Endotoxin is a possible cause of toxic anterior segment syndrome (TASS).1,2 Bacterial endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is produced by gram-negative bacteria and is a potent inflammatory mediator that causes septic shock syndrome. The Lipid A portion of the LPS molecule is thought to be responsible for this potent inflammatory effect. Endotoxin is heat stable and can readily survive short-cycle sterilization.3 Endotoxins are also recognized as an important cause of diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK) and have been identified in the steam distillate of the Statim sterilizers (Scican Inc., Pittsburgh, PA).4 Thus, although bacteria such as Pseudomonas are killed by short-cycle sterilization (3.5 minutes at 180°C), their endotoxins are released from the cells' walls in the sterilizer. These endotoxins remain biologically active and can be deposited on instruments used in anterior segment cataract surgery.

Previous outbreaks of TASS have also been linked to the contamination of the ultrasonic baths with similar bacteria5 and to the liquid detergent used in the cleaning bath.1 Our recent experience with an outbreak showed an association between the contamination of an autoclave reservoir with gram-negative, endotoxin-producing bacteria and TASS.6

OUTBREAK INVESTIGATED

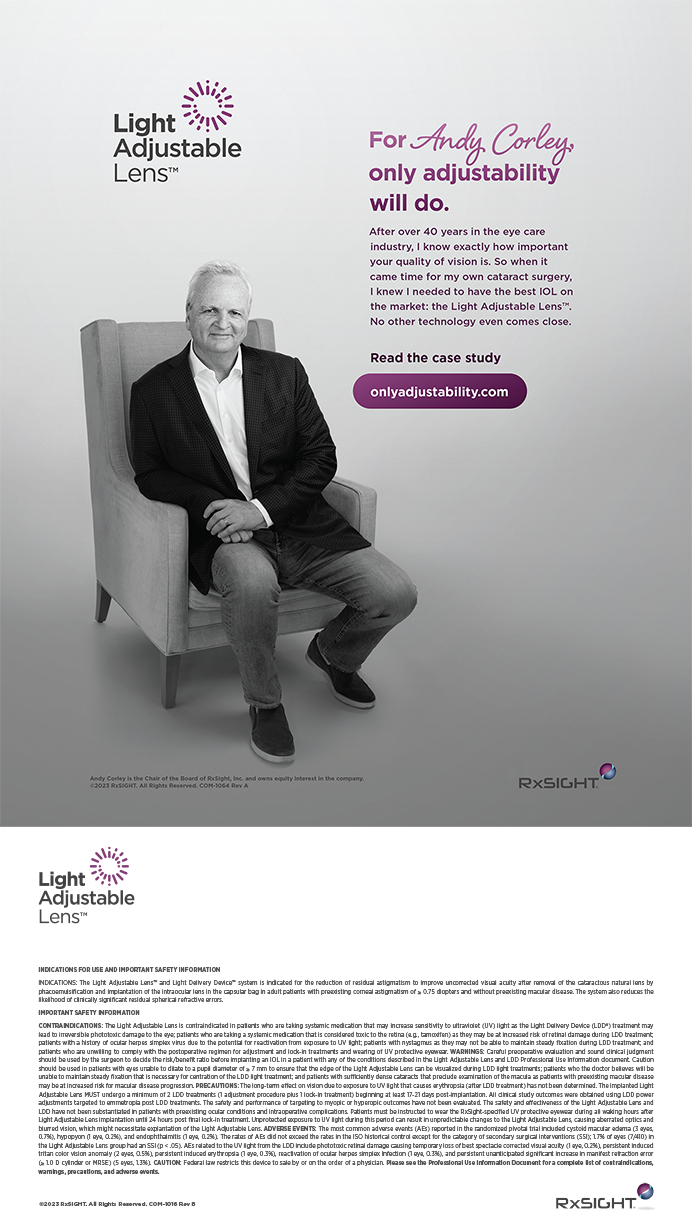

Our hospital experienced an outbreak of TASS that began with four cases occurring during a 3-week period. After it investigated the incident, the only suggestion to control the outbreak from the hospital's infection control department was for surgeons to switch from multi- to single-use phaco tips. This change in protocol proved ineffective in preventing further cases of TASS (Figure 1). The method of sterilization ophthalmologists in the hospital used was a combination of a short cycle with the Statim sterilizers and a prolonged-cycle system with sterilizers from the hospital's central sterile department. Culturing of the Statim sterilizers showed a heavy growth of gram-negative bacteria (predominantly Sphingomonas, Ralstonia, and Pseudomonas), but no additional action was taken based on these results at that time.

Another cluster of 10 TASS cases occurred between months 13 and 17 of the reported outbreak. Surgeons limited their use of short-cycle sterilization and replaced reusable with disposable cannulas. Although these steps proved partially effective, the outbreak continued. Further bacterial cultures and biofilm sampling of the Statim sterilizer reservoirs showed the same bacteria and associated biofilms within the reservoirs (Figure 2).

Our hospital replaced its three Statim sterilizers and instituted a rigorous cleaning protocol for the new units that included emptying them daily, cleaning their reservoirs with a quaternary ammonium compound daily, and periodically replacing their inner tubing. The sterilizers had been in use for more than 8 years and had never been serviced or cleaned. Following these interventions, the outbreak ceased, and no further cases have been reported at the hospital in the 2 years since.

PROTOCOLS FOR THE MAINTENANCE OF A STERILIZER'S RESERVOIR

We have found the following protocols effective in controlling biofilm and the contamination of sterilizers' reservoirs with bacterial endotoxin. These procedures are not approved by the sterilizers' manufacturers or the FDA. Maintenance based on the endotoxin theory has thus far proven successful against outbreaks of both TASS and DLK.3,6 We recommend appropriately cleaning reservoirs to clinics experiencing cases of TASS.

During periods without a case of TASS, a clinic's staff should perform routine maintenance of the sterilizer on each surgical day (see Routine Maintenance for a Sterilizer). The unit's inner tubing should be replaced monthly.

During an outbreak of TASS or DLK, the sterilizer may become contaminated (see Protocol for the Duration of an Outbreak). Modified protocols may be necessary based on the severity of the outbreak as well as the nature of the bacterial biofilm identified. Although most biofilm produced by bacteria is inactivated by 70 alcohol, we have found a difference in the substance's susceptibility to various biocides depending on the specific bacteria.7 During confirmed outbreaks, household bleach (sodium hypochlorite) diluted in distilled water may be substituted for 70 alcohol. We recommend seeking further advice from those with experience such as ourselves before using hypochlorite 0.525 (ie, commercial household bleach 5.25 diluted 1:10 with water) due to the potential for damaging the sterilizer's lining and tubes. Our use of this solution in specific outbreaks was based on our assessment of the resistance of involved bacterial biofilm to the biocidal agents that are more easily employed (ie, 70 alcohol).

CONCLUSION

Short-cycle, steam-generating, tabletop sterilizers such as the Statim have proven to be efficient in high-volume cataract surgical centers due to their simplicity of use, rapid cycles, cassette-based system, reliability, and economy. Most units use a sterilization time of 3.5 minutes and a total sterilization cycle time of 6 minutes compared with the 45-minute cycles of standard sterilizers. Short-cycle sterilizers are not without their problems, however. One major disadvantage is their inability to deactivate bacterial endotoxin, which can be found in the steam distillate.4 This drawback creates the potential for the toxic material to be deposited on "sterilized" instruments. Bacterial endotoxin (LPS) is a potent initiator of inflammation; very low levels can incite significant inflammation. Fortunately, relatively simple measures of sterilizer maintenance, although not approved by the manufacturers, have proven highly effective at reducing bacterial biofilm, the typical source of endotoxin in short-cycle sterilization systems.

Because TASS is multifactorial, it is often difficult to determine if one or more causes are involved. We have investigated two recent outbreaks in which autoclave contamination appeared to have an important role. Other factors such as the incomplete cleaning of ultrasonic baths5 and inadequate rinsing of the lumens of reusable cannulas and phaco tips have a greater potential to incite TASS if short-cycle sterilizers are used because of their inability to deactivate endotoxins.

Simon Holland, MB, FRCSC, serves in the Department of Ophthalmology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, and he is in private practice at Pacific Laser Eye Centre, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. He acknowledged no financial interest in the products or companies mentioned herein. Dr. Holland may be reached at (604) 875-5850; simon_holland@telus.net.

Douglas Morck, DVM, PhD, practices in the Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, and Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. He acknowledged no financial interest in the products or companies mentioned herein. Dr. Morck may be reached at (403) 220-5278;dmorck@ucalgary.ca.