CASE PRESENTATION

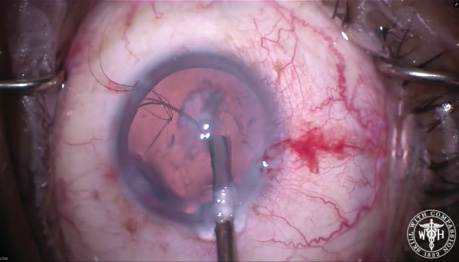

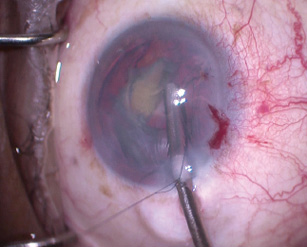

Figure 1. At the time of surgery, a dense 4+ nuclear sclerotic cataract and nonpharmacologically dilated pupil are evident.

—Case prepared by Brandon D. Ayres, MD.

THOMAS BOLAND, MD

This type of case will test all of your skills as a clinician and a surgeon. It appears that there is a widely dilated tonic pupil, and the presence of phacodonesis guarantees that there will be zonular instability as well. Given the patient’s progressive glare and decreasing visual acuity, the time for surgical intervention is now.

Extensive preoperative counseling would be required regarding the difficulty of surgery, and no promises should be made regarding a reduction in glare, because it may be difficult to mobilize iris tissue this many years after the patient’s injury. My surgical plan and informed consent would include cataract extraction with the implantation of a posterior chamber IOL and pupilloplasty by cerclage.

My initial approach would be through a temporal clear corneal incision, followed by an injection of a dispersive viscoelastic for chamber stability. Three separate paracentesis incisions would be placed equally spaced around the limbus. Next, I would perform the continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, while paying attention to the stability of the capsule and looking for areas of zonular loss or instability. I would have capsule hooks on standby in case the capsular instability were severe.

I would perform extensive hydrodissection followed by hydrodelineation, while taking care to minimize rotational forces as much as possible. The lens nucleus could then be disassembled; I prefer to bisect the nucleus and elevate the heminuclear segments above the capsular plane, with no rotation of the lens required. I would be prepared to place a capsular tension ring (CTR) as soon as necessary but would wait to do so for as long as possible. Cortical removal using tangential stripping would minimize further zonular damage. After removing the cortex, I would inflate the capsular bag with viscoelastic and place the CTR. My preference in this case would be a three-piece silicone IOL, because I find that this type of lens often incites anterior capsular fibrosis and opacification, which could form an artificial pupil in the event that I could not sufficiently mobilize the iris tissue.

With the CTR and IOL in the capsular bag, I would remove viscoelastic from behind the IOL and place additional dispersive viscoelastic in the anterior chamber for greater chamber stability. I could then use micrograsping forceps through the main corneal incision and the paracenteses to determine the degree of iris tissue that I could use to place a suture cerclage. Even many years after injury, the iris tissue should still possess some elasticity, and it is likely that the pupillary margin can be gently stretched to cover the edge of the optic. A 10–O Prolene suture on a curved CIF-4 needle (Ethicon) could then be used along with micrograsping forceps to complete the pupilloplasty, with a targeted final pupillary size of approximately 4 to 5 mm.

GARRY P. CONDON, MD

I often consider cases such as this one challenging and lengthy enough to warrant deferring the added complexity of a big pupilloplasty procedure until later.

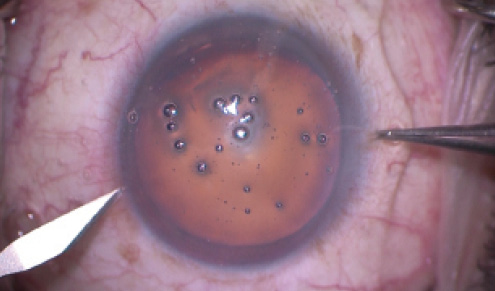

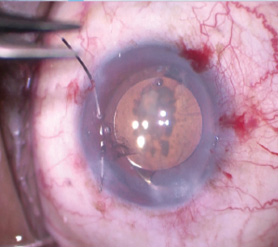

Figure 2. In a separate case, an Ahmed CTS held by an inverted iris hook supports a broad area of capsule.

(Courtesy of Garry P. Condon, MD.)

In this patient, the crystalline lens appears to be well centered, but the history of trauma and the phacodonesis suggest some degree of zonular instability. Traumatic angle recession can create a smaller circumference of zonular insertion, resulting in diffuse laxity. Capsule retractors in conjunction with a simple CTR might be sufficient to produce a good outcome here. There might be a broad zone of zonular loss, however, where an Ahmed Capsular Tension Segment (CTS; Morcher; US distributor FCI Ophthalmics) preloaded with a Gore-Tex suture (W.L. Gore & Associates) temporarily held in place with an iris hook could act as a supporting device during phacoemulsification (Figure 2). Whether or not the CTS needs to be permanently sutured could be determined later.

My preference would be to start with three broad-tipped capsule retractors like those manufactured by MicroSurgical Technology prior to phacoemulsification so as to stabilize the capsule and reduce posterior capsular mobility. Injecting a dispersive viscoelastic into the equatorial portion of the capsular bag midway and late in the phaco process would add support and place tension on the capsular bag as the lenticular material was removed. I would prefer to implant a standard CTR after removing cortex and relaxing retractor tension. I would insert the IOL in the bag after removing the retractors. Regardless of my initial expectations, I would be prepared to perform scleral fixation with two CTSs or a multieyelet Cionni Ring for Scleral Fixation (Morcher; US distributor FCI Ophthalmics).

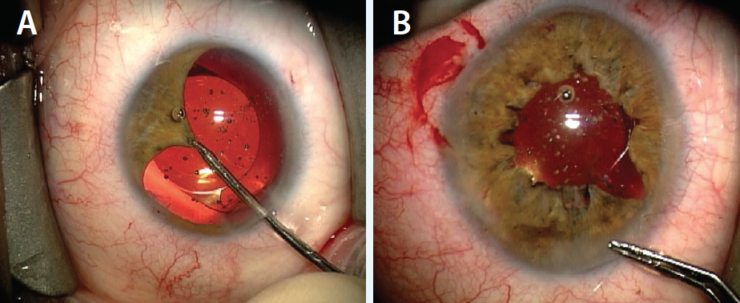

Figure 3. In another eye, pulling the pupillary margin centrally reveals the iris tissue available for repair 5 decades after blunt trauma (A). Dr. Condon ties the continuous cerclage suture (B).

(Courtesy of Garry P. Condon, MD.)

I prefer some capsular fibrosis and a chance to evaluate a patient’s response to cataract surgery before deciding on any pupillary surgery. All of the native iris tissue is present in this eye, and simply grasping the edge of the pupillary margin and bringing it centrally will reveal how amenable this atonic pupil will be to pupillary cerclage with a single or multiple-sector cerclage sutures (Figure 3). The degree of restorable function and cosmesis despite such dramatic mydriasis for decades can be remarkable.

ALAN S. CRANDALL, MD

This is an interesting problem, not common but also not rare. In this case, the indication for performing cataract surgery seems valid: a decrease in vision (improvement with pinhole) and significant glare, both leading to problems in the activities of daily life.

I would use trypan blue to stain the capsule; even though there is a good red reflex, it can be helpful to see the capsule’s edge if I need devices to stabilize the complex (Mackool Cataract Support System [Crestpoint Management] or capsule hooks [MicroSurgical Technology]). I would use a low-flow technique and minimize zonular stress via no or little rotation, tangential stripping of cortex, and the injection of viscoelastic before removing handpieces. I would use a CTR to stabilize the bag.

The other issue in this case regards iris management. One could consider iris cerclage, but with the pupil historically this large, the muscle and tissue may be so atrophic that the maneuver will be difficult to execute. I would therefore opt for an artificial iris, because I am involved in the FDA study. I would prefer the Artificial Iris (Dr. Schmidt Intraocularlinsen; distributed by HumanOptics; not FDA approved). This foldable silicone device can be placed in the bag (preferred) or attached to the sclera. The device’s color is matched to look like the native iris, and I find the result to be cosmetically exceptional. The other option would be the Iris Prosthetic System (Ophtec), which requires a Humanitarian Exemption through the FDA. Although this implant is not as cosmetic as the Artificial Iris, it significantly reduces glare and improves visual acuity.

WHAT I DID: BRANDON D. AYRES, MD

Laser cataract surgery was discussed, but the patient was resistant and wanted traditional cataract surgery. After a long conversation, he was scheduled for cataract removal with possible anterior vitrectomy and iris repair.

The primary concern was making a complete capsulorhexis. It was quite obvious from the stab with the cystotome that zonular support was poor. I completed the capsulorhexis but at a smaller-than-ideal size, adding to the challenge.

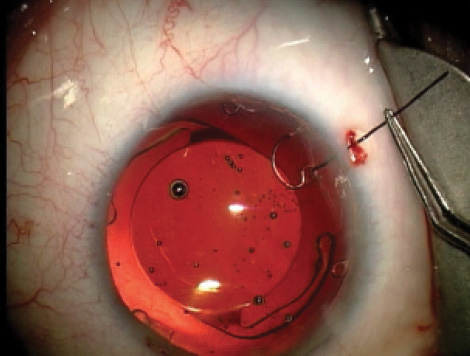

Figure 4. Dr. Ayres laces a 10–O nylon suture through the CTR’s leading eyelet. The suture allows him to control the CTR’s placement and ensures that the device can be recovered in the event of a complication with the capsular bag such as anterior or posterior capsular tears or complete zonular loss.

(Courtesy of Brandon D. Ayres, MD.)

Slow, controlled phacoemulsification allowed me to remove about 80% of the lens before the lack of zonular support necessitated placement of a 13-mm CTR. At this point in the surgery, I was not yet convinced that the zonules would support the capsular bag for the remainder of the surgery, so I laced a 10–O nylon suture through the eyelet of the CTR to ensure that the device could be easily recovered if all zonular support were lost (Figure 4).

Unfortunately, once the CTR was in the capsular bag, the gap at the ends of the device aligned perfectly with the area of zonular dehiscence, so I placed a second CTR to augment support. Thereafter, I removed the remaining lens fragments, performed careful cortical cleanup, and implanted a single-piece acrylic IOL.

Triamcinolone acetonide (Triesence; Alcon) helped me to identify vitreous that had prolapsed into the anterior chamber. I performed an anterior vitrectomy until I noted no vitreous in the anterior chamber and again filled the eye with viscoelastic.

Figure 5. Dr. Ayres uses 10–O Prolene on a CIF-4 needle to make a baseball-style suture along the pupillary border. After encircling 360º, the cerclage suture is tightened until the pupil reaches the desired size.

(Courtesy of Brandon D. Ayres, MD.)

Next, I used 10–O Prolene on a long, curved needle (CIF-4) to place a cerclage suture along the pupillary border (Figure 5). The knot was tied, allowing titration of the pupillary size to about 4 mm. Using intraocular scissors, I cut the Prolene knot short, after which I removed all viscoelastic from the eye and hydrated the incision.

One day after surgery, the patient’s UCVA had improved to 20/70 with minimal glare. By postoperative week 1, the UCVA had improved to 20/30, and the patient had no complaints of glare. Overall, he had an amazing recovery of vision, much better than expected. The patient was satisfied overall with the improvement in his vision and reduction of glare, but the last thing he said was, “It is still a little bit blurry. Will it get better?”

Editor’s note: use of the Prolene suture and CIF-4 needle is off label.