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) lift is obtained by fixating a lateral orbicularis pedicle flap to periosteum in the interior, superolateral aspect of the orbital rim. This improves rhytids in the lower lids, moves the descended SOOF and cheek fat pads superiorly, and can also improve tear trough deformity when present. Limited supraperiosteal dissection is required to elevate the midface. Also key to the procedure is upper eyelid skin and orbicularis muscle removal, as well as internal eyebrow sculpting with release of the anterior leaf of the posterior galea and orbital ligament to move the entire lateral periorbital tissues both superiorly and laterally as one aesthetic unit.

Based on our long-term results, we routinely encourage patients with mild to moderate lower eyelid laxity to consider a midface/SOOF lift in addition to lateral canthal resuspension. This elevation improves both function and cosmesis and can be performed through the lateral portion of the upper eyelid crease incision. For patients with severe laxity, ectropion or entropion, or those with lamellar deficiencies, we still perform the typical or enhanced lateral tarsal strip procedure.8,10,11

Discussion

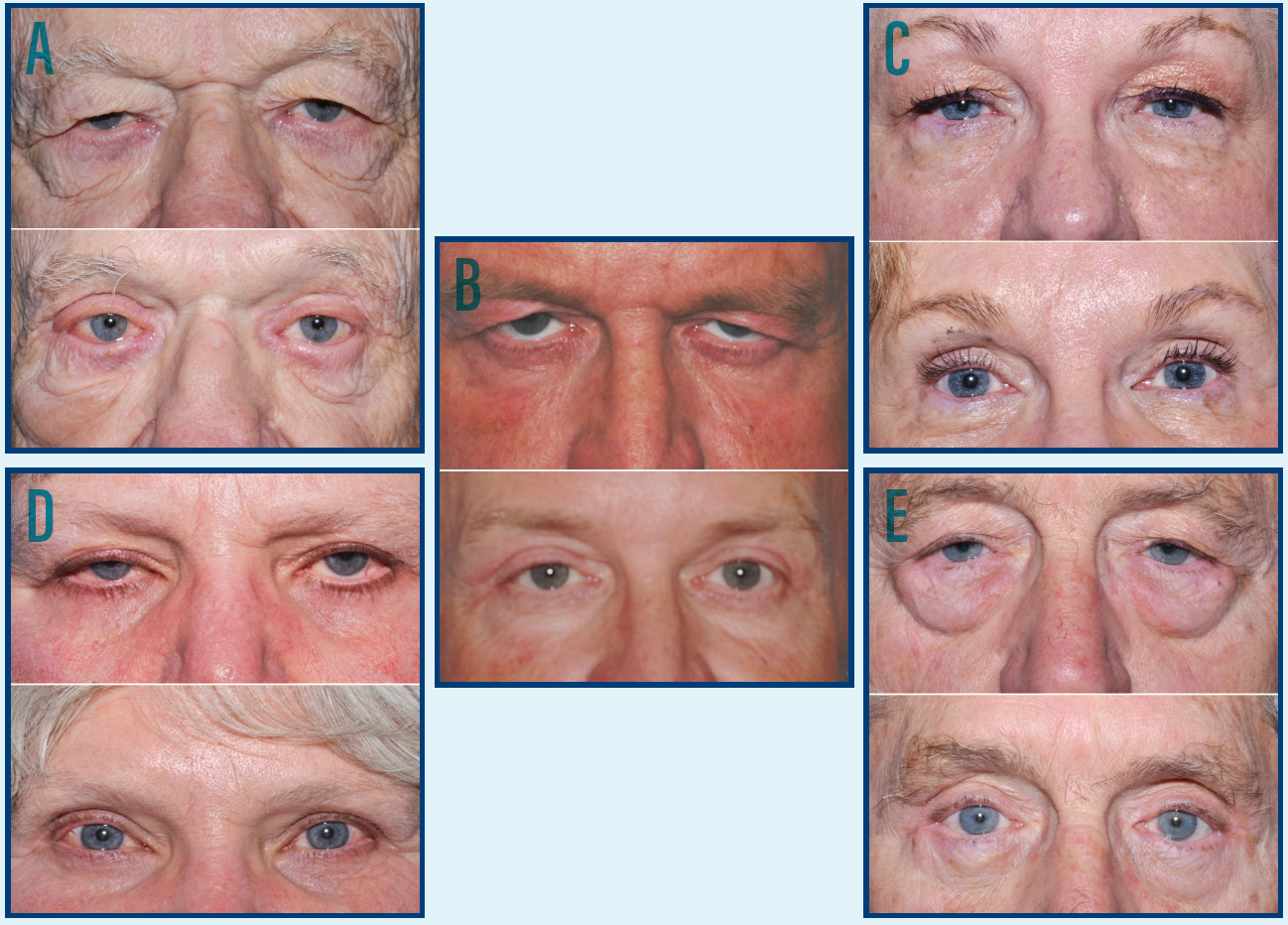

The upper eyelid crease incision has become the gateway to performing the majority of surgeries in our practice. Treatment of eyebrow ptosis, glabellar furrows, eyelid ptosis, upper eyelid dermatochalasis, lower eyelid laxity, and midface laxity are now all performed through this one aesthetic–unit incision. Being able to treat the entire periorbital aesthetic unit in one setting has greatly enhanced both functional and cosmetic results for our patients. The senior author (R.L.A.) has experienced gratifying results in more than 2,000 procedures using this one aesthetic–unit technique. Figure 2 represents results we have obtained with one aesthetic unit surgery, and except where indicated, transconjunctival lower lid blepharoplasty was not performed.

Figure 2. A) An 82-year-old male patient shown at postoperative month 1, following one aesthetic–unit surgery in the periorbital area and corrugators removal. This patient still has some residual, mild edema of the bilateral upper eyelids. B) A 58-year-old male patient shown at postoperative month 2 following one aesthetic–unit surgery in the periorbital area and corrugators removal. He still has more upper eyelid swelling on the right than the left. C) A 65-year-old female patient shown at postoperative month 4, following one aesthetic–unit surgery in the periorbital area and transconjunctival lower eyelid blepharoplasty with fat removal and repositioning. D) A 66-year-old female patient shown at postoperative month 3, following one aesthetic–unit surgery in the periorbital area. E) A 79-year-old male patient shown at postoperative month 4.5, following one aesthetic–unit surgery in the periorbital area and transconjunctival lower eyelid blepharoplasty with fat removal and repositioning.

We believe the lateral canthal angle is the keystone and anchor point in the periorbital aesthetic unit and thus proper surgical placement of the lateral canthus is paramount to successful surgery. The combined surgical approach described herein provides an effective method of restoring a natural, rejuvenated appearance to the lateral canthal angle. Lateral canthal resuspension allows us to effectively lengthen and raise the lateral canthal angle while simultaneously increasing its sharpness without disrupting the natural supporting tissues. The lower eyelid and midface are a continuum with the lateral canthus, and thus elevating and tightening the canthus simultaneously also improve lower eyelid rhytids and the appearance of the midface.

The one aesthetic–unit approach has numerous advantages. Use of a single incision increases our efficiency in the OR and leads to decreased surgery, along with its associated risks and costs. Rehabilitating the entire periorbital aesthetic unit in one session also requires only one recovery period and a single cosmetic incision site with less swelling, pain, morbidity, complications, and cost than other procedures in our experience.

As cosmetic periorbital surgery has evolved, the line between functional and cosmetic surgery has become more blurred, with insurance covering less and patients expecting more. Most patients are no longer satisfied by the simple correction of a functional deficit. We believe they are justified in this belief, as correction of functional problems may further aggravate cosmetic problems. The modern patient is also more aware that overly aggressive cosmetic surgery leads to an unnatural appearance. Based on our examination and discussion with the patient, we recommend surgery that recreates the most natural and youthful appearance possible for the patient. Treating the entire periorbital aesthetic unit provides a powerful yet natural outcome.

1. Lemke BN, Stasior OG. The anatomy of eyebrow ptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(6):981-986.

2. Knize DM. An anatomically based study of the mechanism of eyebrow ptosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97(7):1321-1333.

3. Burroghs JR, Bearden WH, Anderson RL, et al. Internal brow elevation at blepharoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8:36-41.

4. Georgescu D, Anderson RL, McCann JD. Brow ptosis correction: a comparison of five techniques. Facial Plast Surg. 2010(26);186-192.

5. Harstein M, Massry G, Holds J. Pearls and Pitfalls in Cosmetic Oculoplastic Surgery. New York: Springer. 2015.

6. Bearden WH, Anderson RL. Corrugator superciliaris muscle excision for tension and migraine headaches. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:418-422.

7.Georgescu D, Anderson RL, McCann JD. Lateral canthal resuspension sine canthotomy. Ophthal Plast Recontr Surg. 2011;27:371-375.

8. Jordan DR, Anderson RL. The lateral tarsal strip revisited. The enhanced tarsal strip. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:604-606.

9. Taban M, Nakra T, Hwang C, et al. Aesthetic lateral canthoplasty. Ophthal Plast Recontr Surg. 2010;26(3):190-194.

10. Olver JM. Surgical tips on the lateral tarsal strip. Eye (Lond).1998;12:1007-1012.

11. Vagefi MR, Anderson RL. The lateral tarsal strip mini-tarsorrhaphy procedure. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2009;11(2):136-139.