Uncontrolled Lens Insertion at the End of Otherwise Uncomplicated Phacoemulsification

Kourtney Houser, MD

An important lesson we surgeons all learn is to maintain focus throughout every step of every surgery. As tempting as it is to exhale and relax after saving an errant capsulorhexis or removing the last quadrant of a brunescent cataract, we must maintain focus so that we can respond to unexpected events quickly and methodically. The more cases we do, the more complications we see. Complications may become less disruptive over time, but challenges can occur at any step of any case. By remaining vigilant until the drape comes off, we increase the likelihood that we will recognize in a timely fashion subtle findings that may herald difficulty during subsequent steps.

A routine cataract surgery case that I staffed highlights the importance of maintaining unwavering focus.

CASE EXAMPLE: UNDER PRESSURE

Through wound construction, capsulotomy, nuclear disassembly, cortical removal, and capsular polishing, no problem arose. The well-supported capsular bag was filled with a cohesive OVD. The chosen, verified, preloaded one-piece acrylic IOL was prepared in the usual method by an experienced surgical technician.

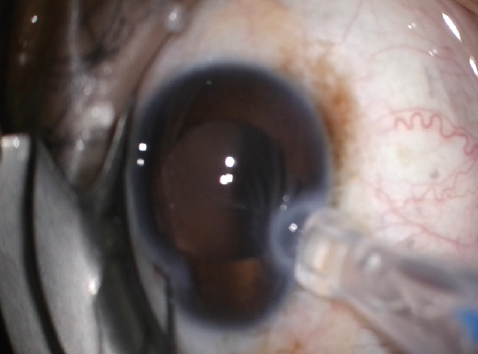

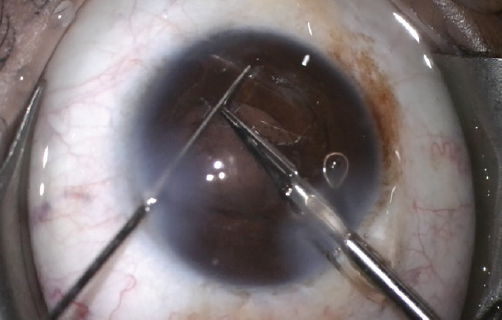

A Sinskey hook was used to assist with globe stabilization during insertion of the IOL. Greater than average force was required to insert the tip of the lens injector into the wound. This excessive force resulted in corneal striae, nasal displacement of the globe, and difficult visualization (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nasal displacement of the globe with corneal striae, leading to a decreased red reflex and difficult visualization.

During injection of the IOL with the preloaded delivery system, resistance was encountered in the plunger mechanism. Maintaining gentle, even pressure on the plunger failed to allow complete insertion of the lens. As increased force was applied, there was a catch followed by a rapid release with quick movement of the IOL into the capsular bag. This forceful insertion resulted in posterior and nasal displacement of the leading haptic and optic toward the peripheral bag and posterior capsule (see the video below to watch the procedure).

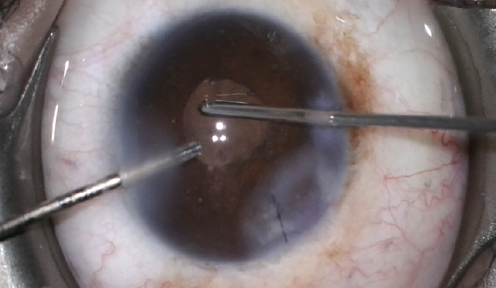

The lens appeared to center well with an OVD still in the eye, and the visualized portions of the posterior capsule seemed to be intact. Irrigation and aspiration were performed slowly, and care was taken to maintain pressurization of the anterior chamber (AC). Unfortunately, after the OVD was carefully removed, the lens exhibited subtle nasal and posterior tilt, and it was resistant to centration. No vitreous was noted in the AC, and this was confirmed with an injection of diluted triamcinolone. A dispersive OVD was injected behind the IOL and into the AC. The IOL was rotated into the AC, cut nearly in half with 19-gauge scissors, and then removed through the main wound (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A pair of 19-gauge scissors are used to nearly bisect the acrylic IOL while it is in the AC.

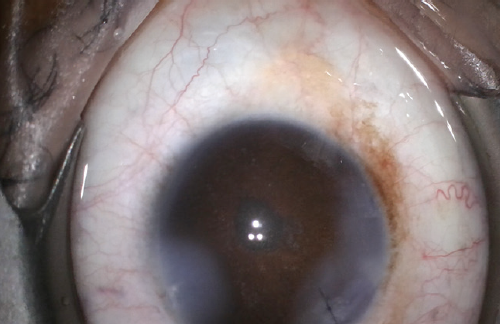

The sulcus and AC were refilled with a dispersive OVD followed by a cohesive OVD, and a three-piece lens was carefully inserted into the sulcus. The wound was sutured, and a thorough bimanual anterior vitrectomy was performed after a small strand of vitreous was noted nasally (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A bimanual anterior vitrectomy is performed after lens insertion because a nasal strand of vitreous was observed in the AC.

Diluted triamcinolone and carbachol intraocular solution (Miostat, Alcon) were instilled, and no vitreous was noted (Figure 4). The patient did well postoperatively and, thankfully, has not developed cystoid macular edema or other complications in the 2 years following surgery.

Figure 4. Round pupil at the end of the case.

Figures 1–4 courtesy of Kourtney Houser, MD

CONCLUSION

This case stays with me as a reminder of the importance of unwavering attention, even when the most challenging portion of a case appears to be over. By remaining alert, we surgeons are better equipped to manage complications, regardless of when they occur during a case.

Pearls for Managing Complications

Tuba S. Mirza, MS, and Eric D. Rosenberg, DO, MScEng

Letting your guard down toward the end of a perfect case may have undesirable consequences. When a complication occurs in this situation, the ability to stay calm, assess the situation, quickly correct the problem, and humbly proceed is what makes a good surgeon great. It is how ophthalmic surgeons deal with these rare instances that defines their true success.

The inevitable

Posterior capsular rupture (PCR) is an inevitable occurrence in every cataract surgeon’s career. PCRs may occur at any stage of surgery but are most common during the removal of nuclear material when the capsule is the most exposed and vulnerable to the phaco process. The key steps to preventing further complications in the event of a PCR are outlined in the accompanying sidebar.1

PCR: Preventing Further Complications

Key steps that can prevent further complications when a posterior capsular rupture is identified.

- Early recognition

- Regained control

- Stabilization of the chamber

- Prevention of further enlargement of the rupture

- Removal of the remaining lens fragments

- Refinement of the IOL position

- Close monitoring of the patient postoperatively

THE ZONULOPATH

A thorough preoperative history can help to identify certain conditions that can predispose an individual to zonular instability. Some cases, however, are discovered incidentally during surgery. It is crucial to recognize the early signs of zonulopathy and manage it effectively. Early recognition can allow you to prepare and plan for the case.

There are several options for addressing zonulopathy and stabilizing the capsular bag, including a standard capsular tension ring, a Cionni Capsular Tension Ring (Morcher), an Ahmed Segment (Morcher), standard capsular tension hooks, and a glued capsular tension hook technique.2-4 The best approach in a given situation depends in part on the degree of zonular loss.2-4 If zonulopathy is present, an overly aggressive vacuum setting can spin the IOL and tear the bag. Lowering the vacuum and aspiration settings can reduce zonular stress. Similarly, extending the zonular dehiscence by erroneously positioning the aspirating port toward the weak zone can further complicate surgery.

THE UNWITNESSED

Retained lens material. Lens material retained in the posterior or anterior segment may trigger inflammation in the postoperative period.5 It is important to remove nuclear and cortical material as completely as possible. If stubborn cortical adhesions are encountered during surgery, placing the IOL and gently rotating it toward the area of concern to protect the bag and then performing targeted aspiration can assist with nuclear removal.6

Residual lens material in the anterior segment may be monitored, medically treated, or surgically removed. A small amount of cortical material can be broken into smaller pieces by an Nd:YAG laser for faster dissolution by the inflammatory process.7 If a sizeable amount of retained cortical or nuclear material is noted postoperatively, a return to the OR to remove it may be the best way to avoid further complications such as cystoid macular edema, corneal edema, and corneal decompensation.5,7 Lens material that has migrated into the posterior segment may require management by a vitreoretinal specialist depending on its extent and the postoperative outcome.

Retained OVD. The use of a high flow rate and high vacuum can aid in achieving complete removal of an OVD. Using viscocohesive agents in lieu of viscodispersive agents can make this step quicker and safer. Gently rocking the IOL and placing the I/A tip underneath it may remove a residual amount of an OVD, but being too aggressive with the I/A tip can rupture the capsular bag.

Patients with a retained OVD may initially present with a postoperative pressure spike.

THE IMPLANT

A decentered IOL, particularly an accommodating design, can ruin the most beautifully executed cataract procedure. Injecting the wrong IOL or positioning it incorrectly is problematic as well. An upside-down IOL (S-shape vs Z-shape configuration) noted during the surgery should be repositioned and flipped at that time. Depending on the IOL—and your level of experience—there are several options for management, including lens recentration, an IOL exchange, insertion of a piggyback lens, and corneal refractive surgery.8

THE “HOW’D THAT HAPPEN?”

Sometimes surgery proceeds like clockwork, and even a postoperative review of the video does not reveal why things went wrong (see the video below to watch such a case).

Preparing the OR in advance with the proper equipment, capsular support devices, and backup lenses will allow you to overcome most unexpected occurrences during surgery. The main factors that prevent further complications are your ability to remain hypervigilant, confident, and calm and to resist the natural instinct to immediately remove instruments from the eye. Early recognition of a problem, stabilization of the chamber, use of appropriate devices at the correct times, and avoidance of AC collapse can help to avoid vitreous prolapse and the need for an anterior vitrectomy.

1. Chakrabarti A, Nazm N. Posterior capsular rent: prevention and management. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65(12):1359-1369.

2. Jacob S, Agarwal A, Agarwal A, Agarwal A, Narasimhan S, Kumar DA. Glued capsular hook: technique for fibrin glue-assisted sutureless transscleral fixation of the capsular bag in subluxated cataracts and intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40(12):1958-1965.

3. Cionni RJ, Osher RH. Management of profound zonular dialysis or weakness with a new endocapsular ring designed for scleral fixation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1998;24(10):1299-1306.

4. Hasanee K, Ahmed KII. Capsular tension rings: update on endocapsular support devices. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2006;19:507-519.

5. Zavodni ZJ, Meyer JJ, Kim T. Clinical features and outcomes of retained lens fragments in the anterior chamber after phacoemulsification. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(6):1171-1175.

6. Han KE, Han SH, Lim D, Shin MC. A modified-simple technique of removing the lens cortex during cataract surgery. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65(1):59-61.

7. Hood CT, Shtein RM, Mian SI, Sugar A. Neodymium-yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser lysis of retained cortex after phacoemulsification cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(5):808-813.e1.

8. Rongé LJ. Human error during cataract surgery: right patient, wrong lens. EyeNet Magazine. Accessed June 10, 2021. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/human-error-during-cataract-surgery-right-patient-w

What Lies Beneath: Spontaneous Hyphema After Irrigation and Aspiration

John X.H. Wong, FRCOphth

A 73-year-old patient was scheduled for phacoemulsification and IOL implantation in the right eye. The patient had no significant medical history and was highly myopic bilaterally (-8.00 D; axial length, 26.60 mm). The preoperative examination revealed bilateral 3+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts, 1+ posterior subcapsular cataracts, and well-dilating pupils. No other abnormalities were noted in the anterior segment or retina. This surgery was the last case on my schedule for the day, and all preceding cases were uneventful. I was feeling confident that I would successfully finish my surgical list.

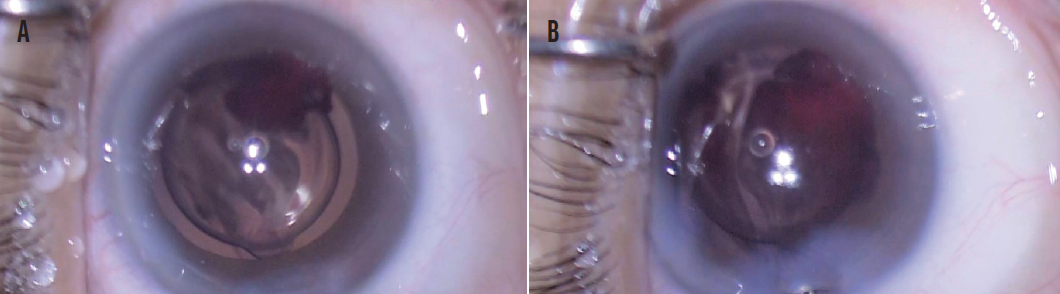

This case proceeded swiftly and uneventfully until I removed the I/A probe from the eye after completing aspiration of the OVD. A significant amount of blood emanated from under the nasal clock hours of the iris (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Blood gushed from under the nasal iris when the I/A probe was removed (A). Hyphema recurred after the AC was tamponaded with an OVD for 90 seconds (B).

The surgical incisions were immediately hydrated, and the AC was filled with the remainder of the OVD. The eye was maintained in this state for 90 seconds. Upon removal of the I/A probe after aspiration of the OVD, however, the hyphema recurred (Figure 5B). A small aliquot of preservative-free phenylephrine 2.5% (diluted in 3 mL of balanced salt solution) was injected intracamerally. The I/A probe was reintroduced into the AC with the bottle height set to maximum. The bottle height was gradually lowered over 3 minutes. A small amount of blood oozed from under the iris when the I/A probe was finally removed from the AC.

The patient was discharged with a prescription for prednisolone acetate 1% and levofloxacin 0.5%, both administered hourly, and oral acetazolamide 250 mg administered three times daily. A sliver of hyphema was noted on postoperative day 1. A workup of the patient was performed for possible causes of the bleed. The patient had no history of uveitis, and therefore the hyphema was unlikely to be the Amsler sign. She had no clotting/coagulation disorders (not found on antiplatelets/anticoagulation and platelet count/coagulation profile normal). Anterior segment imaging was performed to exclude iris lesions such as a tumor.

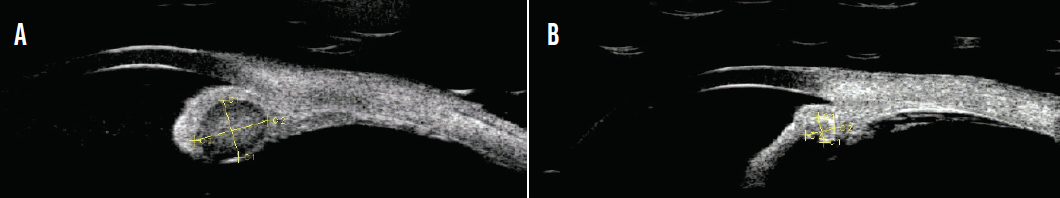

Figure 6. UBM images of the posterior iris cystic lesion 1 day (A) and 1 month (B) after surgery.

Figures courtesy of John X.H. Wong, FRCOphth

Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) detected a 2.08 x 1.67-mm posterior iris cystic lesion (Figure 6A). Excision biopsy of the lesion was offered repeatedly, but the patient was adamantly opposed to further surgery and even accepted the risk of a malignant tumor of the iris. Serial UBM scans showed shrinkage of the cystic lesion (Figure 6B). This was accompanied by a gradual but complete resolution of microscopic hyphema noted at postoperative month 1. Uncorrected distance visual acuity was 20/30 in the operated eye, and the posterior iris lesion is being monitored.