Upper blepharoplasty is one of the top 10 most requested facial cosmetic procedures. As an ophthalmologist, you are uniquely qualified to perform safe and effective surgery on the upper eyelid. Even better news, candidates for this procedure are already in your practice. Adding oculoplastic services to your practice’s offerings entails identifying interested patients and establishing the processes required for making this cosmetic service available to them.

IDENTIFYING INTERESTED PATIENTS

How do you introduce the option of cosmetic upper blepharoplasty to your patients? First, make them aware that your practice offers this surgery. There are several ways to go about this, including the following:

- Ensure written educational materials are available in the waiting area;

- Post a description of the service on your practice’s website;

- Mention cosmetic blepharoplasty on your practice’s social media accounts; and

- Instruct your workup technician to inform patients that drooping eyelids can be improved with cosmetic surgery. This may be a simple question such as, “You know we all get some drooping of the upper eyelid skin over time. Has this been a concern for you?”

There are many patients who have cosmetic concerns but who are reluctant to ask about this service or who are unaware that it is one you offer.

DIFFERENTIATING BETWEEN COSMETIC AND FUNCTIONAL CONCERNS

As people age, they can experience gravitational descent of the lid fold, protrusion of the medial upper lid fat pad, and loss of eyelid skin elasticity. Most of the people affected by these issues recognize and dislike the puffiness of their upper eyelids and the descent of the skin fold toward the eyelashes. Initially, this droopiness is a cosmetic concern, but it may become a functional impairment as it progresses.

Blepharoplasty may be covered by insurance if patients have functional impairment. It is important to distinguish between these individuals and those for whom blepharoplasty would be a cosmetic—and therefore a cash-pay—procedure. The surgical technique may be similar in both scenarios. Patients undergoing cosmetic blepharoplasty, however, will have different expectations of the process and the goals of surgery.

ESTABLISHING A COSMETIC OFFERING

Scheduling and billing. If upper blepharoplasty will be your first foray into cosmetic surgery, think through how these patients will be scheduled and develop a plan for cash-pay surgery. If surgery will occur in a hospital setting or at an ambulatory surgery center, cash-pay billing must be arranged at those sites, and your practice must be able to quote costs to patients before surgery. If surgery will be performed in the office (ie, a procedure area), decide in advance if the technical costs of the room time and materials will be included in the price of the procedure or if a separate quote will be given for the site of service. Your practice must also create a policy for what the cost of the procedure covers. Will the surgeon fee cover any additional procedures, medications, or follow-up care, or will these be billed separately?

The patient evaluation. The evaluation for cosmetic blepharoplasty begins with photography. Documenting a patient’s preoperative condition is valuable for surgical planning, preoperative discussions, and postoperative comparisons. In my experience, patients never remember how droopy their upper eyelid was before surgery until they review their preoperative photographs.

The patient history should include a list of previous periocular procedures, prior ocular surgery (particularly recent corneal refractive surgery), medical conditions that could affect the site of surgery or impair healing, and ocular history such as dry eye disease (DED). It can be helpful to discuss with patients their desired final eyelid shape, particularly if they have genetic variations in the eyelid crease or fold. Before surgery, it is important to discuss with them the position of the eyebrow and the limitations that it may place on the postoperative outcome.

Physical examination. Look at the vertical palpebral fissure, the distance from the margin of the upper lid to the central corneal reflex, and the distance from the upper eyelid margin to the lid crease (margin fold distance). Determine if there is preexisting lagophthalmos or lower eyelid retraction. Abnormal puffiness of the eyelids may be an early indication of thyroid eye disease.

Evaluate the ocular surface and tear film to assess the potential for postoperative problems with ocular surface exposure. Treat meibomian gland dysfunction and DED before surgery.

Surgical planning. The surgical plan includes potential tissue removal or repositioning. Excess skin at the upper eyelid may be removed, and excess fat in the nasal fat pad may be removed or repositioned if there are other deficits in the eyelid contour. The orbicularis oculi muscle may be partially removed to reduce lid bulk or left in place to help preserve the strength of the blink in patients with DED.

The sum of eyelid skin left in place in the upper eyelid generally should be around 20 mm. Removing nasal fat is typically helpful, but central upper lid fat should be preserved unless it is unusually excessive. The lacrimal gland may descend into the lateral aspect of the upper eyelid and occasionally requires resuspension back into the lacrimal gland fossa. In some patients, judicious debulking of the subbrow fat pad (retro–obicularis oculi fat) may reduce the fullness of the temporal upper eyelid.

Creating symmetrical upper eyelid folds is an important cosmetic component of upper blepharoplasty surgery. Re-formation of the eyelid crease and fold with anchoring sutures may be necessary at the time of skin incision closure. (For more on the surgical technique for blepharoplasty, see the sidebar below.)

Surgical Techniques for Upper Blepharoplasty

Several approaches to creating the upper blepharoplasty incision are appropriate, but serious complications can be avoided by following six basic guidelines.

NO. 1: MARKING THE INCISION

A fine-tipped surgical marking pen is used to mark the incision and areas of fat excision, addition, or transposition. The inferior border of the blepharoplasty incision is typically placed on the eyelid crease if it has not been distorted by previous surgery and is not asymmetric with the other side. The presence of asymmetric creases should be discussed with the patient during the office evaluation. If surgical correction of the asymmetry is desired, the lid crease that is closest to the natural position is typically used as the guide. The eyelid crease is often located 8 mm above the lash line. In White patients, the central portion of the crease is highest; the temporal and nasal ends are lower. In Asian patients, the crease is relatively straight.

NO. 2: PLANNING THE INCISION

The incision should extend no closer than 5 mm vertically from the superior punctum and, in general, should not extend medial to a line drawn vertically through the punctum. Carrying the incision too far medially can result in a cicatricial band or webbing. The temporal extent of the incision should not extend lateral to a line drawn vertically through the tail of the eyebrow. The superior border of the incision should pass no closer than 10 mm from the inferior border of the eyebrow. This represents the approximate point of transition between the thicker skin of the eyebrow and the thinner skin of the eyelid. Incorporating brow skin into the blepharoplasty closure can cause brow ptosis and an unappealing cosmetic result. This is because of differences in skin texture and thickness when the thin skin of the eyelid is aligned with the thicker subbrow skin.

NO. 3: ESTIMATING THE SKIN TO BE REMOVED

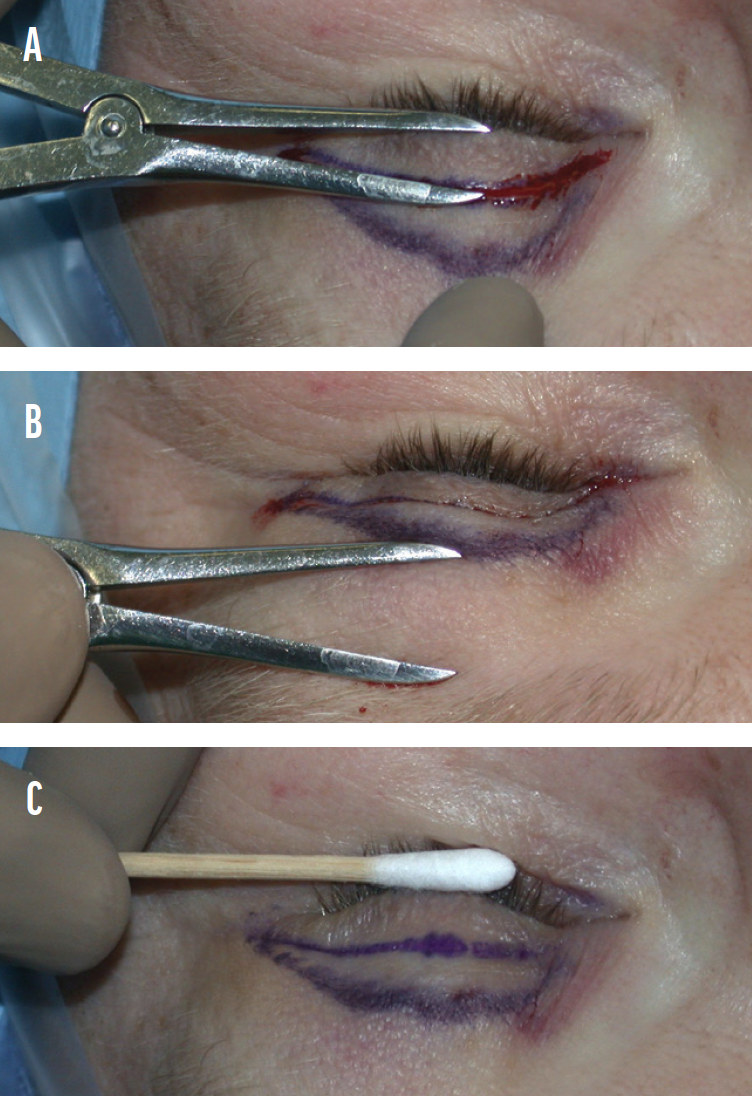

Various techniques for estimating the amount of eyelid skin to be removed can be used. For beginning surgeons, measuring the incision locations with caliper confirmation is recommended (Figure 1). The patient is asked to gently close their eyes while supine. The eyelid crease is then marked. Next, a caliper or ruler is used to measure the distance from the eyelid margin to the lid crease. If a minimum of 20 mm of skin total should remain between the eyelid margin and the inferior brow cilia, the eyelid crease measurement is subtracted from 20 mm to determine how much skin is left below the brow. If this guideline is observed, lagophthalmos and the associated ocular surface exposure can usually be avoided. Initial eyelid markings are performed before a local anesthetic is administered.

Figure 1. The distance from the lashes to the eyelid crease is measured (A). The skin to be left intact below the eyebrow is measured (B). At least 20 mm of intact skin must be left in the eyelid. The cental area between the lines may be removed (C).

NO. 4: DELIVERING ANESTHESIA

Usually, 1% or 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 and 10 units of hyaluronidase per 10 mL of a local anesthetic are injected subcutaneously in the central upper lid using a 30-gauge needle. Bupivacaine 0.75% may be added in a 50:50 mixture with the lidocaine to prolong the effect of anesthesia. A bleb containing approximately 2 mL of anesthetic is made below the orbicularis oculi muscle in the central region of the upper lid.

Injection trauma to the orbicularis oculi muscle is avoided when possible to minimize preoperative hematoma formation from the local injection. The more times that the needle is passed through the tissue, the more opportunities there are to hit a vessel. Delivering a single injection and allowing the anesthetic time to spread through the lid help to minimize the formation of injection hematoma. Digital massage can help to distribute anesthetic medially and laterally throughout the upper eyelid. The inclusion of hyaluronidase allows a single injection site to be used because this enzyme increases the diffusion of anesthetic throughout the tissues. This technique of administering local anesthesia avoids the need for multiple punctures in the eyelid skin, thus reducing localized tissue trauma and the likelihood of ecchymosis or hematoma formation.

NO. 5: PREPPING THE PATIENT

The patient is prepped and draped in the usual sterile fashion. The preoperative markings might have faded or been partially removed during skin prep. If so, re-marking should occur at this time. Even if the markings do not require replacement, it is good practice to double-check the accuracy of the preoperative measurements using calipers or a ruler.

NO. 6: PERFORMING THE PROCEDURE

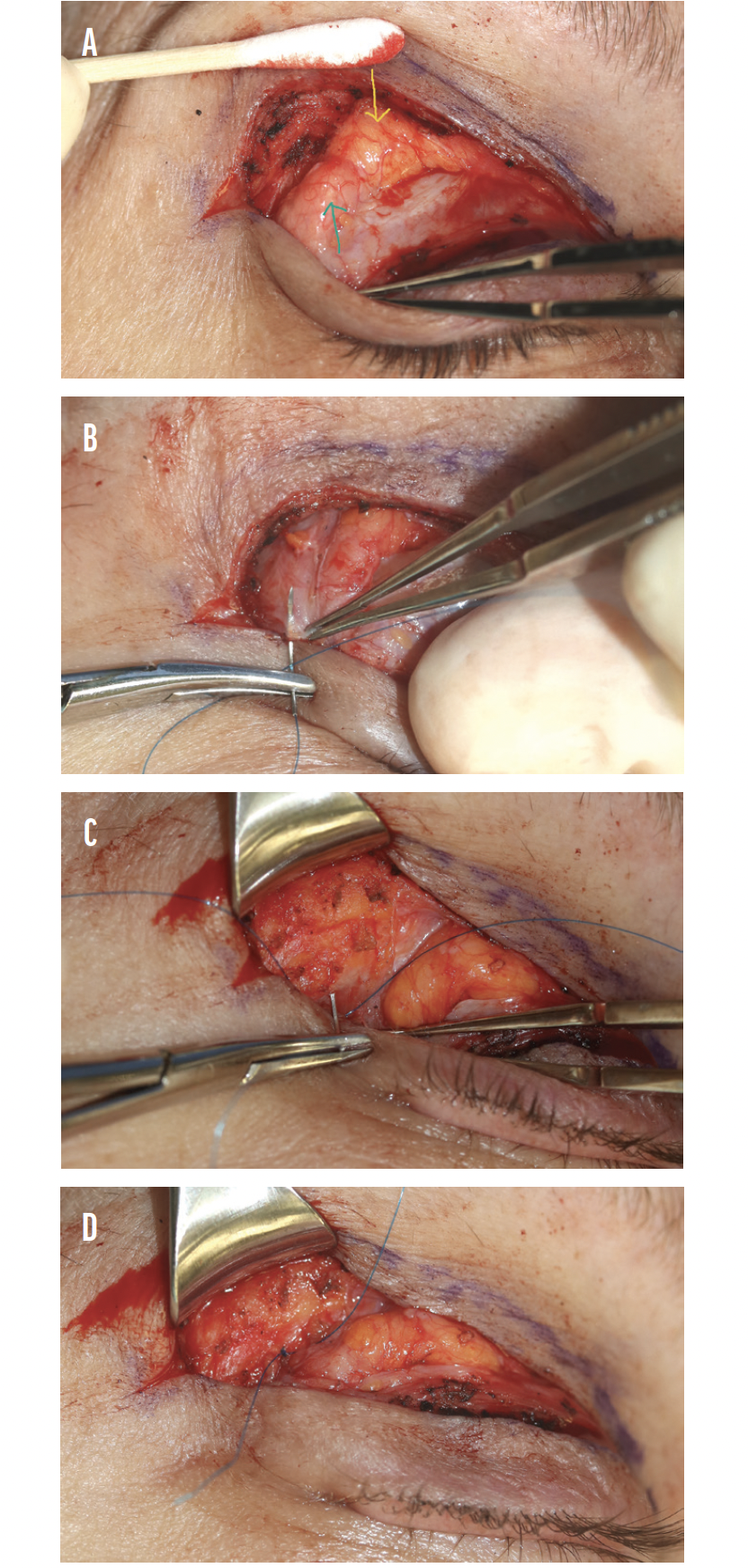

Figures 2 and 3 depict several steps of the procedure. The incision is made with a No. 15 Bard-Parker blade. After the incision is complete, a toothed forceps (usually 0.5- or 0.3-mm) is used to elevate the temporal tip of the skin ellipse. The skin flap may be dissected with Wescott scissors. A skin-only or skin-muscle flap may be removed. The removal of the orbicularis oculi muscle during upper blepharoplasty is based on the surgeon’s preference, but sulcus contour should be considered, as it is during fat excision. Some surgeons prefer to leave behind the orbicularis oculi muscle in patients with dry eye disease to improve blink strength. For a skin-only flap, traction is kept on the skin to help separate it from the underlying orbicularis oculi muscle. Both dissection methods take place in the plane anterior to the orbital septum.

Figure 2. The yellow and green arrows point to central fat and prolapsed lacrimal gland, respectively (A). A polypropolene suture is used to imbricate the capsule of the lacrimal gland (B). The polypropolene suture is passed through the internal aspect of the lateral orbital rim (C). The suture is tied down, repositing the lacrimal galnd upward into the lacrimal gland fossa (D).

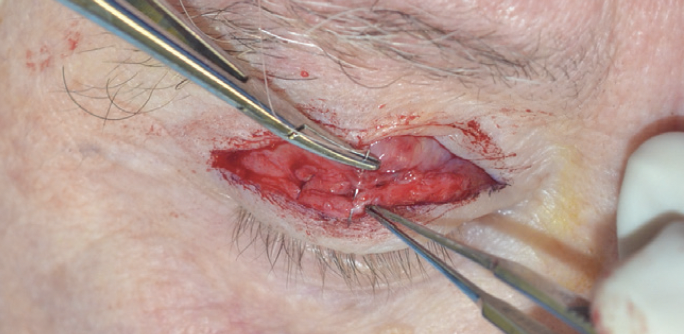

Figure 3. The resorbable suture goes from orbicularis to levator aponeurosis to reform the lid crease.

Fat removal. Once the flap has been excised, the orbital septum will be visible. When fat removal is desired, the septum is divided to expose the preaponeurotic fat pads. It is recommended that novice surgeons first incise the septum in the region of the nasal fat pad to reduce the risk of trauma to the levator aponeurosis. Once the proper tissue plane has been identified, the incision can be extended laterally using Wescott scissors.

The capsule of the fat is opened in areas where fat removal is desired. Nasal fat is white; central fat is yellow. The fat pad is grasped with forceps and carefully elevated from the underlying levator aponeurosis to which it is loosely adherent. While superior anterior traction is placed on the septum and preaponeurotic fat, a cotton-tipped applicator can be used to facilitate the separation of the fat from the underlying levator aponeurosis. The fat is trimmed with cautery. If excessive central fat is present, a small amount may be resected conservatively. This should be performed with great caution because the overresection of fat produces a hollow or skeletal look in the eyelid-sulcus region. Gentle pressure may be applied to the globe through the eyelid to help prolapse orbital fat into the surgical field. This adipose tissue is quite vascular; if a laser or cutting cautery tip is not being used for excision, it is recommended that the fat be clamped or fixated and cauterized before or after excision. This will reduce the chance that a hemorrhage will develop postoperatively.

Fullness and contour irregularity of the lateral brow are then addressed. A pronounced appearance to the lateral brow may be caused by a prominent underlying frontal bone or by relative enlargement or descent of the brow fat pad. This fat pad, usually referred to as retro-orbicularis oculi fat or ROOF, tends to migrate inferiorly owing to a loss of support and natural attenuation. Many patients are reluctant to undergo reduction of the bony orbital rim. Conservative contouring of the ROOF complex, however, may be readily performed with cautery, scissors, or laser ablation to achieve an appealing aesthetic result.

Wound closure. There are many options for wound closure. If the lid crease is not to be re-formed, then an interrupted or running 6-0 or 7-0 permanent monofilament suture (eg, nylon or polypropylene) may be used. Some surgeons favor a 6-0 plain gut suture because its removal is not necessary. A small cutting needle (P-1 or PC-1 [Ethicon]) is sufficient, but some surgeons prefer to use a taper-cut needle that may reduce trauma to the tissues. In a simple closure, sutures are passed from skin edge to skin edge. Care should be taken to ensure that the wound is properly aligned across its entire extent. Due to the curvilinear shape of the incision, the vectors of force vary across the width of the wound. If interrupted sutures are used, the wound should be aligned by initially placing cardinal sutures centrally, nasally, and temporally. Care should be taken to ensure wound edge eversion regardless of the method employed.

If the lid crease is to be changed from its original location, if the surgeon desires a more distinct lid crease, or if the levator muscle is moved during surgery, additional steps may be taken to create a lid crease at the time of wound closure. If a lid crease is to be created, an interrupted 6-0 undyed P-1 polyglactin suture (Vicryl, Ethicon) is placed through subcutaneous tissue on the inferior margin of the wound. The needle pass should engage the levator aponeurosis at the superior tarsal border and then transverse the orbicularis oculi muscle on the superior border of the wound. Three such interrupted sutures are placed—one in the nasal portion of the lid, one in the central portion, and one in the temporal portion. The remainder of the wound between these sutures is closed skin edge to skin edge with permanent or absorbable suture material, depending on the surgeon’s preference. Alternatively, the surgeon can incorporate the levator aponeurosis into the sutures that close the skin at predetermined areas of the incision. The suture passes through skin and orbicularis oculi, takes a superficial bite of the levator aponeurosis along the superior border of the tarsus, and then takes a full-thickness bite through the skin and orbicularis oculi of the opposite side of the wound. These lid crease reformation sutures can be placed with either a running or interrupted closure using the skin suture. The suture pass that catches the deeper tissue is typically spaced out at three or four locations in the closure.

Conclusion of the procedure and postoperative course. An ophthalmic ointment is placed on the eyelid incisions, followed by sponges soaked in iced saline, a bag of frozen peas, or crushed ice. Ophthalmic antibiotic-steroid ointment is placed along the incision line and may also be placed in the eyes to enhance patient comfort.

Patients are instructed to apply ointment to the incision twice daily until the sutures dissolve or are removed. The ophthalmic ointment may be used in the eye thereafter as needed for comfort. The patient should be instructed to avoid heavy lifting and bending for a week and to call the office if pain or bleeding occurs.

CONCLUSION

The basic surgical steps of functional upper blepharoplasty are often acquired during residency. Honing the techniques to evaluate and alter the nuances of cosmetic blepharoplasty may require the attainment of additional skills. Reading about technique is useful, but in-person training at a surgical dissection course and operating with a mentor are invaluable and the most efficient ways of acquiring these skills.