INTRODUCTION

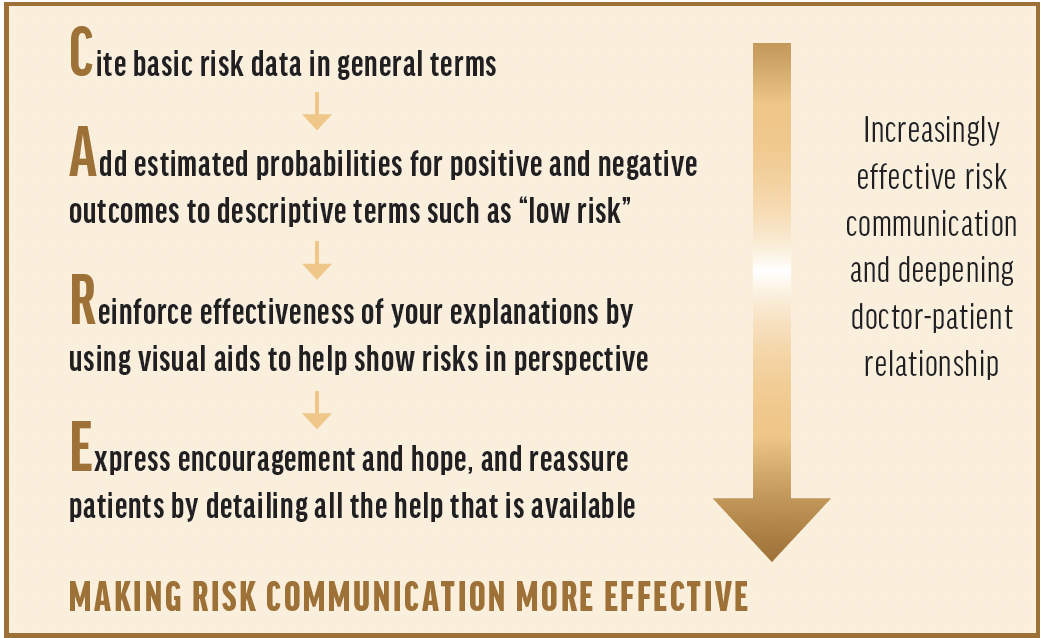

Learning to communicate both the true benefits and risks of treatment options and surgical approaches with patients is not simple, but it is crucial to meet their expectations. Most patients assess risks based on emotions rather than facts,1 and therefore eye care professionals (ECPs) must learn to adopt a caring and competent approach to communicating medical risks to patients. This includes reminding patients that all treatments are associated with the inherent risk of possible harm and reassuring them that their team of ECPs will do their best regardless of what treatment or surgery is chosen. More effective tips, found in the Figure, can help to enhance the trust between doctors and their patients.

Figure. Tips for effective risk communication. [Adapted from: Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003:327:745-748.]

The following discussion is designed to explore the challenges ECPs face when making clinical decisions for their patients and how they can customize their approach to care by weighing the risks and rewards as presented in the scientific literature. As tempting as it can be to obtain information from social media, the most appropriate way to become educated on medical innovations, procedures, and treatments is to perform literature reviews, talk to trusted colleagues, and make science-based decisions using personal clinical judgement.

Guiding clinical decisions based on data can safeguard against patients relying on misinformation they found online or on social media.

CRST: In your day-to-day, what do you do that carries some level of risk?

Y. Ralph Chu, MD: Obviously, the main area of risk is that I perform surgery. The higher level of risk I see with refractive-based treatments is that I am trying to improve my patients’ visual function and spectacle independence, which comes with a larger risk of not delivering on patients’ high expectations than treating a medical condition would.

Jessica Heckman, OD: I spend a lot of time providing surgical recommendations for patients, including their candidacy for refractive surgical procedures and cataract surgical technologies. I also care for patients with various medical ocular conditions including glaucoma and corneal pathologies. As Dr. Chu said, all of these things carry risks.

Jennifer Loh, MD: Every patient I see has some risk factors that could affect their surgical or treatment outcomes. Any medical decision we make or don’t make can ultimately affect the patient. There is always a risk of intraoperative complications. But there are also the risks of making a judgment error or planning for surgery ineffectively, such as the kind of IOL we select or the IOL power we use.

Justin Schweitzer, OD: My role is to prepare patients for a variety of ophthalmic surgeries, discuss options with them, and manage their care postoperatively. In all my roles, I encounter a variety of risk on a daily basis, such as setting proper expectations for the surgical procedure, making sure nothing about their ocular health is missed during the preoperative examination that could create surgical complications, and identifying postsurgical complications in a timely fashion so treatment can be initiated.

CRST: Outside of social media, how do you inform yourself on new technologies and therapeutics, prescribing and utilizing products, and performing procedures?

Dr. Chu: More information is available today than ever before. When I started my career, peer-reviewed journals were the gold standard for learning about new techniques, therapeutics, and technologies. I continue to rely on the literature, and I also read trade publications because they provide more immediate and up-to-date information in terms of therapeutics and surgical techniques and technologies. The most powerful way I learn about new technologies and therapeutics and the risks associated with them, however, is talking to trusted colleagues who have like-minded approaches to patient care. This also provides clear insights into how my colleagues navigate patient expectations.

Once I’ve made the decision to incorporate a technology into my practice, oftentimes, I visit a colleague who is either participating in the clinical trial for, or was an earlier adopter of, the technology. Seeing how they’ve implemented it and approach patient education and selection and getting a feel for how their patients accept it is a great way to minimize risks with the procedure, especially early in the learning curve.

Dr. Heckman: I inform myself on new technologies using multiple platforms, including peer-reviewed literature, presentations at conferences, clinical case reviews, and clinical experience from case discussions with colleagues.

Dr. Loh: In addition to what has been said, I find huge benefit from going to conferences because it provides an avenue to learn high-yield information in a formal structure. On my first day of clinical practice outside of training, I remember realizing that there were no more formal lectures and no attending guiding me. Losing the outlets we have during formal education residency program puts the burden, understandably, on the physician to reach out and learn on their own. Beyond ophthalmology conferences, I find reading the academic and trade journals to be helpful. The clinical experiences of my colleagues are also important. Evidence-based medicine is great, but I value hearing what my colleagues think through personal clinical anecdotes and surgical videos.

Dr. Schweitzer: I couldn’t agree more with what everyone else has said. I use a variety of avenues to stay current. Peer-reviewed literature, attending conferences, meeting with industry to stay current on what is new and what is coming, listening to a variety of different podcasts, reading a variety of journals, and learning alongside our team of doctors, residents, and fellows at Vance Thompson Vision are all part of the way I keep myself informed.

CRST: In today’s technology age, information about medical procedures and treatments is readily available to patients. How do you overcome medical misinformation through patient education?

Dr. Chu: This is a big source of chair time. Without a medical background, it’s difficult for patients to understand the nuances of a procedure or the difference between what is said in the published literature and on social media, for instance. The only way to combat this is taking the time to reeducate patients. This should start before they enter our doors.

Dr. Heckman: To build on what Dr. Chu said, if a patient calls for an appointment about a surgery or even a presbyopia drop technology, we start the educational process with a telehealth visit. That helps reset the conversation. Once they are in the practice, one of the main strategies I use to overcome medical misinformation is to educate patients on their specific situation. Providing patient-specific information often allows a smoother discussion regarding why a certain technology or treatment may or may not be appropriate for the patient and their specific needs.

Dr. Loh: I let patients know I think it’s great they took initiative to look for information on their own because it shows they’re proactive and care about their health. I embrace that, and if the information they gathered is inaccurate, I correct the misinformation and clarify the finer points of the condition and the procedures they are interested in.

Dr. Schweitzer: Arguably the most important part of a patient visit to our clinic is the time spent educating them on the nuances of their condition and the treatment options available to them. Like my colleagues have mentioned, I overcome medical misinformation by taking the time to educate the patient thoroughly, and I back it up with peer-reviewed literature. I think it is important to educate patients at a level they can understand but equally as important to mix in the literature studies that support the information I share.

CRST: What is your strategy for patient selection and ruling out high-risk patients for procedures like advanced technology IOLs, presbyopia drops, and LASIK?

Dr. Chu: We start evaluating a patient’s candidacy before they even come to the office. Our telehealth team not only gathers information about the patient but starts educating them about their options and the associated costs. Depending on how the patient reacts to the information often helps inform our decision of what technologies to offer. We rely on diagnostic testing to help us rule out patients based on their medical conditions and evaluate their personalities, tolerance for stress and uncertainty, and their understanding of the limitations of the technology.

Patient selection is a learned skill. For IOL selection, we evaluate how similar patients responded to certain technologies and adjust our recommendations accordingly. I’ve been doing refractive cataract surgery for 25 years, but patient demands and lifestyle choices are different now than they were then. Trying to match the available IOL technology to the patient is probably one of the most challenging parts of what I do. The same is true for refractive surgery. I spend a lot of time deciding what procedure is best for the patient and educating them on why they are a good candidate for that procedure. It’s about looking at the entire picture—the patient’s expectations, needs, and ocular health with advanced diagnostics. Now that we are better at patient selection, we are also better at discussing the risks associated with their procedure. We also have more options than ever before to say yes to patients.

It’s an exciting time for our presbyopia patients. In addition to advanced-technology IOLs, we can also prescribe presbyopia drops (Vuity; pilocarpine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution 1.25%, AbbVie/Allergan). The classification system published by McDonald and colleagues2 has been helpful to educate our staff and set guidelines for the conversations we have with different classifications of patients. We learned that age isn’t the biggest determinant for patients’ experiences with the drops, and now we guide the conversation based on their uncorrected near visual acuity and accommodative power. Checking their vision before any drops are put in, without glasses, helps dictate their potential for improved vision.

Dr. Heckman: A full and detailed assessment of patients’ ocular health using ocular surface assessment, topography and tomography, wavefront analysis, and OCT will start to rule in/out a patient for a particular technology. Thereafter, a frank, detailed discussion regarding visual expectations and the risks and benefits of a particular technology helps narrow the pool of procedures we offer to patients. Lastly, providing written information for patients to review improves their understanding of the procedure.

Often, refractive surgery patients require more than one visit before surgery. A follow-up in-person or a virtual discussion can be beneficial when additional time is needed for questions and to ensure appropriate understanding of the surgical procedure and expectations going forward.

Dr. Loh: For me, patient selection begins with taking a detailed history, including an ocular exam and finding out the patient’s occupation, hobbies, and preferences. These two strategies rule some patients out for an advanced-technology lens or refractive surgery procedure. For patients with irregular astigmatism, for instance, I am more cautious about using a toric IOL, and for patients with a macular pathology, I am more cautious about using a presbyopia-correcting IOL.

For patients who are interested in presbyopia drops, I have an open and honest conversation with them. I recommend they have an exam with me if they haven’t had one recently. If they are a candidate based on their level of presbyopia and their refractive status, I talk about possible side effects and any warning signs they should look for once they initiate drop therapy. I proactively address the issue of retinal detachment because it’s been in the media. I tell patients why I think they are a good candidate for the drop and inform them that they should let their eye doctor know if they notice any signs of retinal detachment.

Dr. Schweitzer: We lean on diagnostic technologies, peer-reviewed literature, patient education, and a mindset of “what would I do if this was my mom/dad/brother/sister” at our practice to guide patient selection.

CRST: How do you prepare patients for the risks of surgery, such as the risk of retinal detachment with cataract surgery and presbyopia drops, dysphotopsias with certain IOL technologies, and post-LASIK ectasia or other complications after laser vision correction?

Dr. Chu: The first and obvious thing is education. For some technologies, there is software available that allows patients to simulate what their vision could be like after IOL surgery. Any tool that empowers patients to trial something is powerful. For other things, like the risk of retinal detachment with cataract surgery or presbyopia drops, a conversation with patients is needed.

No matter what procedure or treatment patients are undergoing, the key is to be honest and straightforward with them without creating unnecessary fear. If you take presbyopia drops, for example, there were no retinal detachments in the FDA trial.3 We still recommend a dilated retinal exam for our patients, and we also discuss risk of retinal detachment with this class of miotic drops.

We prepare patients for presbyopia drops almost in the same way we prepare refractive surgery patients for their procedures. Both require setting proper expectations and educating patients on what could happen, including any side effects. For presbyopia drops, patients must understand that it takes about a week to break into the drops and that there is some chance of headache, blurred vision, and eye redness. We also tell them that there are techniques to overcome the side effects so that they understand it’s not that the drop isn’t working, it’s just the normal side effects. For refractive surgery, we go over the risks but also explain that both laser technology and our diagnostic capabilities have improved over the past 25 years. We explain that we are better at detecting things that we can’t see with the naked eye and screening patients.

Dr. Heckman: We use verbal and written education to prepare patients for the risks of surgery. As Dr. Chu mentioned, utilizing technology-visual simulators is powerful. Even a quick follow-up exam or pre-exam virtual education can assist in solidifying patient understanding.

Dr. Loh: For cataract surgery patients, I mention that there could be some sort of dysphotopsias associated with IOL implantation. I tell patients that nothing is quite the same as their natural crystalline lens and that, with certain diffractive IOL technologies, there’s a higher risk of having what patients describe as halos or glare, but most of those patients don’t find it bothersome and notice that it goes away over time. If they were to be bothered by the dysphotopsias, they may elect to have the lens exchanged.

For laser vision correction patients, I tell them about the risk of ectasia. My biggest concern typically with laser vision correction, however, is an infection. I explain the risk to patients and share that there are other things that we do, such as contact lenses, that can also cause infection, and that we put measures in place such as using antibiotics and sterile technique to reduce the risks.

Dr. Schweitzer: It all goes back to a thorough examination and patient education. A patient who is undergoing cataract surgery needs to know that, although a very safe surgery, it is still an intraocular procedure and the risk of a retinal detachment or endophthalmitis does exist. Patients sign a consent form before surgery, but they also hear it from me in the preoperative examination. Diagnostic technology, patient motivation, and setting proper expectations help with the discussion around dysphotopsias. If the patient has a healthy eye, I have treated the ocular surface aggressively, and I have set proper expectations around the IOL technology, it is uncommon to have a disappointed patient. I verbalize those exact words to patients and make a notation in the chart that I have had that discussion.

Regarding presbyopia drops and the risk of retinal detachments, I make sure to choose the proper patient and educate them on the risks. Patients undergo a complete eye examination and visualization of the peripheral retina. If the eye is healthy, they are not a high myope, and the peripheral retina is healthy, I am comfortable prescribing presbyopia drops. All medications that we prescribe daily have risks; we just need to make good clinical decisions around each one. A presbyopia drop is no different.

When it comes to refractive surgery and decreasing the risk of postrefractive surgery ectasia, I lean on a variety of tests. Tomography helps me to understand the anterior and posterior corneal curvature, corneal thickness, and a combination of other factors that can help raise a red flag of an increased risk for postrefractive surgery ectasia. Additionally, genetic testing has been another way to determine postrefractive surgery ectasia risk.

CRST: How do you then present the rewards versus risks with patients?

Dr. Chu: Patient personality, their tolerance for stress and uncertainty, and their understanding of the limitations of the technology play a big part in how I approach presenting the risk versus reward. All these things come into play when we’re trying to help guide them to the right technology for them. The journey toward customizing the technology to the right patient includes assessing how they react to the risks and rewards of a treatment. With the right education before patients enter the office and, sometimes, multiple visits, the rewards of the procedure begin to overshadow the risks.

Dr. Heckman: It is important for patients to have a realistic understanding of both rewards and risks when deciding to proceed with treatment. Referring to scientific facts from the literature, especially results from FDA trials, is helpful to educate patients, as is sharing my own clinical experience. Both help to give patients a good understanding of the treatment option presented. When a patient understands both risk and reward, they then feel comfortable moving forward with treatment.

Dr. Schweitzer: Understanding how much of an impact a vision complaint or problem has on patients’ lives is key. I ask them to rank on a scale of 1 to 10 (10 being the worst) the impact the problem is having on their daily activities. That allows both me and the patient to put the problem in perspective and decide if it is worth them undergoing the procedure or intervening.

CRST: How do you balance keeping patients safe with becoming an early adopter of technology?

Dr. Chu: I think there’s a human factor to this. I always ask myself: “Is this technology something that I feel comfortable offering to a family member or a very close friend?” We’re in a very patient-centric profession. We don’t perform technological transactions—we perform human interactions.

My practice has been involved in more than 100 FDA clinical trials, and we are used to adopting new technologies successfully. Having the mindset that we are not experimenting on our fellow humans but using all the information possible to provide the best care and the most options to patients helps me balance keeping patients safe with offering new technologies.

Remembering that we’re dealing with other human beings and treating them with compassion has helped modulate that desire to try the latest and newest things.

Dr. Heckman: Safety is always top of mind in patient care, whether it is with new or longstanding technology. Understanding and evaluating for appropriate candidacy with the technology helps keep patients safe.

Dr. Loh: I typically like to first hear from my colleagues’ experiences and look at the clinical data. When I do adopt a new technology, I always first start treating the most appropriate patients to simplify the learning curve.

Dr. Schweitzer: For many of the technologies we use at our clinic, we were involved in the FDA clinical trials. This provides the opportunity to thoroughly evaluate the technologies in patients who are ideal candidates before they are introduced to the market. If we were not part of the clinical trials for a certain technology, I seek out colleagues who have already adopted the technology to gain insights and feedback. Finally, I seek out peer-reviewed literature to understand the technology’s safety data.

CRST: How do you keep yourself from being risk averse?

Dr. Chu: Being risk averse is a mindset. We are all appropriately cautious when we’re treating patients. The desire to push the field of ophthalmology forward in a careful and ethical manner is how I keep myself from being risk averse. I do as much information gathering as I can about a new technology, whether it’s from colleagues outside the country or others, and see if the technology fits within my skillset as a surgeon and the mindset of my practice.

Dr. Heckman: Staying educated and having a good clinical understanding of current and upcoming technologies helps me stay risk averse and feel comfortable recommending or prescribing treatment to appropriate patients.

Dr. Loh: I agree with Dr. Chu that it’s more of a mindset. If we don’t try new things and we don’t stay up with technology, we’re risking that our patients will not receive the best technology. For example, MIGS was not a category when I was in training, but when I saw the data and realized that it was helping patients and could provide a better quality of life, I knew that it was something I wanted to do. I think waiting too long or being too risk averse could potentially lead to not providing the best care for my patients, and this ultimately is what keeps me from being risk averse.

1. Ropeik D, Clay G. Risk! A practical guide for deciding what’s really safe and what’s really dangerous in the world around you. New York: N Y Houghton Mifflin, 2002.

2. McDonald MB, Barnett M, Gaddie IB, et al. Classification of presbyopia by severity. Ophthalmol Ther. 2022;11(1):1-11.

3. Waring GO 4th, Price FW Jr, Wirta D, et al. Safety and efficacy of AGN-190584 in individuals with presbyopia: the GEMINI 1 phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(4):363-371.