A white cataract on a surgeon’s schedule always brings a bit of uncertainty to the OR flow. Will the dreaded Argentinean flag sign (an uncontrolled split of a trypan blue-stained anterior capsule) complicate the case?

CASE IN POINT

The First Eye

A 35-year-old woman with poorly controlled diabetes presented with rapid-onset blurry vision in both eyes. The examination was consistent with a light-perception white cataract in the right eye and a 5+ cortical cataract, almost completely white, in the left eye.

AT A GLANCE

• Intumescent white cataracts are unpredictable and pose a risk of capsular radialization.

• By using best-practice preventive measures and/or proper and careful postradialization techniques, surgeons can achieve a successful outcome.

• A femtosecond laser can be an asset in these cases, but this approach is not foolproof.

Not all white cataracts are intumescent or at increased risk of anterior capsular radialization, but I find that those in younger patients and those with a rapid onset present the highest risk. Nevertheless, careful surgical management should be applied to all white cataracts.

MANAGING A CASE AFTER THE ARGENTINEAN FLAG SIGN

• Create two semicircular capsulotomies within the remaining anterior capsule, the initiation with a microscissors or cystotome needle.

• Use low-flow irrigation/aspiration or phaco settings to remove the soft lenticular contents.

• Inject viscoelastic, via the sideport incision, to maintain the anterior chamber, and avoid “trampolining” and extension of the capsule when withdrawing the phaco tip or I/A cannula from the eye.

• Choose a three-piece acrylic IOL that permits in-the-bag or sulcus placement. A three-piece IOL also permits more advanced fixation such as iris-sutured or intrascleral haptic fixation if they become necessary.

The advent of femtosecond laser technology allows surgeons to automate the capsulotomy and treat white cataracts in a closed, pressurized anterior chamber environment. I use the laser for white cataracts when possible. It is important to note, however, that incomplete laser capsulotomies are possible with an intumescent lens.1 The case described in this article is from a few years ago, before laser technology for cataract surgery was available.

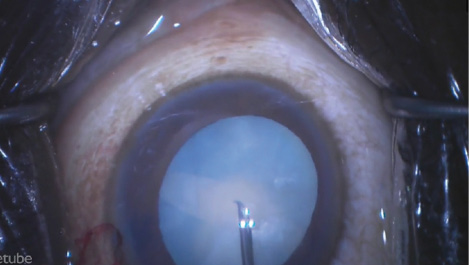

Operating on the patient’s first eye, I filled the anterior chamber with a dispersive viscoelastic and ensured a flattening of the lens dome. As soon as I punctured the capsule with a cystotome, however, I encountered the fastest Argentinean flag sign I have ever seen (Figure 1). I quickly transitioned to damage-control mode.

Figure 1. The Argentinean flag sign can occur despite flattening of the lens dome with viscoelastic.

Using the steps outlined in the sidebar Managing a Case After the Argentinean Flag Sign, I completed the case and achieved an excellent outcome, despite the capsular radialization.

The Second Eye

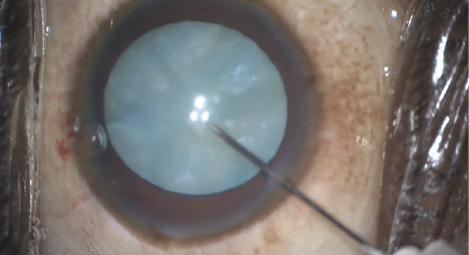

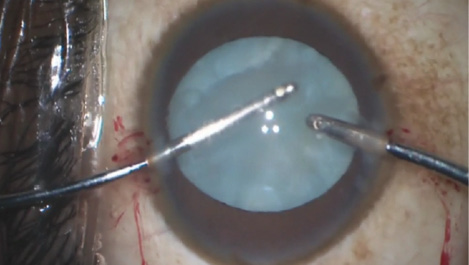

After an unanticipated delay, the patient returned with a similar white cataract in the fellow left eye. Knowing the lens was intumescent, I employed every available countermeasure (Figures 2 and 3; see Preventing an Argentinean Flag Sign). Importantly, despite apparent decompression of the lens, deeper pockets of liquefied cortex maintained intralenticular pressure and the tendency towards radialization throughout the capsulorhexis. I used the Little tear-out rescue technique to manage the situation (see video below).2

Figure 2. A needle held on a syringe can initiate the capsulotomy via a watertight paracentesis.

Figure 3. The surgeon uses split irrigation/aspiration to remove the liquefied “lens milk” and to enhance visualization prior to continuation of the capsulotomy.

Tal Raviv, MD, performs cataract surgery on this patient’s two eyes.

CONCLUSION

Intumescent white cataracts are unpredictable and pose a risk of capsular radialization. By using best-practice preventive measures and/or proper and careful postradialization techniques, surgeons can achieve a successful outcome.

PREVENTING AN ARGENTINEAN FLAG SIGN

• Pressurize the anterior chamber at all stages of capsulotomy creation with a dispersive viscoelastic (ie, pressure of approximately 30 mm Hg).

• Initiate puncture of the central capsule with a 26- or 30-gauge needle through a watertight paracentesis.

• Manually aspirate expressed liquefied cortex using a syringe attached to the needle.

• Perform small-incision split irrigation/aspiration via watertight incisions to further decompress liquefied cortex and maintain good visualization. Then, reinflate the anterior chamber with viscoelastic.

• Be prepared for radialization caused by other pockets of liquefied cortex that are exerting pressure, even with apparent deturgescence of lens.

• Convert to the Little capsulorhexis tear-out rescue technique1 at the start of any capsular radialization by unfolding the leading capsular flap and then pulling backward to redirect the tear centrally. Sometimes, alternating between traditional capsular tearing and the Little technique multiple times will allow completion of a continuous capsulorhexis.

1. Little BC, Smith JH, Packer M. Little capsulorhexis tear-out rescue. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:1420-1422.

The femtosecond laser can be an asset in these cases. This approach is not foolproof, however, so surgeons must be prepared to use the manual steps outlined in the sidebars. New devices are in development to help surgeons perform complete capsulotomies in these most challenging cases such as CapsuLaser (CapsuLaser) and ApertureCTC (International Biomedical Devices) in addition to the now FDA-cleared Zepto Capsulotomy System (Mynosys Cellular Devices).3-6

1. Conrad-Hengerer I, Hengerer FH et al. Femtosecond laser–assisted cataract surgery in intumescent white cataracts. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40(1):44-50

2. Little BC, Smith JH, Packer M. Little capsulorhexis tear-out rescue. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:1420-1422.

3. Packard R. A new approach to laser capsulotomy. CRSTEurope. October 2015. http://for.tn/1xis3YF. Accessed May 26, 2017.

4. Kontos MA. Integrating precision-pulse technology in capsulotomy creation. CRSTEurope. October 2015. http://bit.ly/2roV7GN. Accessed May 26, 2017.

5. Ben-Nun J. A simple solution for the complex problem of capsulorrhexis creation. CRSTEurope. February 2016. http://bit.ly/2qn0WjR. Accessed May 26, 2017.

6. Brennan K. Making the cut: capsulotomy devices. Review of Ophthalmology. May 10, 2017. http://bit.ly/2r5p79X. Accessed May 26, 2017.