Overcoming Challenges in Saudi Arabia

Adel AlAkeely, MBBS; Halah Bin Helayel, MBBS; and Rizwan Malik, MBChB, PhD, FRCOphth

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a growing country; its population is expected to exceed 35 million this year.1 It is the 12th largest country globally and consists of 13 administrative regions, including the capital, Riyadh.

IDENTIFYING THE CHALLENGES

A majority (72%) of the population is between 15 and 64 years of age.2 The most common cause of blindness in the Kingdom is cataract, followed by diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma.3-5 Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and congenital glaucoma are significant causes of childhood blindness.6 Two challenges decrease patient access to eye care.

Challenge No. 1: A shortage of providers. There is a shortage of ophthalmologists in the Kingdom. In a 2014 survey,7 the ophthalmologist-to-population ratio was 1:43,000. The Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (the medical commission responsible for training and licensure) responded to the shortage by increasing the number of students enrolled in its accredited ophthalmology training programs by approximately 25% and accredited more programs to meet demand. Prior to that time, there were only three accredited residency programs.8 Now, there are eight accredited training programs in the Kingdom.

Challenge No. 2: Systemic problems. Saudi Arabia currently lacks a definitive primary health care system; eye care consists mainly of secondary and tertiary eye hospitals. Complex and advanced cases are usually referred to tertiary eye centers, mostly to King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital (KKESH) in Riyadh. The absence of a defined primary care service limits patient access to eye care and often leads to the late presentation of patients with diseases such as glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy.

IMPROVING ACCESS

To improve access to eye care, KKESH has employed several strategies. These include launching screening campaigns in rural parts of the Kingdom, increasing resources at peripheral eye units, developing a structured social media campaign to raise public awareness about blinding eye diseases, and investing in AI protocols for screening for diabetic retinopathy and in telemedicine for ROP screening.

Screening programs. In collaboration with the Ministry of Health (MOH), KKESH conducts screening campaigns for glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy in villages and small or peripheral cities.9 The outreach programs undertaken by KKESH also provide support for specialist services such as retinal and oculoplastic care in Jeddah and Madinah by sending surgeons to these regions to help reduce the waitlists (Figure 1).10 In November 2020, eye donation month, KKESH launched a program in which keratoplasties were performed every weekend, and concurrent media coverage was provided to inform the local community about organ donation.

Figure 1. KKESH volunteer surgeons and staff perform cataract surgery during the Ibsar Sa’em Cataract Campaign in Saudi Arabia’s Qassim Province in May 2019.

A number of other KKESH-sponsored programs aim to improve access to eye care and reduce preventable vision loss. A major breakthrough for pediatric eye care is the national ROP telescreening program established by MOH hospitals in collaboration with KKESH that covers all level-three neonatal intensive care units in the Kingdom. The goal is to prevent 400 cases of ROP-related blindness annually.11 Longer-term plans include developing a more defined primary care structure, with optometrists involved in screening and referrals for management.

Given the high rate of consanguineous marriages in the region, the introduction of premarital screening and counseling programs for certain genetic disorders such as congenital glaucoma is expected to be beneficial and cost-effective (Figure 2).12 Saudi Arabia has the highest prevalence of congenital glaucoma in the world at one in 2,500 inhabitants.13

Figure 2. The genetic counseling clinic at KKESH for families with children who have congenital glaucoma.

Social media. The MOH and tertiary eye hospitals such as KKESH have relied heavily on social media to increase public awareness of eye diseases. Through its Twitter and Snapchat accounts, the KKESH media department releases educational resources and tools to promote community awareness, teach visually impaired patients how to use computers, and highlight inspiring stories. One story described a teacher who provided daily online instruction of his classes during his recent stay in the hospital after eye surgery.14

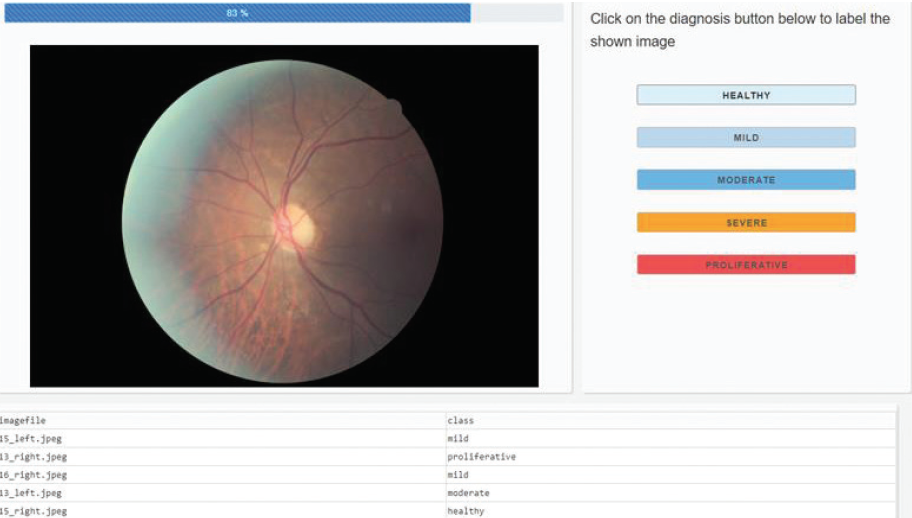

AI protocols and telemedicine. In the long term, it is expected that telemedicine and AI will play crucial roles in facilitating patient access to eye care and reducing the cost and burden of eye diseases, particularly diabetic retinopathy.15 The implementation of commercially available AI models is underway, and the results thus far are promising (Figure 3).16 Initial studies indicate that these models have high sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing and grading diabetic retinopathy.17,18

Figure 3. An AI model (not yet commercially available) built through a collaboration between KKESH and Lean business services and used for diabetic retinopathy screening.

Figures 1–3 courtesy of Rizwan Malik, MBChB, PhD, FRCOphth

1. Saudi Arabia population. Worldometer. Accessed December 7, 2020. www.worldometers.info/world-population/saudi-arabia-population

2. General Authority for Statistics. Demography survey. Accessed December 7, 2020. www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/en-demographic-research-2016_2.pdf

3. Al-Ghamdi AS. Adults visual impairment and blindness – an overview of prevalence and causes in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2019;33(4):374-381.

4. Al‐Rubeaan K, Abu El‐Asrar AM, Youssef AM, et al. Diabetic retinopathy and its risk factors in a society with a type 2 diabetes epidemic: a Saudi National Diabetes Registry-based study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(2):e140-147.

5. Khandekar R, Chauhan D, Yasir ZH, Al-Zobidi M, Judaibi R, Edward DP. The prevalence and determinants of glaucoma among 40 years and older Saudi residents in the Riyadh Governorate (except the Capital) – a community based survey. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2019;33(4):332-337.

6. Tabbara KF, El-Sheikh HF, Shawaf SS. Pattern of childhood blindness at a referral center in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25(1):18-21.

7. Al Motowa S, Khandekar R, Al-Towerki A. Resources for eye care at secondary and tertiary level government institutions in Saudi Arabia. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21:142-146.

8. Statistics of postgraduate training programs. Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. December 7, 2020. www.scfhs.org.sa/MESPS/Statistics/Pages/default.aspx

9. Ministry of Health. Glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy clinics launched at Al-Quwayiyah and Huraymala. March 25, 2020. Accessed December 7, 2020. www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2020-03-25-003.aspx

10. King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital. The conclusion of “Ebsar Saem” campaign. Accessed December 7, 2020. /www.kkesh.med.sa/en-us/Media-Center/In-News/KKESH-News/pageindex9551/2

11. Ministry of Health. Health Minister Launches Retinopathy of Prematurity National Program. March 14, 2019. Accessed December 7, 2020.www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/news-2019-03-14-009.aspx

12. Malik R, Khandekar R, Boodhna T, et al. Eradicating primary congenital glaucoma from Saudi Arabia: the case for a national screening program. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2017;31(4):247-249.

13. Alanazi FF, Song JC, Mousa A, et al. Primary and secondary congenital glaucoma: baseline features from a registry at King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155(5):882-889.

14. @KKESHKSA. You make a mistake when you think that such stories are found only in novels or cinema movies. Behind this picture … a story. October 10, 2020. Accessed December 7, 2020. /twitter.com/KKESHKSA/status/1314931473829580801?s=20

15. Xie Y, Nguyen QD, Hamzah H, et al. Artificial intelligence for teleophthalmology-based diabetic retinopathy screening in a national programme: an economic analysis modelling study. The Lancet Digital Health. 2020;2(5):e240-e249.

16. AlAjmi M, Al Akeely A, Al Subaie H, et al. Pilot: a validation study of a novel, fully-automated, disease grading and clinical decision support system for screening and telemedicine-based diagnosis of the sight threatening condition of diabetic retinopathy (DR). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61(7):2009-2009.

17. Bhaskaranand M, Ramachandra C, Bhat S, et al. The value of automated diabetic retinopathy screening with the EyeArt System: a study of more than 100,000 consecutive encounters from people with diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21(11):635-643.

18. Gulshan V, Rajan RP, Widner K, et al. Performance of a deep-learning algorithm vs manual grading for detecting diabetic retinopathy in India. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(9):987-993.

Adhering to Chilean Clinical Guidelines Can Improve Access

By Andreas Di-Luciano, MD, and Valentina Berrios, MD

Santiago, Chile

In Chile, the introduction of the Explicit Health Guarantees Regime (GES) in 2005 significantly improved access to ophthalmologic care in our country. This system prioritizes care for patients at increased risk of severe vision impairment from five highly prevalent ophthalmologic pathologies (cataract, diabetic retinopathy, retinal detachment, refractive visual problems in people over 65 years of age, and ocular trauma). For many patients, wait times for diagnosing and treating these pathologies have decreased dramatically because of the GES initiatives.

The GES’s clinical guidelines and care protocols, devised by Chile’s health authority in collaboration with scientific societies, are based on existing scientific evidence and established quality standards. These measures have improved access to ophthalmologic care in our country; however, we continue to face difficulty providing care to certain populations. This is even more evident in the time of COVID-19.1

BACKGROUND

Access to health care in Chile is highly centralized in Santiago, the capital city. Eye care practitioners are located throughout Chile, but patients oftentimes must travel to the capital to receive care from a specialist or undergo a modern diagnostic test. Further, Chile has a low number of ophthalmologists per million inhabitants. That number is increasing every year but remains inadequate to meet the needs of public eye care.

COVID-19 has accentuated the gap in access to care, which is mainly caused by a decrease in the number of patients who can attend their appointments. Adaptations to care, including the adoption of telemedicine, have become necessary to provide uninterrupted eye care to patients who need it most.

THREE PILLARS OF CARE

We follow the recommendations of the World Health Organization, the Chilean health system, and scientific communities worldwide. We have based our care model during the current pandemic on three pillars: COVID-19 awareness, hospital resources, and surgical care.

Awareness. We prioritize care according to the prevalence and incidence rate of COVID-19 and follow all current quarantine mandates in order to keep both our staff and our patients safe. We constantly update our policies and take the necessary precautions in terms of materials and health and human resources.

We screen staff and patients for signs of COVID-19 when they first enter the practice, and we have developed operational testing policies, including the mandatory use of the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test for all patients scheduled for corneal transplantation and any surgery with general anesthesia. This test is not required for cataract and refractive surgery patients, but we rule out any suspicion of infection or risk of virus transmission before surgery.2-4

Hospital resources. We keep track of the open number of beds, intensive care services, diagnostic imaging capabilities, and clinical laboratory testing at our patient care facility. In some cases, we have extended services for elective surgery to the weekends, which allows us to space out our consultations and appointments and increase adherence to our safety protocols.

We follow strict cleaning protocols and reinforce their use before, during, and after all patient appointments. Likewise, we continue to revise our timetables and schedules inside and outside the OR to increase efficiency. We allocate time for specific types of surgery in blocks and group cases according to the similarity of the procedures to be performed to increase efficiency and maximize workflow.2,3 We also schedule appointments according to priority. This all helps to maximize patient access to care.

When patients cancel or postpone their appointments, we immediately rearrange our schedule and consider coordinating with other supportive surgical centers in the hopes of generating more appointment slots for patients who are waiting for care.

Before this process is adopted by other centers, we suggest establishing a good amount of surgical supplies, support from other eye care providers, and adequate local inventory to anticipate shortages in other areas of care.3 The key to success in multidisciplinary coverage is ensuring coordination among surgeons, anesthetists, nurses, engineers, cleaning staff, and others.2,3

Surgical care. The prioritization of certain surgical procedures is used to guide our plan and increase access to patient care. For example, emergency cataract surgery takes priority over scheduled refractive surgery procedures. Explaining this to patients helps to decrease presurgical anxiety. Again, we consider rescheduling patients who canceled or postponed their appointments whenever we have an open slot in our schedule, while taking into account all other points of availability and local capacity.

We discuss the use of personal protective equipment protocols with patients before their surgery is scheduled. We ask them to remove their masks once they enter the OR and not to speak during the asepsis process. Thereafter, it is okay to resume verbal communication with the staff.2-4

CONCLUSION

Patient access to eye care in Chile continues to improve. Over the years, and especially in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we have devised a three-pillar system to ensure that we can maximize the volume of patients we are able to treat.

1. Meza P. Ges en oftalmología. Ophthalmological pathologies at GES. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes. 2010;21:865-873.

2. American College of Surgeons. Local resumption of elective surgery guidance. April 17, 2020. Accessed December 7, 2020. www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/resuming-elective-surgery

3. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Accessed December 7, 2020. www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

4. Kohnen T. The new normal for cataract and refractive surgery due to COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2). J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020;46(6):809-810.

5. American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. Clinical education. April 28, 2020. Accessed December 7, 2020. ascrs.org/clinical-education

Egypt’s Outreach Programs Focus on Rural Eye Care Services

Mohamed Hosny, MD, PhD

Cairo, Egypt

Health care has always been a patchy business in developing countries such as Egypt, where I practice. Complex and state-of-the-art health care is available in large cities such as Cairo that have tertiary centers but not in the majority of the country, which consists of small towns and villages. This situation has been the norm for a long time, and patients requiring advanced procedures travel hundreds of miles for treatment.

Over the past 3 decades, university departments and renowned private centers have begun to establish satellite locations in rural areas. This trend is positive, but it is inadequate to meet the demand for eye care. Many patients with curable vision-limiting disease remain untreated in small villages. As these individuals become increasingly disabled, the burden on the micro- and macroeconomy grows.

COVID-19 has dramatically worsened the situation. The economic downturn has decreased patients’ ability to travel to tertiary centers. Partial lockdowns have posed logistical hurdles as well.

In an attempt to alleviate the impact that this pandemic has had on rural eye care services, premium university ophthalmology departments and upscale private specialized eye hospitals have intensified their outreach programs (Figure 4). Medical convoys with mobile clinics travel to rural areas, and screening examinations are conducted for a whole sector or age group in randomly selected poor rural villages. These efforts have sparked contributions from local private sector corporations, which have organized the transportation of patients to tertiary centers for surgery.

Figure 4. A patient waits for her examination at a mobile clinic (A). Patients are examined at the mobile clinic (B, C).

Courtesy of Mohamed Hosny, MD, PhD

To date, outreach efforts have not had a significant impact on the delivery of eye care to rural communities. The mobile surgical ORs, for example, require a huge boost in funding. Additionally, the Egyptian government requires that all patients undergo polymerase chain reaction screening before being admitted to a university hospital. The cost and limited availability of testing have caused many university hospitals to decrease their intake of eye surgery patients dramatically.

Nevertheless, it is to be hoped these systems will remain in place after the pandemic. At that time, they may help to increase eye care services in rural Egypt.

The Private Sector Plays a Fundamental Role in Eye Care in Algeria

Sihem Lazreg, MD, PhD

Algiers, Algeria

Eye care in Algeria, where I practice, is similar to that in the majority of North African countries. In these health care systems, primary medical insurance services are provided to all citizens. The incorporation of primary, secondary, and tertiary referral ophthalmology centers in the health care systems ensures that almost every citizen can obtain care adequately. The rural areas, typically the most underserved, have only minimal requirements to treat some ocular emergencies at the primary centers. Most emergencies are referred to the secondary and tertiary centers.

The private sector in ophthalmology plays a crucial and fundamental role in vision and eye care in Algeria. Private practices are found in abundance in all cities, provinces, and regions of the country. These centers possess all the basic and advanced diagnostic and therapeutic modalities as well as ORs to provide the full range of ophthalmic care exactly as that provided at governmental and insurance centers. Pricing at private practices is reasonable and compatible with the standard of living in this country. This kind of service reduces the burden on the National Health Service, and as a result, patients can obtain care more quickly in both kinds of institutions.

The National Health Service covers any basic school-aged, glaucoma, and other screenings. The waiting list for cataract surgery, for example, is minimal.

In Algeria, there are approximately 40 ophthalmologists per million residents, which is one of the highest ratios in Africa.1 It reflects the adequacy of ophthalmology services in my country.

1. Resnikoff S, Lansingh VC, Washburn L, et al. Estimated number of ophthalmologists worldwide (International Council of Ophthalmology update): will we meet the needs? Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:588-592.

Eye Care Access in Morocco

Imane Tarib, MD

Rabat, Morocco

My years of training in Morocco included 2 years of internship and 6 years of residency at the civil and military university hospitals of Rabat. These tertiary institutions are regarded highly and considered to be among the best health care structures in the kingdom.

BACKGROUND

The public health care sector in Morocco consists of several networks. Patients obtain their basic health care services at local dispensaries or centers, where they are seen by general medicine physicians. If patients require the care of a specialist, those services are provided by local, regional, and provincial hospitals, in that order. If advanced treatment and care beyond hospital care is required, patients then visit the university structures, which are otherwise known as tertiary health care structures.

Ophthalmology is considered highly specialized, and eye care is mainly provided at the tertiary care level. More often than not, surgical procedures are performed only at this level of the health care system.

During my time in Morocco’s public hospitals, long wait times for all types of appointments, including initial consultations, follow-up appointments, imaging, and surgery, seemed unavoidable. For most patients, waiting many months to be seen by an ophthalmologist is typical, as is waiting for surgery.

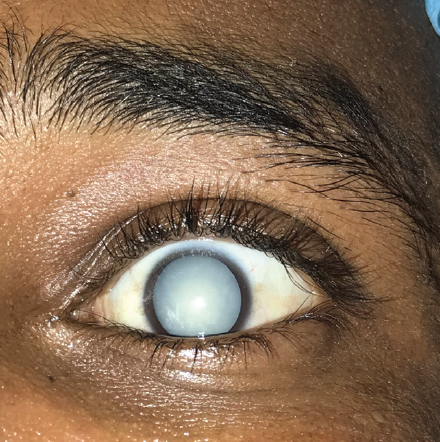

It is alarming but common for patients to present with advanced disease in Morocco. Rock-hard cataracts are not rare (Figure 5), and extracapsular cataract extraction (Figure 6) is often required. In response, many ophthalmologists organize regular mission trips to reduce the burden of advanced eye disease on our health care system. Most of these trips focus on screening patients for dense cataracts and advanced diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma (Figure 7). These conditions are especially prevalent in the mountainous regions of our country, where access to health care is scarce.

Figure 5. A rock-hard cataract.

Figure 6. A cataract removed with an extracapsular extraction technique.

Figure 7. Dr. Tarib screens a patient during a mission trip.

Figures 5–7 courtesy of Imane Tarib, MD

EARLY ACCESS TO CARE

During my residency training, I became fascinated by the hidden dimensions of early access to eye care. Factors in patient access to care extend far beyond the health system, insurance, and hospital infrastructure. It starts with education. Some patients are not aware that conditions such as cataract are treatable. Even when they are aware, certain superstitions and religious beliefs prevent some of them from seeking the proper treatment. I have seen patients refuse an IOL because they believe they will not be accepted by God if they die with a foreign body in their eye.

Health care is not provided exclusively by the public sector in Morocco. In fact, the private sector decreases the burden on overcrowded public hospitals.

From private practices owned by a solo practitioner to group clinics, patients see the private health care sector as their best option when they cannot wait for public health care and when they prefer state-of-the-art technology. It is only an option, however, for those who can afford it.

Furthermore, the private health care sector is the hub for highly specialized and elective procedures, including premium cataract surgery, refractive surgery, and oculoplastics. Most of these procedures are not available at the public sector hospitals.

CONCLUSION

The division of health care into the public and private settings in Morocco may be sufficient for now. With long wait times for appointments, follow-up appointments, and surgery, however, and the backlog of patients from COVID-19 restrictions, a private-public partnership, just like in business, may be necessary to provide quality and timely eye care to all those who need it.

Keratoconus Screening in Schools

Claudio Trindade, MD, PhD

Belo Horizonte, Brazil

The treatment of keratoconus changed dramatically with the development of CXL. The course of the disease became more manageable, leading to a new mindset that advocates the proactive detection of early signs of the disease.

Scheimpflug-based corneal tomography is another major step forward. Fast, low-cost, easy to perform, and noncontact—this technology can detect the early signs of keratoconus, even before clinical manifestation.

Despite these advances in treatment and detection, ophthalmologists still deal with damage from late diagnoses. A recent study by Chan et al found an alarming 1.2% prevalence of keratoconus in 1,259 participants in Western Australia who were 20 years of age.1 With these results in mind, my colleagues and I launched a large-scale keratoconus screening program in Belo Horizonte, the sixth-largest city in Brazil (population, approximately 3 million). The goal of the Ceratocone 2020 program is to examine the eyes of every student enrolled in public school who is 7 to 17 years of age.

Through the program, each school district (N = 13) received one Pentacam (Oculus Optikgeräte), which was installed in the main school of the district. A total of 190,000 examinations are expected to be performed annually. Examinations will take place inside the schools before each academic semester begins.

The program was developed in partnership with a local technology startup, and it uses AI to analyze the data and detect suspicious findings. Students with suspected keratoconus will immediately be referred to a corneal specialist so that treatment can be initiated.

The Ceratocone 2020 program was scheduled to commence in August 2020 but was postponed to August 2021 because of restrictions imposed by COVID-19. We believe that this program’s initiation will help increase access to care for school-aged patients who have identifiable signs of keratoconus.

1. Chan E, Chong EW, Lingham G, et al. Prevalence of keratoconus based on Scheimpflug imaging: The Raine Study. Ophthalmology. August 26, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.08.020