I returned from last year's American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) annual meeting in Chicago concerned about the common theme I heard: ophthalmologists hate electronic health records (EHRs). The distaste for EHRs is understandable because they are associated with a decline in productivity, an increase in costs in terms of hardware and staff, an inability to find what is needed when it is needed, and an intrusion of keyboards between providers and patients. My staff and I have integrated EHRs into our flow, and we do not have the aforementioned problems. In fact, we have been able to enhance our efficiency and productivity by making EHRs work for us rather than against us.

The EHR system is now a part of ophthalmologists' professional lives. When we see patients, we must get the required examination information into the medical record, but concentrating efforts on the record and ignoring the nature and flow of the visit are the fundamental problems. EHR software engineers demonstrated this issue to me years ago during a visit to our office. When they observed our use of the system, we heard comments like, “I had no idea about that” or “Maybe we should look at redesigning that function.” No wonder I wanted to dropkick the whole thing out the second-story window.

TODAY

At our multiphysician practice, we have used an EHR system since January 2000. We have learned a great deal about EHRs and have suffered through the problems my colleagues complained about at the AAO meeting. We received our Meaningful Use Stage 1 payments in 2012 and 2013 and completed a Meaningful Use Stage 2 submission for the last quarter of 2014. We have also been early participants in the AAO Intelligent Research in Sight (IRIS) Registry Program. By sharing some of our experiences, I hope that this article will help you improve your day-to-day clinical flow.

The problem is not with the software but rather with system integration. Practices need to use EHRs to mirror, replace, and improve the functions that used to take place in the paper chart. Too many allow the EHR system to dictate office flow instead of ensuring that the physician controls the pace of clinic days while using EHRs to document the clinical findings.

Software engineers rarely understand the flow of a busy ophthalmology practice, nor do they know how the clinic wants the documentation to work. The software is likely not the problem. In fact, ongoing updates, consolidation, continued regulatory oversight, IRIS, and Meaningful Use will drive the quality and the similarity of the different software systems even closer together.

HOW IT WAS: THE BEAUTIFULLY EFFICIENT PAPER CHART

Physicians and their staff grossly underestimated the sophistication of the paper chart. It was “engineered” to allow the entry, retrieval, and communication of large amounts of pertinent data in an efficient manner. Certain data were entered in the same place every time. Practices used color-coding as alerts to a special problem—a complicated series of tabs in the back of the chart for operative reports, photographs, fields, letters, etc. The chart served to record/communicate to the next user the events that took place.

How Did We Used To Do That?

Before EHRs, our clinic and most clinics around the country had a routine something like this:

The technician took the patient back, wrote down the history, checked his or her visual acuity and IOP, performed the required tests, dilated the pupils, and put the chart up for viewing. When the patient was ready, the physician was somehow notified.

The provider grabbed the chart and either refreshed his or her memory about the returning patient or read up on the new patient, reviewed the pertinent data, and committed pieces of data to memory to create an image of the patient.

The chart was put aside. The eye care practitioner entered the room and greeted the patient with a handshake with no screen or keyboard between them. On occasion, the physician would check the chart for additional information but most times would complete the examination without the chart's coming between him or her and the patient.

The doctor moved back and forth from one scribe room to the other for the entire clinic session.

How It Can Be: a Return to Efficient Flow

The key is to take each and every step of the paper chart visit and create the comparable function with an EHR system like this:

The technician takes the patient back and enters the history, visual acuity, IOP, etc., into the EHR. The requested testing is performed and its results entered into the patient archive/database. The pupil is dilated, and the information is saved in the EHR system.

To reproduce the chart review, we use a standup, password- protected monitor outside one of the scribe rooms. The monitor is out of patients' line of sight and complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The doctor clicks through the workup that the technician has entered and mentally notes pertinent findings. If the doctor needs to look at images or test results, he or she will click in the taskbar on the icon for the image management software (the technician has already loaded the patient and examinations) and review the information, again, taking the mental notes to complete that patient's visit profile. When the doctor has accumulated all the pertinent data needed for that patient, he or she will click out of that patient's record and enter the examination room.

The scribe follows the doctor into the room and enters the dictated examination findings, diagnosis, plan, and charge data in real time. We use scribes, but we used them with paper charts, too. For the completion of the visit, most of the assessments and plans in the EHR system are in macro formats and/or drop-downs for rapid entry into the patient encounter.

Another technician/scribe pulls up the next patient's EHR, and the doctor moves back and forth from one scribe room to the other for the entire clinic session.

On an operational/technical point, we decided to keep our tests such as optical coherence tomography, visual fields, topography, photographs, etc., out of the EHR system and store them in a separate database. We store one copy of the test on the device and one in the image management software database. (We use Zeiss Forum [Carl Zeiss Meditec], but there are several others.) We keep these tests/images in the taskbar and open them to review before we see the patient.

HOW THIS CAN WORK IN YOUR OFFICE

Our doctors rarely if ever interact with the EHR system in the examination room. Our practice has used a fully integrated EHR system since January 2000. It is safe to say that we have made every conceivable mistake that one can make with EHRs, electronic scheduling, and practice management software.

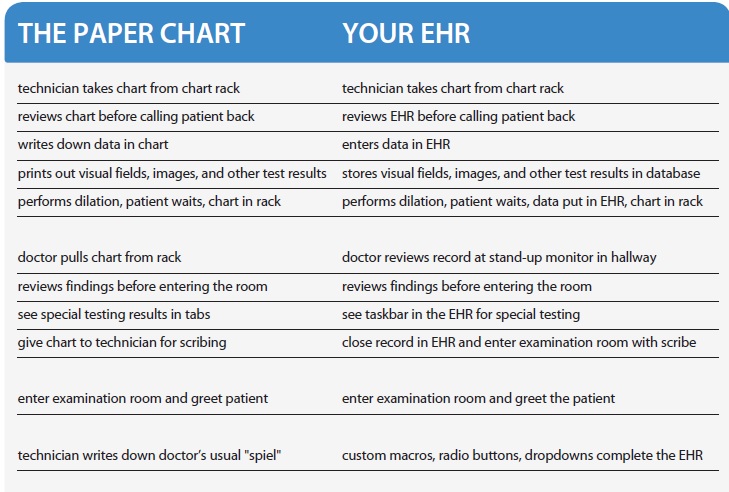

Begin by setting up a two-column spreadsheet or table with the columns side by side (see graphic on previous page). One column heading is the paper chart, and the other is an EHR. Have an experienced technician walk through a visit with a mock patient using the paper chart. Another technician and the doctor will observe and write down every step until the patient has gone all the way through to checkout. Then, in the other column, go through your EHR, and identify the comparable step on the EHR side that mimics your paper chart method and patient flow.

This will allow you to create a working flow document that you can try in the clinic. The process will not go smoothly at first. It will take several months before the clinic flow improves. Keep fine-tuning the process until the two types of visits are as close to each other as possible. When you are in an EHR, always ask yourself, “How did we do that with paper?”

CONCLUSION

I would suggest that the patient flow and productivity that you enjoyed with paper charts are obtainable with EHRs. The objective is to get the doctor away from the screens, away from the keyboard, and back to the patient. The steps outlined herein are not a magic formula but simply a way to look at how things used to work and replicate that system using EHR software. Although in my practice, our doctors use EHRs to review patients' examination findings and special testing, we are rarely found typing/entering/”box checking,” which frees us to see more patients and enjoy our day in the clinic. This end result is a product of thinking about our clinic flow as a systems problem rather than an EHR software problem and working to apply the best workflow to the EHR software. n

Edward L. Colloton, MD

• Eye Surgical Associates in Bloomington, Illinois

• (309) 662-7700; ecolloton@gmail.com

• financial interest: none acknowledged